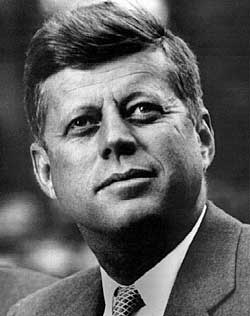

Kennedy said the Peace Corps "...will be really serious when there are at least 100,000 Peace Corps Volunteers a year who go to work and live in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Because then, after one decade, there will be a million Americans with first-hand experience in the problems of this world, and we will for the first time have a large political constituency for an informed public opinion about foreign policy.” says Sen. Harris Wofford

Panel—"The Liberal Arts: Privilege and Responsibility"

Sen. Harris Wofford

Amherst College Inauguration Panel

October 26, 2003

I will try to resist the temptation to roast and toast Tony and Karen. But I do want to toast the Board for their boldness and wisdom in picking Tony as Amherst’s 18th president. Echoing John Kennedy and Robert Frost, Tony put forward the proposition that we need to have an unsparing instinct for reality.

The reality about “The Liberal Arts: Privilege and Responsibility”—the topic for our panel discussion—is that liberal arts colleges have plenty of privilege but are falling very far short of their responsibility—particularly their responsibility to lead us, to educate us to understand the world, and to live up to our ideals. And as Tony said this morning, that is what the core mission of a college should be.

In his Opening Convocation address earlier this year (delivered, I think, in this hall, where Alexander Meiklejohn looks down from the wall), Tony sent a clarion call for Amherst to reenter the great debate about where our nation and the world are heading, and where we all ought to be heading.

The reality is that if the liberal arts colleges of America were fulfilling their responsibility, there would be a lot more active-duty citizens in this country. Not only citizens who vote, but citizens who go on to the social invention and the constructive action that are necessary to solve our most complicated problems, at home and around the world. And there is nothing that this nation and the world need more than Americans who understand the world’s complications, including the problem of diversity in our own nation and the integration of the white minority into a world where the great majority are people of color. However Christian America may or may not be, we must learn that to live together in a world where Judeo-Christian society is far outnumbered by Hindu, Buddhist, and Muslim societies, to name only three.

Let me confess that I have a case of millennium blues that drew during a vivid trip around the world this spring with my 14-year-old grandson. When I was 12 years old, my grandmother took me around the world for six months, and I am committed to taking my grandchildren around the world, too—but now the world moves faster, so these trips are for six weeks, not six months. This trip was deeply discouraging. It was exhilarating when we tracked gorillas in western Uganda, and there were, of course, other moments of real adventure. But having been around the world a number of times and lived in different parts of the world, I was dismayed to sense the growing gap between the American people and the Arab and Muslim world—and the gap between America and other great parts of this world, too.

For me, there have been seven decades of cycles of hope—and disappointment.

The first cycle of hope began, in a strange way, with Pearl Harbor. After my world trip on the eve of World War II, I became an ardent interventionist. The isolationists were blocking action that went beyond the inadequate policy of “support the allies without going to war”. Pearl Harbor ended that great debate. And then we saw an amazing mobilization of America that showed what could be done when there was a great, simple, clear national purpose: winning a war that we had to win. We not only discovered how to the atomic bomb; we demonstrated that we could crack the atom of civic power and harness it for an essential national goal.

The colleges’ and universities’ role in research that helped us win that war became clear to me in 1946, when I entered the College at the University of Chicago. There at the University’s Stagg Field we saw the plaque that marked the first nuclear reaction in the history of mankind. And we were at the college where the president, Robert Maynard Hutchins, took up the kind of challenge Tony was asking Amherst to take on today. In effect, Hutchins said, “My God! We helped make this bomb; now we must figure out how to get a world of law and peace.” He formed the Committee to Frame a World Constitution. I looked out of my dormitory window at the building where that draft of a world constitution was being argued by some extraordinary academics and others. I became involved in the cause of a world organization with power to keep the peace grew in strength on many campuses.

Coming out of that war, General Marshall went to Harvard and proposed the Marshall Plan. At Chicago and colleges and universities around the country, students and faculty and their presidents called for its enactment by Congress. Can you imagine what kind of investment that would represent in today’s dollars?

There was a tremendous sense of hope about what could be done in the world. Then the Cold War closed in, and we were consumed with the reality of the Cold War. Of course the Iron Curtain was a real thing, and the Soviet Sputnik going into space ahead of our effort was a real challenge. But it was frustrating to live with the reality that hardly anything requiring major national resources could get attention unless it was claimed to be a way to stop the Russians. Thanks to Sputnik there was, for a while, growing interest in teaching mathematics. But as Roosevelt said of the 1920s, these were long, hard, gray years for those of us who had a different vision of the world.

Then there was the hope, on the homefront, that sprang up in the civil rights decade. Rosa Parks said No, and Martin Luther King said Yes. King showed what bold and courageous social invention could accomplish; what civil disobedience and constructive service together could do. And there was a joining of popular protest and public power—the two hands at last clapped. And the great civil rights laws of 1964 and 1965 were enacted and enforced. The mother-in-law of our panelist Sheldon Hackney, Lucy’s mother, and Tony’s and my friend, Virginia Durr, was there with Martin Luther King at the church meetings night after night; she was the leading white woman in Montgomery to support King from the beginning.

Within ten years, the two goals of that movement—winning the right to vote and ending public segregation—were achieved. And many students and some faculty and a few college presidents were in the forefront and played notable parts, including of course the students who started sit-ins in the South.

But then King and Robert Kennedy, like President Kennedy, were killed and the Viet Nam War consumed our attention, dividing the nation, and also divided us from the world in many ways. The wind went out of our sails in the depression of the national spirit in that unhappy cycle.

The battle to bring down the walls of segregation had been won, but the new challenge was not to protest but to build. Impatient wild ones were saying, “Burn, baby, burn” but King’s answer was “Learn, baby, learn,” and “Build, baby, build.” In the thirty years that followed so little of the new learning and new building that was needed was done. And higher education did so little to take us on to the next level in making equal opportunity a reality everywhere in our land.

Take one example. The Peace Corps, to the surprise of many skeptics, proved successful and became non-controversial. But as Kennedy sent the first volunteers off from the White House lawn, he had turned to some of us who were helping Sargent Shriver, and said, “This will be really serious when there are at least 100,000 Peace Corps Volunteers a year who go to work and live in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Because then, after one decade, there will be a million Americans with first-hand experience in the problems of this world, and we will for the first time have a large political constituency for an informed public opinion about foreign policy.”

In his message to Congress proposing the Peace Corps Kennedy had said, “One of the prime carriers of the Peace Corps should be colleges and universities. In doing so, American higher education can help our colleges become world colleges and world universities.” This was a creative challenge to higher education. Under Father Hesburgh’s leadership, Notre Dame took up the challenge. They organized, recruited, and ran the Peace Corps in Chile, and they did it for some years with great work in Chile and vital impact on Notre Dame. Western Michigan University had a five-year Peace Corps degree—including putting the two years of service working overseas. A number of universities got contracts to train the Volunteers, and Dartmouth led the way in training for French-speaking Africa. But few institutions of higher education rose to the occasion and engaged on a large scale. If they had, I believe Kennedy’s hope could have been realized, and instead of the less than 200,000 Volunteers serving all-told over 42 years, there might indeed have been a million in each decade. Those millions of far better informed Americans could be making a difference now in our relations with the world.

We are having the same disappointing experience with national service in AmeriCorps today. Most of the now 50,000 AmeriCorps members are working to meet the special needs of children and youth. Colleges and universities with their students should be the organizers and carriers of an educational venture like that. Such education in action is one of the key ways to prepare a new generation of Americans to deal more effectively with the hard problems of our time.

Yeats said, “In dreams begins responsibility.” I’ve indicated some of my dreams about American education. And in his Inaugural address today, Tony has beautifully restated the dream of America.

The first proposition of the first Federalist Papers was that “it seems to have been reserved to the people of this country, by their conduct and example, to decide the question whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their constitutions on accident and force.” Reflection on good government should be a central purpose of higher education, and especially of liberal arts colleges. Americans need an education that equips them not only to understand the world but also to choose and act. I look forward to what Tony and Amherst can do to help decide the question in favor of reflection and choice—to stir the world of higher education to do its part to see that our destiny is not left to accident and force.

Tony, your predecessor, Alexander Meiklejohn, came into my life fifty years ago and made me realize what a college president ought to be. I remember his delight as he told me that decades after he had been fired at Amherst, he was invited back by the Trustees to give a convocation address, in this very hall I think. Trustee John McCloy, a student of Meiklejohn’s, had arranged for the board to meet very early in the morning so they wouldn’t be late to hear their legendary president. And Alex, in his provocative way, began his talk by saying, “I am delighted to see I can still stir the Trustees from their customary sloth.”

I was introduced to Alex Meiklejohn by another Amherst man, Scott Buchanan, the philosopher who shaped the Great Books curriculum of St. John’s College. He was the main teacher in my life. Tony practices some of the watchwords that Amherst’s former student and teacher preached. Meiklejohn’s student Scott Buchanan made contagious the Socratic rule to follow the question where it leads. Over many years now, it’s been fascinating to watch Tony as he follows the question where it leads. It led him into action in the world, in South Africa—and in this country, in our public school systems. And it also led him into study and scholarship and reflection. That’s the combination that we need.

I’ll close with another advice I heard Scott Buchanan give half a century ago in a Commencement talk at St. John’s. He said that, “The systems you are going out into, and the apparent realities of the world, for all their high and mighty poses…are only possibilities which with boldness, laughter, and ingenuity on our part can be put aside and replaced.”

So this is my hope for you, Tony. May you and Amherst become a leading factor in a new cycle of hope in American education. I believe you can do so—with boldness, laughter, and ingenuity.