December 7, 2002 - Reuters: Peace Activist Phillip Berrigan Dies at 79

Peace Corps Online:

Peace Corps News:

Headlines:

Peace Corps Headlines - 2002:

12 December 2002 Peace Corps Headlines:

December 7, 2002 - Reuters: Peace Activist Phillip Berrigan Dies at 79

Peace Activist Phillip Berrigan Dies at 79

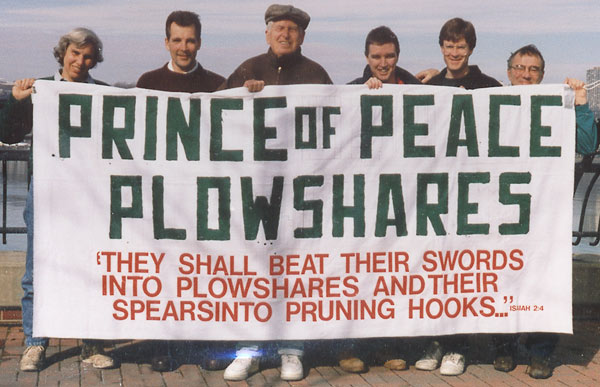

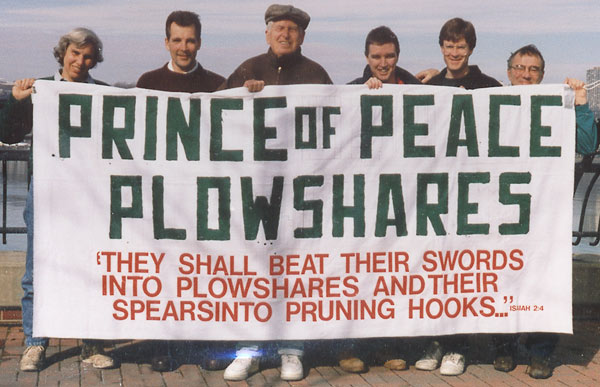

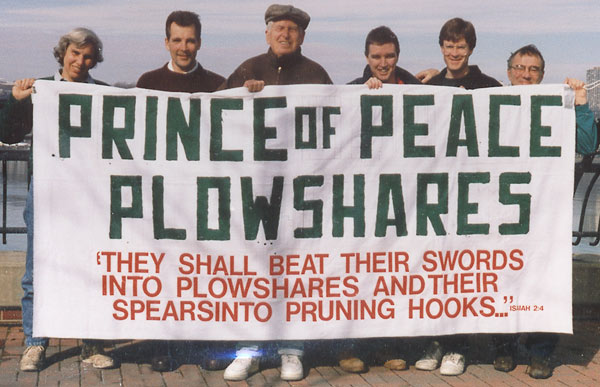

Caption: Before dawn on Feb. 12, 1997, Ash Wednesday, the beginning of the Christian season of Lent, six religious peace activists, Steve Baggarly from Norfolk, Vir., Philip Berrigan, a former Josephite priest from Baltimore, Mark Colville of New Haven, Conn., Susan Crane, from Baltimore, Tom Lewis-Borbely of Worcester, Mass. and the Rev. Steve Kelly, a Jesuit priest from San Jose, Calif., calling themselves Prince of Peace Plowshares, boarded the USS The Sullivans, an Aegis destroyer, at the Bath [Maine] Iron Works (BIW). Inspired by Isaiah's prophecy to turn swords into plowshares, they poured their own blood and used hammers to beat on the hatches covering the tubes from which nuclear missiles can be fired and unfurled a banner which read Prince of Peace Plowshares, "They shall beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks. Isaiah 2:4.

Read and comment on this obituary from Reuters for Phillip Berrigan, a former priest who was at the forefront of the American anti-war movement for the past four decades, who died on December 6, 2002 at:

U.S. Anti-War Activist Berrigan Dies at 79*

* This link was active on the date it was posted. PCOL is not responsible for broken links which may have changed.

U.S. Anti-War Activist Berrigan Dies at 79

Sat December 7, 2002 06:58 AM ET

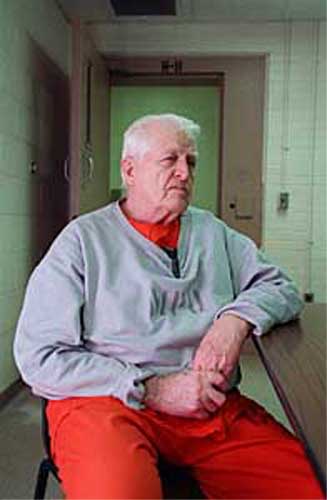

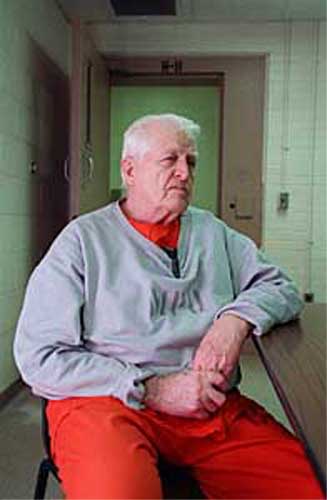

BALTIMORE (Reuters) - Philip Berrigan, a former priest who was at the forefront of the American anti-war movement for the past four decades, died late Friday, the Baltimore Sun reported. He was 79.

Berrigan, died of liver and kidney cancer at Jonah House, a communal living facility for war resisters in the Baltimore suburb of Catonsville, the newspaper reported on its Web site on Saturday.

The former Roman Catholic priest who was ordained in 1955, gained national prominence when he led a group of Vietnam War protesters who become known as the Catonsville Nine, in staging one of the most dramatic protests of the 1960s.

The group, which included his brother Daniel, a Jesuit priest, doused homemade napalm on a small bonfire of draft records in a Catonsville, Maryland, parking lot and ignited a generation of anti-war dissent. More recently he helped found the Plowshares movement, whose members have attacked federal military property in anti-war and anti-nuclear protests and were then often imprisoned.

In a final statement released by his family, he said, "I die with the conviction, held since 1968 and Catonsville, that nuclear weapons are the scourge of the earth; to mine for them, manufacture them, deploy them, use them, is a curse against God, the human family, and the earth itself."

Berrigan persistently and publicly criticized the Vietnam War and U.S. foreign and domestic policy and his defiant protests led him to serve some 11 years in jail and prison.

Howard Zinn, professor emeritus at Boston University who maintained a friendship with Berrigan through the years because they had similar views, called him "one of the great Americans of our time," the Baltimore Sun said. "He went to prison again and again and again for his beliefs," said Zinn.

Berrigan saw his protests as "prophetic acts" based on the Biblical injunction to beat swords into plowshares.

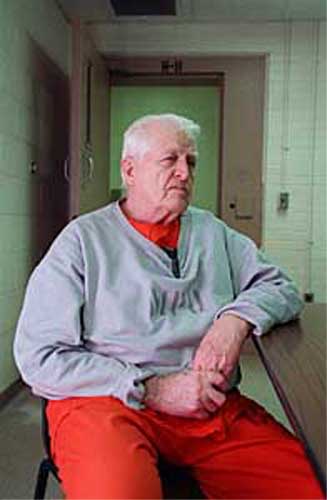

In his most recent clash in December 1999, Berrigan and others banged on A-10 Warthog warplanes in an anti-war protest at an Air National Guard base. He was convicted of malicious destruction of property and sentenced to 30 months. He was released on Dec. 14 last year.

His first arrest came in the early 1960's during a civil rights protest in Selma, Alabama.

Philip Francis Berrigan was born Oct. 5, 1923, in Two Harbors, Minnesota.

Phil Berrigan --The legacy

Read about Phil Berrigan's legacy at:

Phil Berrigan --The legacy

Phil Berrigan --The legacy

Phil Berrigan will live on, as his students live their principles It seems trite to say that when an influential person -- in the best sense of the term -- dies, that his work and vision lives on. We live in a society that forgets very quickly. In Palestine, they're still debating the fine points of 1948; in Iraq, the recitation of 19th century colonial horrors is only a fresh chapter in a 5,000+ year saga of power and its corruptions. But here in America, even Osama bin Laden is so last year. Can any of us talk seriously about legacies?

To which, two words suffice: Phil Berrigan. Not that he can talk at the moment; he lies mute and near death from cancer at his home in Baltimore's Jonah House, the radical Catholic Worker community he and his partner, Liz McAllister, founded nearly three decades ago. But especially after his death, there will be days and weeks of such talk -- and then years and decades in which Phil's legacy, in living blood, asserts itself.

As it happens, Phil's legacy of a lifelong commitment to principled nonviolent resistance to the most powerfully violent regime in world history -- ours -- lives on quite literally in his three children. I haven't seen Jerry or Kate in years, but Frida is one of the finest activists, young or otherwise, I know, and both Jerry and Kate are similarly well-respected. As any parent can attest after trying to teach their kid a moral code and then watching him or her march resolutely in the opposite direction, that's a remarkable achievement in itself -- and while Dad was in prison for a good chunk of their childhood, Liz wasn't, and neither was the entire community Phil and Liz helped bring together.

But Phil has touched many, many other lives during his life, not just through Jonah and through the Plowshares resistance movement he helped found, but through continuing active -- maybe too active -- participation in both for the rest of his life. That example, more than any words, is what has made Phil so special -- not just in radical Catholic circles, where he has long been viewed with a combination of deep love, awe, and exasperation, but among countless others who seriously aspire to living out their moral beliefs, especially in times dramatically at odds with those beliefs. He is a teacher, in the best sense of teaching by both words and example.

I had the opportunity to be a student for a while; when Phil and three others did their hammer and blood thing on board the nuclear warship USS Iowa, during a public tour at the Norfolk Naval Base on Easter morning in 1989. The Atlantic Life Community -- the mostly Eastern seaboard network of Catholic Worker communities and activists that, among other things, is a family reunion of Plowshares activists -- needed a volunteer to go down to Norfolk and be a full time support person, dealing with the jail and with the local community, for about six weeks.

I was available, and I had experience; I'd recently done several direct actions (and jail time), on peace and nuclear issues, in the conservative South. So, I went. It was an education -- not just because of Phil, but through meeting entire communities, locally and throughout the ALC, of inspiring and deeply committed activists. Mostly for health reasons, my days of risking prison for my beliefs have long passed; but I'm better for having done it, and fearlessly living my beliefs is an aspiration that's stuck with me ever since.

It's striking how few well-known activists of Berrigan's generation carried on, in a public way, with the radical views that brought them national prominence during the Vietnam era: Tom Hayden, perhaps, and Dave Dellinger. After that, there's a small (anti-)army of former CO's and Black Panthers and SDSers and Freedom Summer organizers who've gone on to become pillars of their local communities. But Phil, and perhaps his brother Daniel, are unique in that they went on to define themselves not by the acts that brought them celebrity, but by what they did with that celebrity.

In Phil's case, his liaison with McAllister, and their creation of Jonah House, was deeply controversial within the Catholic left when it happened. Incautious prison correspondence between the then-secret lovers was used in the infamous Harrisburg trial, in which casually written words were used to justify the preposterous charge of conspiracy to kidnap then-and-now war criminal Henry Kissinger. The Harrisburg defendants were vindicated, but ultimately, the government won: the cost in time, money, and emotion of defending Harrisburg all but destroyed the Catholic anti-war movement, and a lot of people at the time blamed Phil and Liz.

From that dicey history came a community that lives long after such internecine bickering has been forgotten: Jonah House, and a host of other, similar Catholic Worker houses around the country that see their mission as not only voluntary poverty and community service, but using their community to support members' lifelong commitments to challenging Fortress America. The form many of those challenges take, the Plowshares movement, is also a Phil Berrigan legacy; he was one of the eight actionists who hammered on the nose cone of a nuclear missile in the very first Plowshares actions, in September 1980 at a GE weapons facility in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania.

The next two decades, into and through his old age, were from that point a revolving door for Berrigan between Jonah House and prison; he probably touched as many or more lives inside prison walls as outside. Moreover, there have been scores of such actions since in the U.S. alone, and dozens more around the world. The Norfolk action was one. The June 1999 Trident Three case, in which three British anti-nuke campaigners were acquitted when a Scottish court for the first time in the world used as precedent the World Court's ruling that nuclear weapons were illegal, was Ploughshares, too. (The Brits and their spellings...) So was an action this fall in which Maryknoll nuns "disarmed" a missile silo in Northeastern Colorado. One of those nuns is a personal friend: 67-tear-old Jackie Hudson, a member of the Ground Zero Center for Nonviolent Action, housed across the street from the Bangor (Washington) Naval Base, home port to the Navy's Pacific fleet of nuclear submarines. She's an inspiration, too. And such actions will continue, long after Phil's passing.

They'll continue -- law enforcement charges of "domestic terrorism" notwithstanding -- for the same reason that the Plowshares movement, and Phil's post-Vietnam work in general, has labored in relative obscurity even within the left, even among many peace activists. The Plowshares notion of "disarming" does not so much concern the targeted missiles or other war machineries themselves (though the damage has sometimes been tremendous). It is a personal statement, one born of faith (Christian or otherwise) and not much based upon the pragmatic notion of trying to call a nation's attention to bad public policies as a step in the process of changing those policies. Plowshares actions tend to center instead around personal desires for accountability, between the actionist and her or his Creator, and the psychic "disarming" of a society whose all-pervasive brutality threatens that relationship. It says not only "my country is wrong," but "I refuse complicity." Plowshares is a form of witness, not lobbying. Silence or inaction, as ACT-UP famously reminded us, is a form of complicity.

Because Jonah House-style communities and actions like those of the Plowshares movement are based not on an issue or issues, but on the application of moral principles to whatever issue is at hand, Berrigan's legacies -- both the institutions and the people drawn to them -- will last far longer than many flavor-of-the-month progressives and their causes. Phil, and the many people he has worked with over the past three decades, take those principles very seriously. The commitment that Phil Berrigan modeled -- to enter into nonviolent resistance as a lifestyle, and as a powerful force for both personal and political change -- is long-term.

Ultimately, that's Berrigan's most influential gift to us. It is why we remember the Berrigans, the Thomas Mertons, the Dorothy Days, the A.J. Mustes, Dave Dellingers, Martin Luther Kings and Nelson Mandelas and Mohandas Gandhis. Jonah House, and other, newer efforts like the Nonviolent Peaceforce, are based on the belief that our world's epidemic of warmaking will never be seriously challenged until the enormous amount of money, time, creativity, and will that goes into making and using the plans and machines of war is somehow matched by those of us who are appalled by the devastation that invariably results. Now -- as people like George Bush and Dick Cheney plunge us into what they promise, seemingly with some degree of glee, to be a 50- or 100-year continuous war -- is a particularly good time to take inspiration from Phil's example of peacemaking as a lifetime commitment.

With or without the particular form that Phil's work took, that commitment is by definition radical in every sense. Our country today has countless radicals who have taken their calling, indirectly or very directly, from Phil Berrigan.

Long after we've forgotten the ringing obituaries offered up by progressives who, often as not, ignored or distanced themselves from Phil Berrigan's activism while he lived, his living epitaphs will keep on hammering on nuclear warheads, pouring their own blood, feeding the hungry, housing the homeless, speaking truth to those who mistakenly think theirs is the greatest power, and taking serious risks in Phil's memory.

It's hard to imagine a better measure of greatness.

A Tale Of Two War Veterans: John McCain And Phil Berrigan

Read this article from the Boston Globe on two veterans of war - John McCain And Phil Berrigan - and how they view the world at:

A Tale Of Two War Veterans: John McCain And Phil Berrigan

A Tale Of Two War Veterans: John McCain And Phil Berrigan

by James Carroll

John McCain's widely irresistible story does not begin with his valiant record as a prisoner of war. Nor is its most compelling aspect his role in bringing about an end to the punitive US embargo against Vietnam, although both accomplishments have stirred admiration in unlikely breasts, including mine. Rather, the episode that starts the McCain saga is one that few, including the senator himself apparently, have much reflected upon, yet it points to the most important - and troubling - aspect of this man's character. And that event bears comparison to another that occurred on the same day, launching an opposite saga.

On Oct. 26, 1967, McCain flew his A-4E Skyhawk, a single-seat attack bomber, toward a target in North Vietnam. His story begins when a surface-to-air missile hit the warplane above Hanoi, with well-known devastating results. But to understand the meaning of McCain's experience, other events just before and after must be considered, for that month was the pivot on which the entire arc of America's war in Vietnam turned.

By the beginning of that autumn, it had become clear to many military analysts that the war was being lost, and, in particular, that the air war was boosting North Vietnamese resolve, instead of undercutting it. That led Robert S. McNamara to turn against the war he had begun, and he now urged a bombing halt. ''The sole strategy for knocking the North Vietnamese out of the war from the air, McNamara concluded,'' as Stanley Karnow summarizes it, ''would be some form of genocide.'' Or, as McNamara himself put it, ''the virtual annihilation of North Vietnam and its people.''

In late October, Lyndon Johnson decided against McNamara, and ordered an escalation of the bombing. He approved, in Karnow's words, ''air strikes against 57 new North Vietnamese targets - nearly half of them in heavily populated areas ...'' And one of the first pilots given that mission was McCain.

The target toward which he so fatefully flew on Oct. 26 was, in the phrase of his biographer Robert Timberg, a ''previously off-limits'' power plant. The civilian infrastructure of Hanoi was now to be hit. McCain was an instrument of Johnson's escalation, which would quickly be exposed as the most terrible miscalculation of his presidency. Within weeks, McNamara would be out, and Eugene McCarthy would be in as a candidate for president.

Soon thereafter, Johnson, declining to run for reelection, would attempt to reverse his expansion of the air war, but a savage momentum had been unleashed. The most immoral aspect of America's war was then reified in the half-blind, ever more futile bombardment from the air, which would continue for five more years.

The imprisoned McCain could be expected to have no qualms about the air war, and he had none. His courageous clinging to an ideal of national honor is what endears him so widely. Yet, given the literal and symbolic significance of his place in the avant-garde of the strategic blunder - and moral catastrophe - that the escalated air war became, is it unreasonable to ask now for some reconsideration of a deeper meaning of honor?

McCain as the beloved icon of personal honor has reinforced a general American reluctance to face the national dishonor of American war-making, and he himself shows little or no ability to think deeply on this most crucial subject. That is why McCain's responses to contemporary questions of military policy, from Kosovo to the Missile Defense Shield, are so shockingly hawkish, far more appropriate to a young fighter jock than to a would-be statesman. He is an icon of escalation.

Consider, in contrast, the story of another young military man who specialized in ''killing from a distance,'' as his biographers Murray Polner and Jim O'Grady put it. He was an artillery spotter whose big guns shelled German-occupied cities during World War II, but ''the vast accidental cemeteries'' that he saw as his handiwork after the war changed him forever. And, as fate would have it, this veteran responded to Johnson's escalation on the same day that McCain did, but differently. On Oct. 26, 1967, he drew blood from his own arm, and then, the next day, with three others, he poured that blood on draft files at the Custom House in Baltimore - the first of what would be a dramatic escalation of peace movement protests.

That war veteran's name was Phillip Berrigan, and his time in prison for those protests would overlap with McCain's, and go on. After Vietnam, Berrigan's became a voice crying in the wilderness of unchecked American nuclearism.

Today, while McCain runs for president, the 76-year-old Berrigan is in jail in Baltimore again, awaiting trial for the December crime of having hammered, and once more poured his own blood, this time on the fuselage of an A-10 bomber at an air base in Maryland. The A-10, used in Iraq and Yugoslavia, fires ''depleted uranium'' weapons, which generate radioactive dust and represent another US escalation. Escalation forever.

The war protester and the war hero began their roles in this drama on the same day, but while Berrigan understands the American war story for the tragedy it is and lives accordingly, McCain sees it as an epic romance. Berrigan, in jail, is the truly free man, while McCain remains imprisoned in an unexamined sense of martial honor, which, in a president, would be truly dangerous.

James Carroll's column appears regularly in the Globe.

###

© Copyright 1999 Globe Newspaper Company

Click on a link below for more stories on PCOL

Some postings on Peace Corps Online are provided to the individual members of this group without permission of the copyright owner for the non-profit purposes of criticism, comment, education, scholarship, and research under the "Fair Use" provisions of U.S. Government copyright laws and they may not be distributed further without permission of the copyright owner. Peace Corps Online does not vouch for the accuracy of the content of the postings, which is the sole responsibility of the copyright holder.

This story has been posted in the following forums: : Headlines; Peace; Obituaries

PCOL1639

50

.

I want to make your subscribers aware of the US Peace Memorial Foundation and the US Peace Registry. Many of them may qualify to be listed.

Please go to www.USPeaceMemorial.org