A steady market presented itself in the person of Bob Leventry, a Chicagoan who had worked in Ecuador on various development projects for two years as a Peace Corps volunteer after retiring as president of a commercial insurance company

Activists of the air waves

ERPE was founded in 1962 by Leonidas Proano Villalba, a progressive priest who was called the ‘bishop of the poor’. Proano was an important member of the activist wing of the Catholic church that flourished in Latin America from the 1950s. In 1961, Proano visited the studios of Radio Suatenza, in the neighboring mountains of Colombia, where a fellow prelate and activist had pioneered using of the radio to teach literacy, mathematics, basic economy and political awareness. The largely illiterate and socially isolated indigenous Colombian groups that listened to Radio Suatenza were too widely dispersed to congregate in classrooms or meeting halls, and too busy to attend regular classes or organizational meetings.

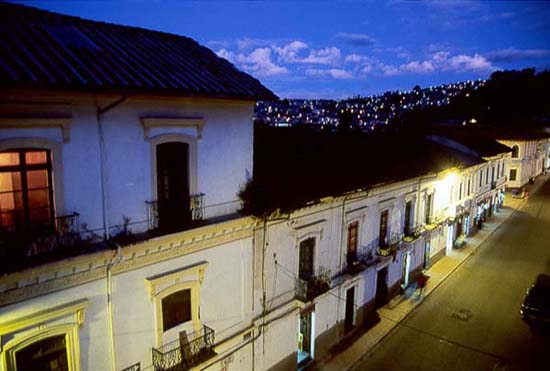

When he returned to the Ecuadorian Andes to begin his own broadcasts, Proano made literacy his first goal. ERPE equipped volunteer teachers from villages with a gas lamp, a makeshift blackboard, notebooks and a radio. Between 1962 and 1974, ERPE estimates, it taught 20,000 members of indigenous and mestizo groups in 13 Ecuadorian provinces how to read. As ERPE became a trusted friend to people who had never had any access to the media, let alone media directed to them, it expanded the range of its programming and the courses it offered. Subjects included all the ones Proano had seen at the Colombian station, and also instruction in more explicit social activism: how farmers could organize into cooperatives and get better prices for their crops, for example, or how villagers could fill out formal applications to the ministry of education to have schools built closer to their communities. ERPE used its handsome group of buildings in downtown Riobamba, which had been donated early in its life, to house in-depth courses. It was these courses, especially ones in leadership formation, that Juan Pérez followed most closely.

Juan himself became a leader. For seven years, he lived and worked at ERPE along with eight other students and the successor to Proano, an equally dedicated priest named Ruben Beloz. The young students wanted to take ERPE’s activist agenda even farther than did the original ERPE leadership, whom they thought of as being too content with the status quo. In 1988, the new generation took over, with the consent of the old. They elected Juan Pérez as their director.

Pérez faced the problem of how to raise money. There were no more subsidies from the Catholic church. ERPE had always derived a portion of its budget from its own enterprises, chiefly advertising sales at the radio station. ERPE had ended its legal affiliation with Catholicism in 1974, and separated completely in 1987. A Canadian fund for Ecuadorian development gave ERPE substantial support, and modest grants came from several European associations.

Organic farming looked like a way both to make some money and expand ERPE’s teaching mission. ERPE had once been deeded farmland near Riobamba, but had never made steady use of it. The farm went completely organic in 1991, after a year-long experiment. ERPE broadcast programs about organic farming and featured interviews with local farmers who had converted their farms. Pérez started offering courses in organic farming in buildings at the farm rather than in the city. “Indigenous people have to see what we are doing before they believe it”, he explains. From a few curious local farmers the first year, the number of annual visitors among ERPE’s listeners grew into the hundreds.

Many of these visitors were willing to think of taking up organic farming. But they needed on-site technical assistance. The two full-time ERPE farmers were too busy to act as traveling advisors, and the rest of the staff knew more about radio than farming. So Pérez hired agricultural tecnicos, or teachers, to visit farms, offer information and support, and provide organic seeds.

Return of a native crop

The question was which seeds to give to farmers. Pérez realized that he had only one chance to convert many of them, and it had to be with a crop that would produce immediate results. That eliminated the two main Incan agricultural triumphs: corn, which many of the farms nearby were too high to grow; and potatoes, which were too susceptible to blight to guarantee a high yield from organic seeds. That left three native plants: amaranth, the cereal high in protein and suited to high, dry climates; chocho, or Andean lupin, a high-protein bean useful for alternating with other crops; and quinoa, a potent symbol of the Spanish oppression of Incas.

Quinoa is unique among plants in offering a complete source of protein, one the World Health Organization has called equal to milk in protein quality. It is native to the Andean altiplano, the region that today includes Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador, which are still the world’s centers of quinoa, although it has been grown in the United States and Canada. Quinoa thrives at extremely high altitudes - over 3,000 meters or 10,000 feet - where frequently no other food crop will grow. For centuries the indigenous peoples of the Inca empire lived on quinoa, calling it their sacred mother grain and, as Rebecca Wood recounts in The Splendid Grain, waiting to plant it until their ruler ceremonially planted the first seed with a golden spade, his symbol of state.

The Spanish banned quinoa, perhaps fearing it as a source of Incan strength and certainly preferring to cultivate barley so that their invading armies could drink beer. Some of the banned crop did survive in the highest of the highlands, including the region around Riobamba, much of it 10,000 feet high. But even the indigenous and mestizo groups adopted the Spanish eating patterns of bread and rice, which they knew to mix with native beans, to improve the protein. By the early 1990s, few families farmed quinoa.

In all his organic thinking, Pérez had an enthusiastic and knowledgeable ally by his side, a young German named Hansjorg Gotz. He is a representative of BCS, a German organic certification board that has offices, and credibility, all over the world. Gotz’s predecessor had established the Ecuador base of BCS in a few extra offices at the hospitable ERPE headquarters. He was eager to help train the new ERPE teachers how best to farm organically.

The assistance the teachers offer is unpatronizing. Pérez says: “We try to work along with farmers in what they already know, to give them warm rather than cold instruction, that is acompañamiento, assistance, not lectures. We’re not professors teaching them their own business”.

If teachers are the occasional visitors, radio is the constant companion. Every day ERPE broadcasts a half-hour program on an organic farming technique - say, starting a worm farm to produce fertilized soil - and a teacher visiting a farmer in the field will go back over the points raised in the program. Teachers show farmers how to use a machine to thresh seed heads rather than the old way of beating them over a stone to make the quinoa seeds fall out. With a group of farmers they set a rotation schedule for tractors and threshers, and haul the machines from family to family.

A benign American invasion

This assistance and machinery doesn’t come free. Pérez needed someone to buy the quinoa he was convincing farmers to grow. A steady market presented itself in the person of Bob Leventry, a Chicagoan who had worked in Ecuador on various development projects for two years as a Peace Corps volunteer after retiring as president of a commercial insurance company. Leventry and his wife, Marjorie, became committed to Ecuador and in particular to organic farming there, and began looking for development projects they could continue on their own. In their searches, the Leventrys would frequently be disappointed to find that the packager who claimed to be organic and friendly to farmers would cheat. Bob says, “The government supported the use of chemicals and pesticides, and they still do”. He theorizes that government resistance to organic farming held back ERPE from finding local assistance for its nascent quinoa project.

Through other Peace Corps volunteers Leventry met Hans Gotz, and learned about the new ERPE quinoa: reliably organic, and certified by the internationally respected BCS, no less. He told Pérez that Inca Organics, the company the Leventrys formed with Marcos Tapia, their Ecuadorian partner during their Peace Corps service, would buy as much quinoa as the ERPE farmers could produce. Both the farmers and ERPE should go at their own pace, Bob said. Inca Organics would even pay for the harvest before planting time. This was just the kind of assistance Ecuadorian agencies had refused to give ERPE. And Leventry could trust Pérez to give the money straight to the farmers. ERPE and Inca Organics agreed that farmers would keep 30 percent of their harvest for their own use, even if that would delay profitability.

The bet paid off. In 1997, 220 families in 25 communities produced 27 metric tons of quinoa, “A heck of a start,” Bob Leventry says now. But it turned out to be a very modest beginning. Other families saw their neighbors make much more money from what they had been able to harvest on their small plots of land, usually less than one hectare, or two acres. Seeing is believing, and families joined by the hundred and then by the thousand. In 2001, 4,025 families produced 700 metric tons of quinoa, keeping 200 metric tons to feed themselves. ERPE has built its own cleaning and processing plant, with the help of Inca Organics and the Canadian development fund, and the number of teachers it employs has gone from a handful to 40. By the third year, Inca Organics could follow standard business practice and pay for the quinoa after harvest. The Leventrys have become ambassadors for Ecuador in all the United States, and especially for quinoa. They have sold ERPE quinoa to some of the largest natural foods stores, including the Midwestern stores of the national Whole Foods Markets chain. The surest result is the annual increase in the average income of the farmers who grow organic quinoa for ERPE: from USD 230 to almost USD 450.

Citation for Slow Food Award

For creating a means of social, cultural and economic growth for indigenous populations of the Ecuadorian Andes. For helping to improve the standard of living and health of these people by setting up advanced organic methods of farming quinoa, a traditional product of their food culture. For giving shared significance to a means of mass communication while encouraging progress and preserving identity.