Two and a half years in southern Tunisia with the Peace Corps helped focus John Hartley even more. The program head in Tunis happened to be a registered architect, so Hartley's work with him qualified as an apprenticeship

Designs for Living

Wright, Emerson, and Native American traditions have influenced a local architect's home designs

B Y J O R D A N A D A I R

John Hartley builds houses. Sounds simple enough, doesn't it? You've seen it happening all over the Triangle: A developer brings in the surveyors, the back-hoes, the dump trucks, the cement trucks, and the crew that will frame and finish the structure. Down come the trees, out goes the dirt, and up goes the house--right? But for John Hartley, nothing could be further from the truth.

March 21, 2001

A R T S F E A T U R E

It's a beautiful, unseasonably warm day in February as I turn onto Johns Woods Road in Orange County and head up to Stone Knoll, one of Hartley's current developments. I pull up behind a nondescript white van. As I gather my pad and pen, a tall and sinewy man in his 50s, dressed in a pale red T-shirt, dungarees and faded white sneakers comes to greet me. Hartley has sharp blue eyes and a soft-spoken manner. Saying nothing, we walk together up the pathway to some stones on a grassy knoll just in front of the development, and take a seat at the edge. There's a light breeze, and slants of sunshine filter through the trees. In front of us stands a spiral of large stones and four monolithic slabs that were trucked, I soon learn, all the way from Tennessee: throwaways for the quarry, but totems for Hartley. He sets them up for me. To the East stands the Eagle and sunrise; to the South the Coyote and noontime; to the West the Bear and the setting sun; to the North the White Buffalo and old age. "This is sacred ground to me," he tells me, "an attempt to set aside and honor a part of the land that is the development."

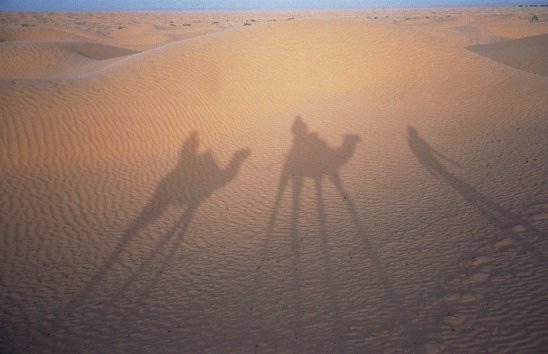

Photo By Alex Maness

John Hartley takes a medicine walk.

And therein lies the vision of this architect. In a profession where the focus is on tearing up the land and plopping down a building on the gouged-out space remaining, John Hartley is trying to send another signal.

It all begins with the land. When he thinks about the design for a house, Hartley works from the ground up, letting the lot determine the shape and space. Sometimes he takes a "medicine walk" (a Native American ritual that links the person to the landscape). Walking through the property, he reaches out and touches what speaks to him, seeking a spiritual connection that comes with knowing the land intimately. With the four cardinal directions of the "Medicine Wheel" as his guide, he tries to situate the house facing south on the lot, to create the greatest opportunity for the sun and the moon to filter into the space. "It is an organic architecture that is in tune with nature," he says. "The people who are living within the house are intimately aware of the outside environment through movement of the sunlight into the space, the phases of the moon. You never have to turn the weather on to see what's going on outside." And he tries to leave the landscape as undisturbed as possible--for as Frank Lloyd Wright believed, the house is literally created from the landscape of which it will soon be a part.

It all ends with the house. As you walk down the driveway, you are struck first by the sheer number of trees on the property. There are hundreds of them. You can barely see the house, but you know it's there. Finally, a shape appears. From the outside, you notice the odd angles, the geometrically shaped windows, the long sweeping porch, the symmetry between the parts, the light reflecting off the walls on the interior. You open the door, and walk through the entryway into an openness and a flood of sunlight. You look up to cathedral ceilings, and out across several rooms to the trees you just passed on your way in. As you move further into the room, skylights and oddly shaped picture windows combine to create reflected light in all directions. Something speaks to you in this house, but you can't quite put your finger on what it is.

John Hartley was born in Alabama, but grew up in Rockville, Md., the son of a secretary mother and cabinetmaker father. Fortuitously enough, his mother gave him a picture book of Frank Lloyd Wright houses when he was young. His mother was the most influential person in his early years, and he soon reveled in the artistic side she helped cultivate in him. This led him to Clemson University's school of architecture. "It was like going back to kindergarten," he recalls. "It was during that first year that I knew I wanted to be an architect."

What soon followed was a cross-country trip in a Volkswagon bus with a friend, where they hit as many of the Frank Lloyd Wright buildings as they could, soaking up the lines and space. They still arrived in San Francisco in time to spend the summer of 1968 going door to door, begging to do piecework with any architectural firm who'd have them. They spent that summer redesigning drive-in-movie parking lots: Anything for experience.

Photo By John Hartley

Where a Harley home is built, trees remain undisturbed.

On the way back home, they took in the southwest desert country, where Hartley found the inspiration of Wright once again in the subtle shading of color the sun created on the flat line of the landscape. Of equal importance was the connection he made with Native American traditions, the cosmology that undergirds his life today. He felt an intuitive connection to the symbolism of the Medicine Wheel, the ritual importance of the medicine walk, and the purification experience of the sweat lodge. During the years that followed, he internalized these beliefs, and used them to design and build houses that are in harmony with nature and spiritually satisfying to live in. As one of Hartley's influences, Ralph Waldo Emerson, wrote: "Every spirit builds itself a house; and beyond its house a world; and beyond its world a heaven. Know then, that the world exists for you: Build, therefore, your own world."

Two and a half years in southern Tunisia with the Peace Corps helped focus Hartley even more. The program head in Tunis happened to be a registered architect, so Hartley's work with him qualified as an apprenticeship. More importantly, though, he got to take his motorcycle out on holidays and ride the countryside taking in the sights and sounds of North Africa, where he discovered that simplicity and practicality worked when all you had to build with were the materials at hand. "So much of the indigenous architecture of the Mediterranean is based on forms that have been successful for thousands of years," he marvels. And he didn't find too many back-hoes or dump trucks out there. Natural forms--that's what he was looking for: simplicity and reverence and gratitude.

Once back in the United States, Hartley set about finding ways to build. First it was in Northern Virginia, building commuter communities to house the burgeoning population of Washington, D.C. in the early 1970s. The oil embargo soon put a stop to that, but he lucked into the gig of a lifetime when he worked on renovating townhouses in D.C. For a song, he could purchase the property, gut the insides, and then redesign and rebuild from scratch. It was just the hands-on experience he needed. Instead of designing what would never get built, he now got the chance to see his work come to fruition.

But the idealism that in part drove him to the Peace Corps still nagged at him. So he moved to North Carolina and went into business designing and building solar homes with a friend from his days in the Peace Corps. Getting in tune with the land, and using the tax credits that made the work practical, they built houses that just about anyone could afford. Eventually he set up his own company, headquartered on Carrboro's Weaver Street. At last, he was doing what he'd set his mind to years earlier--designing and building. Now he could put into practice the organic philosophy built from his study of Wright, his affinity for Emerson, and his grounding in Native American cosmology.

In keeping with his reverence for nature, Hartley says he strives to "bring as much of the outside world into the house as is possible." And walking through one of his houses, you sense immediately the innovative use of space (he believes that "space is cheaper than detail") and the inspired use of windows. Using the sharp angles he favors, and his aversion to creating boxes in his houses, Hartley shapes the open spaces within. He uses cathedral ceilings whenever he can, creates archways within the walls, and uses windows with geometric shapes (triangles, trapezoids, crescents, and rectangles). "The angled windows are like facets on a cut stone. They reflect more light in, and they give you more visual planes through which to look out," he explains. "So instead of having one view from a room you have several views, and it gives you the feeling of being wrapped around the outside world. It puts you out into the space rather than your looking out to it."

Photo By John Hartley

Harley brings outside elements indoors.

Hartley designs houses for the people who will live in them. Gail Sheridan, for one, is no ordinary client. A powerfully built and tough-talking woman, she brought her project to Hartley after little success with other architects. She liked what she'd seen of his other homes, but she also knew what she wanted in her own. What she needed was an architect who could work closely with her--"a single lady seeking safety and contentment"--and who would put their combined ideas into a design. She needed someone to help her get from room to room in her new house, someone who could sense the spiritual needs in a person and in a house. Sheridan found in John Hartley an "innovative and comfortable man who understands the way we live." Shortly after moving into her first Hartley house, she had to relocate to Atlanta. But she returned to Chapel Hill 18 months later and engaged Hartley's services once again. Two and a half years after moving out of her first Hartley home, Sheridan moved into her second one. For Hartley, no two houses are the same, even for the same client.

In his work today, Hartley sees around him constant reminders of the natural world's beauty, what he calls "the visual vitality of everything out there." These are reminders for him of the "connection with the spirit--visually and kinesthetically--I just know that I can feel the spirit in me." Native American beliefs have given him a spirituality and a profound sense of gratitude, all of which allows him, as he puts it, "to embrace the fullness of life"--and to design the houses that express those beliefs. EndBlock