September 23, 2003 - Government Executive: RPCV Congressman Chris Shays finds USAID plagued by staffing problems

Peace Corps Online:

Peace Corps News:

Peace Corps Library:

USAID:

September 23, 2003 - Government Executive: RPCV Congressman Chris Shays finds USAID plagued by staffing problems

- AID Saturday, November 15, 2003 - 7:59 pm [4]

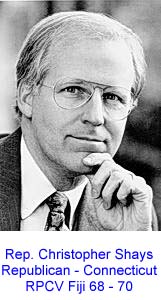

RPCV Congressman Chris Shays finds USAID plagued by staffing problems

Read and comment on this story from the Government Executive that poor funding, planning and oversight have led to critical staffing shortfalls at the U.S. Agency for International Development. RPCV Chris Shays, Chairman of the Subcommittee on National Security, Emerging Threats, and International Relations commented that "I get the feeling that you’re trying to keep your head above water so you don’t drown."

According to the General Accounting Office, while officials at AID are taking the necessary steps to better manage its workforce and recruit new employees to shore up shortfalls in skills at the agency, AID needs to ramp up its efforts. “We made the same recommendation in this report that we made 10 years ago,” testified Jess Ford, director of GAO’s International Affairs and Trade Division. “I don’t think it should take another 10 years to do it.” Read the story at:

AID plagued by staffing problems*

* This link was active on the date it was posted. PCOL is not responsible for broken links which may have changed.

AID plagued by staffing problems

By Tanya N. Ballard

tballard@govexec.com

Poor funding, planning and oversight have led to critical staffing shortfalls at the U.S. Agency for International Development, lawmakers concluded during a House Government Reform subcommittee hearing Tuesday.

“We have so many mandates and so little funding and everything is a priority,” John Marshall, AID’s assistant administrator for management, told members of the House Government Reform Subcommittee on National Security, Emerging Threats and International Relations.

AID was created in 1961 to provide assistance to strategic U.S. allies, provide humanitarian relief and help foster economic growth in the world’s poorest countries. During the past few years, Congress has insisted that the agency work in particular countries or with particular contractors, essentially taking control of the agency’s budget away from AID officials, Andrew Natsios, AID’s current administrator, has said. Consequently, the agency’s workforce shriveled by 37 percent during the 1990s. At the same time, countries with AID programs doubled, stretching the already diminished workforce. On Tuesday, Marshall outlined the agency’s problems for the committee, pointing to AID’s aging workforce and an ever-widening gap in critical skills needed to meet the agency’s various missions.

“The entire agency, both in headquarters and the field, is struggling to make up for the loss of its institutional memory and the right people are not yet aligned with mission goals in the most cost-effective and safe ways,” Marshall testified.

In some countries, such as Iraq and Afghanistan, work space limitations and security measures sometimes hinder the agency’s ability to hire foreign nationals to work in their home countries, testified Barbara Turner, senior deputy assistant administrator for AID’s Bureau of Policy and Program Coordination. Because many of the agency’s offices are now located in embassies, workspace is limited and there is a reluctance to bring local hires into embassy compounds. Those constraints, coupled with new missions, have exacerbated the agency’s staffing problems, Marshall said.

“I get the feeling that you’re trying to keep your head above water so you don’t drown,” Rep. Chris Shays said.

Currently, agency officials are analyzing AID’s workforce, comparing the agency’s skill levels to its needs with plans to address those gaps through recruitment, training and outsourcing. However, Marshall said the results of these efforts might not be seen for several years.

According to the General Accounting Office, while officials at AID are taking the necessary steps to better manage its workforce and recruit new employees to shore up shortfalls in skills at the agency, AID needs to ramp up its efforts. The watchdog agency released a report in conjunction with the hearing.

“We made the same recommendation in this report that we made 10 years ago,” testified Jess Ford, director of GAO’s International Affairs and Trade Division. “I don’t think it should take another 10 years to do it.”

Ford recommended that agency officials make workforce management a priority and implement the various plans AID officials have developed in response to the problem.

Executive Summary from the GAO Report on Staffing Problems at USAID

Read the Executive Summary from the GAO Report on Staffing Problems at USAID at:

Executive Summary from the GAO Report on Staffing Problems at USAID

August 22, 2003

The Honorable Christopher Shays, Chairman

The Honorable Dennis J. Kucinich, Ranking Minority Member Subcommittee on National Security, Emerging Threats, and International Relations

Committee on Government Reform

House of Representatives

Humanitarian and economic development assistance is an integral part of U.S. global security strategy, particularly as the United States seeks to diminish the underlying conditions of poverty and corruption that may be linked to instability and terrorism. Since 1962, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) has managed more than $273 billion in such assistance.1 In fiscal year 2003, Congress appropriated almost $11.5 billion to USAID, and the agency managed programs in almost 160 countries. Agency staff often work in difficult environments and under evolving program demands. More will be demanded of USAID’s staff as they implement large-scale relief and reconstruction programs in Afghanistan and Iraq while continuing traditional long-term development assistance programs.

USAID administers foreign aid through a decentralized staffing structure, with its headquarters in Washington, D.C., and missions located throughout the world. In 1993, we recommended that USAID develop a comprehensive workforce planning and management system to better identify staffing needs and requirements.2 However, human capital management continues to be a high-risk area at USAID and throughout much of the federal government.3 According to the Office of Management Budget (OMB), the federal government—including USAID—significantly downsized its workforce during the 1990s through across-the-board cuts rather than targeted reductions aligned with agency missions, and human resources planning remains weak in most agencies. The President’s Management Agenda, issued in fiscal year 2002, represents the administration’s effort to improve the performance of federal departments and agencies through 14 initiatives, including human capital management. OMB concluded that without proper planning, the skill mix of the federal workforce will not reflect tomorrow’s missions.4

In light of USAID’s long-standing workforce planning and management problems, you expressed concern about its ability to manage and oversee its foreign assistance programs. In particular, you expressed concern about USAID’s apparent inability to identify and readily address staffing requirements. At your request, we examined (1) the changes in USAID’s workforce since fiscal year 1990 and their effect on the agency’s ability to deliver foreign assistance and (2) USAID’s progress in developing and implementing a strategic workforce planning system.

To accomplish our objectives, we analyzed personnel data and workforce planning documents and interviewed knowledgeable USAID officials representing the agency’s regional, technical, and management bureaus in Washington, D.C. We conducted fieldwork at seven overseas missions— the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, Mali, Peru, Senegal, and the West Africa Regional Program in Mali. We also evaluated USAID’s strategic workforce planning efforts in terms of workforce planning principles used by leading organizations: ensuring the involvement of agency leadership, employees, and stakeholders; determining current skills and competencies and those needed; implementing strategies to address critical staffing needs; and evaluating progress in achieving human capital goals.

Results in Brief

Since 1990, USAID has continued to evolve from an agency in which U.S. direct-hire foreign service employees directly implemented development projects to one with a declining number of direct-hire staff that oversee the contractors and grantees who carry out most of its day-to-day activities. Personal services contractors—chiefly foreign national staff at overseas missions—play an increasing role in managing the development activities that are designed, implemented, and evaluated mainly by thirdparty contractors and grantees. As direct-hire staff levels decreased by 37 percent since fiscal year 1992, the number of countries with USAID programs almost doubled, and program funding recently increased more than 57 percent—from $7.3 billion in fiscal year 2001 to almost $11.5 billion in fiscal year 2003. As a result of the decreases in U.S. directhire foreign service staff levels, increasing program demands, and a mostly ad hoc approach to workforce planning, USAID now faces several human capital vulnerabilities. For example, attrition of its more experienced foreign service officers, difficulty in filling overseas positions, and limited opportunities for training and mentoring have sometimes led to (1) the deployment of direct-hire staff who lack essential skills and experience and (2) the reliance on contractors to perform most overseas functions. In addition, USAID lacks a “surge capacity” to enable it to respond quickly to emerging crises and changing strategic priorities. As a result, according to USAID officials and a recent overseas staffing assessment, the agency is finding it increasingly difficult to manage the delivery of foreign assistance.

In response to the President’s Management Agenda, USAID has taken steps toward developing a comprehensive workforce planning and human capital management system that should enable the agency to meet its challenges and achieve its mission, but progress has been limited. In evaluating USAID’s efforts in terms of proven strategic workforce planning principles, USAID has more to do. For example:

• The involvement of USAID leadership, employees, and stakeholders in developing and communicating a strategic workforce plan has been mixed. USAID’s human resource office is drafting a human capital strategy, but it has not yet been finalized or approved by such stakeholders as OMB and the Office of Personnel Management. As a result, we cannot comment on whether USAID employees and other stakeholders will have an active role in developing and communicating the agency’s workforce strategies.

• USAID has begun identifying the core competencies its future workforce will need and is conducting a workforce analysis and planning pilot at three headquarters units that will include an analysis of current skills and will eventually cover the entire workforce. However, it has not yet conducted a comprehensive assessment of the critical skills and competencies of its current workforce. USAID is in the process of determining the appropriate information technology instrument and methodology that will permit the assessment of its current workforce skills and competencies.

• USAID’s strategies to address critical skill gaps are not comprehensive and have not been based on a critical analysis of current capabilities matched with future requirements. USAID has begun hiring foreign service officers and Presidential Management Interns to replace staff lost through attrition. However, the agency has not completed its civil service recruitment plan and has not yet included personal services contractors—the largest segment of its workforce—in its agencywide workforce analysis and planning efforts.

• USAID has not created a system to monitor and evaluate its progress toward reaching its human capital goals and ensuring that its efforts continue under the leadership of successive administrators. Because it has not yet institutionalized a comprehensive workforce planning and management system, USAID cannot ensure that it has the essential skills needed to carry out its ongoing and future programs. To help USAID plan for changes in its workforce and continue operations in an uncertain environment, we recommend that the USAID Administrator develop and institutionalize a strategic workforce planning and management system that takes advantage of strategic workforce planning principles.

Background

USAID is the lead U.S. agency for administering humanitarian and economic assistance to about 160 countries. The USAID Administrator reports to the Secretary of State and receives overall foreign policy guidance from the Department of State. USAID operates its foreign assistance programs from its offices in Washington, D.C., and from missions and offices around the world.

In 1993, we reported that USAID had not adequately managed changes in its overseas workforce and recommended that USAID develop a comprehensive workforce planning and management system to better identify staffing needs and requirements.5

In the mid-1990s, USAID reorganized its activities around strategic objectives and began reporting in a results-oriented format but had made little progress in personnel reforms.6 In July 2002, we reported that USAID could not quickly relocate or hire the staff needed to implement a largescale reconstruction and recovery program in Latin America, and we recommended actions to help improve USAID’s staffing flexibility for future disaster recovery requirements.7 Appendix I summarizes several reports and studies prepared by GAO and others since 1989 that address USAID workforce planning and human capital management issues. Studies by several organizations, including GAO, have shown that highly successful service organizations in both the public and private sectors use effective strategic management approaches to prepare their workforces to meet present and future mission requirements. We define strategic workforce planning as focusing on long-term strategies for acquiring, developing, and retaining an organization’s workforce and aligning human capital approaches that are clearly linked to achieving programmatic goals. Based on work with the Office of Personnel Management, other U.S. government agencies, the National Academy for Public Administration, and the International Personnel Management Association, we identified strategic workforce planning principles used by leading organizations. According to these principles, an organization’s strategic workforce planning and management system should (1) involve senior management, employees, and stakeholders in developing, communicating, and implementing the workforce plan; (2) determine the agency’s current critical skills and competencies and those needed to achieve program results; (3) develop strategies to address gaps in critical skills and competencies; and (4) monitor and evaluate progress and the contribution of strategic workforce planning efforts in achieving program goals.

Click on a link below for more stories on PCOL

9/27/03

Some postings on Peace Corps Online are provided to the individual members of this group without permission of the copyright owner for the non-profit purposes of criticism, comment, education, scholarship, and research under the "Fair Use" provisions of U.S. Government copyright laws and they may not be distributed further without permission of the copyright owner. Peace Corps Online does not vouch for the accuracy of the content of the postings, which is the sole responsibility of the copyright holder.

This story has been posted in the following forums: : Headlines; USAID; Congress; GAO; COS - Fiji

PCOL7955

97

.

|

By USAIDNeed on Monday, September 29, 2003 - 10:21 pm: Edit Post |

I am glad to see Chris Shay's has put his attention on USAID. During the 1990's, I was disappointed that the mission and workforce was cut by 37%.

Personally, after graduating from graduate school, I applied for many different jobs with USAID. I was unsucessful. I really wanted to have a career with USAID. I have interviewed for too many jobs with them and contractors. During the late 1950's and 1960's, the US put out a tremendous effort in bilateral relations by creating USAID and hiring employees that were fundamentally under the GI bill.

Though my career goals did not go in the USAID's direction, I still try to keep abreast of their efforts. I still have a far off hope that someday I will work with them. However, I believe their personnel standards are too stringent. Many of my friends and colleagues feel the same way. Many of us have the skills, but are not welcome in the USAID world as it is today.

I look forward to seeing USAID hire the generation they forgot to hire.

Thanks,

Returned Volunteer

My personal exposure to USAID was limited, but unfavorable. The "USAID Type," seem to expect too much comfort in foreign lands, hold HCN in low esteem and only have fellow Americans as friends abroad. They never get to really know the people they are sent to help--the "common man".

As a RPCV who is now a USAID Health Officer, I welcome the GAO attention to the USAID staffing issue. For too long we have been asked to "do more with less". In the three years I have been in Bangladesh, my office has shrunk from 5 to 2 US Direct Hire positions with little change in the amount of funding and programs for which we are responsible. This process has been going on for a long time as the Congress has cut our operating expense budget as a percentage of program funds. The agency started in the past 5 years to increase its recruitment. While posted in Washington I sat on a selection committee for new health officers. We had 150 candidates for 16 positions. Therefore, we were able to select the best, using stringent personnel standards. The best qualified candidates were usually RPCVs, with an additional 8 years of professional overseas experience. However, USAID needs many more professionals. Worldwide next year there will be 26 positions open for US Direct Hire Health Officers, and only 15 persons bidding to fill them. I don't know if we will be able to fill the Deputy position in my office or not next year. Although almost half of the Health Officers in USAID are eligible for retirement, only 16 or so New Entry Professionals are being recruited each year to replace them.

Hopefully this study and your lobbying will make the Congress and Administration realize that it takes a cadre of professionals to manage USAID and they will loosen the purse strings to expand the USAID workforce. RPCVs will be one of the greatest beneficiaries of such a move.

|

By Anonymous (host-151.nbc.netcom.ca - 216.123.177.151) on Sunday, October 05, 2003 - 7:47 pm: Edit Post |

I am was saying that the CDC agreement was not a country agreement.

|

By USAIDNEED (0-1pool136-56.nas12.somerville1.ma.us.da.qwest.net - 63.159.136.56) on Saturday, November 15, 2003 - 5:32 pm: Edit Post |

Charles,

You are right on about Chris's advocacy. However, 100 plus candidates for 16 jobs is like the 1980's. You should just go to Fletcher and Harvard and choose RPCV's" who will go along and get along".

My professor in college served with USAID for fifteen years. At that time, they hired a new generation of Americans. They got the opportunity to really serve their country. They had a sense of mission that has never returned. A problem with USAID is not hiring the folks from Peace Corps who have experienced developing countries, gone back to graduate school, and have private industry experience. They hire people who will "tow the line" and not come up with new ideas. Once in a while you will see a break through, in the contracting world.

Henry Merrill

Sharon---- in Personnell.

I remember the time I really wasted trying to get in. If I added up the hours applying. I could have given USAID two free years of work.

That is what happens to folks who are RPCV's and don't get hired.

It is too political and stringent (stringent in a way which is not necessary). Like, what was your grade point average etc... USAID got volunteer time from most of us. The nation should be able to provide us with opportunity. Sorry we disagree.

The job search at USAID is stupid.

I wasted thirty thousand dollars going to graduate school and I don't feel my experience helped at all. 2,500 job applications and a true full force effort right to the top of government should not have to happen. When I get into a position to make these decisions, USAID will never do this to people who really want to serve.

That is unamerican.

All I wanted was a med level job.

This is the tragedy of a lost generation of USAID workers.

|

By RPCV/former CD/current business owner (203.41.171.66.subscriber.vzavenue.net - 66.171.41.203) on Thursday, January 15, 2004 - 1:09 pm: Edit Post |

As a professional with over a decade in the private sector, an additional decade in the non-profit and government sectors and including 12 years overseas, I thought USAID might offer an avenue to continue working in international development. Perhaps. However, I was told by a senior officer that a mid-career professional would not be able to enter above the FS-04 level and that USAID's culture places a very high premium on years with USAID as opposed to overall years, quality and diversity of experience.

USAID should indeed apply stringent standards in hiring personnel. The most capable should be selected. However, this agency needs to be more creative and expansive in its sourcing of candidates at all levels. FS 04 for an experienced professional who could contribute meaningfully to the USAID mission is a ridiculous step down, FS05 being the lowest FSO level and a GS 11 or so equivalent. If a person is more qualified than another who has put in X years with the agency, shouldn't that person nevertheless be allowed to compete (I mean meaningfully, effectively compete ... not simply on paper to meet regs)at a higher level?

USAID is in need of a major change in organizational culture if it is to emerge from its bureaucratic quagmire to become truely effective in international development. I've witnessed far too many failed USAID projects, driven my a mentality of getting the funds spent and making the indicators look favorable on paper within an overly burdensome reporting process. Many of the ideas contained in the MCA plan are worth adapting at USAID.

Contractors place the highest premium on applicants who can demonstrate the bureaucratic art of USAID-specific proposal writing and reporting and share a sense of indicator idolatry. These are mechanics that can be mastered fairly quickly by any reasonably intelligent and competent professional who knows how to write a good proposal, etc. I've lost count of the positions announced for which I qualify very well, except for the requirement of having worked on a USAID project in the past and having previously written a USAID proposal. Requiring a writing sample focused on a development project is certainly reasonable, but must it have been for a USAID project?

Why did the current administration decide to expand development funds through an organization separate from USAID? I assume a lack of faith in USAID is involved. An organizational review similar to what NASA has been undergoing in the wake of the shuttle disaster would be useful for USAID as well.