Shriver: The ‘Good Kennedy’ stands apart

Shriver: The ‘Good Kennedy’ stands apart

By Deborah Kalb

For much of his life, Sargent Shriver was known as a Kennedy in-law. Today, at age 88, he may be best known as the father-in-law of California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. “There is a certain fitting irony that, as he fades into the twilight, he should once again find himself being eclipsed by an in-law,” Scott Stossel writes in his new biography, Sarge.

But, as Stossel amply demonstrates, Shriver’s life story stands quite well on its own.

Stossel — an Atlantic Monthly editor selected by Shriver to work with him on what originally was planned as an autobiography — delves deeply into his subject’s multifaceted past, including Shriver’s childhood in Maryland and New York, his service in World War II, his role as Peace Corps creator, his unsuccessful vice-presidential and presidential bids, and his involvement in the Special Olympics.

Shriver’s relationship with the Kennedy family plays a major role in the book — as it clearly has in Shriver’s life. Newly returned from his wartime military duties in the Navy, Shriver met the dynamic Eunice Kennedy. He also met Eunice’s father, the redoubtable Joseph P. Kennedy, who offered the young Shriver a job — first in New York and then helping to manage Kennedy’s 4-million-square-foot Merchandise Mart building in Chicago.

Shriver’s lengthy courtship of Eunice, a source of amusement to her brothers, eventually resulted in their marriage in 1953. As an in-law — even one trusted by the family patriarch — Shriver faced a strange dynamic when it came to his Kennedy ties. On the positive side, the Kennedy connection provided him with contacts galore. But on the other hand, Shriver, who had political dreams of his own, was expected to put his ambitions on hold and yield to those of his brothers-in-law: first Jack, then Bobby and then Ted.

“Shriver was, it might be said, ‘the Good Kennedy’: in his idealism, heartfelt Catholicism, and commitment to Democratic politics and public service, he was perhaps more Kennedy than the Kennedys — and yet he was also, in his personal rectitude, moral probity, and gentle kindness, less Kennedy than they were,” Stossel writes. “He was in the Kennedy family without being fully of it.”

In some ways, Stossel’s portrait of Shriver leaves one exhausted. Clearly, the man had, in his prime, an almost superhuman energy level, working seven days a week at the Peace Corps and as head of President Johnson’s War on Poverty (Shriver’s decision to continue in the new Johnson administration after JFK’s assassination offended some in the Kennedy camp).

“By all accounts, he averaged an eighteen- to twenty-hour workday between 1964 and 1968, when he stepped down as the OEO [Office of Economic Opportunity] director,” Stossel writes. “His family rarely saw him. ‘When I look back now,’ says Sarge’s eldest son, Bobby, ‘I think to myself, “Wow, I never saw my father for the whole 1960s.”’”

Even in recent years, Shriver has retained his buoyancy. In 2000, at 85, Shriver flew to Beijing for a Special Olympics meeting and, although just off the plane, managed to play basketball with a group of children. And when he was diagnosed last year with the early symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, he wrote a letter to his friends explaining the situation Stossel describes as “totally representative of its author: cheerful, optimistic, forward looking, and a call-to-arms.”

The Shrivers have five children: four sons and a daughter, Maria, who left her NBC News duties after her husband, action-movie star Schwarzenegger, became governor of California last year. Political differences between the Democratic Shrivers and the Republican Schwarzenegger did not seem to matter; the whole Shriver family, not just Maria, showed up for Schwarzenegger’s victory party.

But it’s the Shriver sons — along with their Kennedy cousins — who feature in another new book, Laurence Leamer’s Sons of Camelot. Leamer — whose previous works include The Kennedy Men and The Kennedy Women — focuses here on the male Kennedys, from JFK’s assassination in 1963 to the present.

At times, Sons of Camelot reads like an unending litany of misfortunes and tragedies: Chappaquiddick, various Kennedys’ stays in rehabilitation centers for addiction problems, the William Kennedy Smith rape trial, John F. Kennedy Jr.’s fatal plane crash.

Perhaps unavoidably, the star of this book is JFK Jr.; the book begins with the 3-year-old saluting his father’s coffin as it passes by. Leamer goes on to describe the young man’s New York lifestyle, where he tried to balance his desire for a relatively normal existence with his inheritance of the Kennedy mantle. Various friends, including CNN’s Christiane Amanpour, cooperated with Leamer and are quoted frequently.

“Young John bore those mythic dreams [of Camelot], and as much as he tried to flee them, darting down Manhattan streets on his bicycle or flying above the clouds, they were always with him,” Leamer writes. “Those romantic, spiritual aspirations that drew millions to the name and ambitions of the Kennedys were born with the death of President Kennedy and much of it died with the death of his son.”

Leamer also probes into the lives of various other Kennedy men, including Sen. Edward Kennedy (D-Mass.); his son, Rep. Patrick Kennedy (D-R.I.); the late Sen. Robert Kennedy (D-N.Y.); and his seven sons, including former Rep. Joseph Kennedy (D-Mass.) and environmentalist Robert F. Kennedy Jr. But among the young generation of Kennedys — the grandsons of Joseph P. — no one beats Schwarzenegger for sheer political drive, according to Leamer.

“Arnold was a throwback to the willful ambition of Joseph P. Kennedy,” Leamer writes, adding, “Arnold had unbridled political ambition and will unlike any of the young Kennedys. While Joe and Patrick had walked away from running for higher office, Arnold had stood for governor without any administrative experience or previous public office.”

RFK’s sons, meanwhile, at least the older ones, are portrayed as troubled. One, David, died of a drug overdose; another, Michael, died in a skiing accident. “The devastating truth is that most of Ethel’s sons would become alcoholics or drug addicts,” Leamer writes. “Their home became a virtual machine for creating addiction.”

As a result, some of the other families, including the Shrivers, kept their distance, according to Leamer. “The Shrivers gently nudged Bobby and their other children away from Ethel’s family,” Leamer writes of the interactions at the Kennedy clan’s Hyannis Port compound. “The Smiths chose to protect their children by building a summer home on Long Island where Steve Jr. and Willie would not even see their notorious cousins. Jackie’s and Ethel’s houses were separated only by a tree, but Jackie made sure that her children kept away from their cousins next door.”

In his book, Stossel recounts a Hyannis Port anecdote that points out the differences between the Shriver kids’ upbringing and that of some of their Kennedy cousins: “Once, at Hyannis Port, one of Shriver’s young sons fell and hurt himself and burst into tears. Looking on, Bobby Kennedy said, ‘Kennedys don’t cry!’ Shriver picked up his son and said, ‘That’s okay, you can cry. You’re a Shriver.’”

In the end, these two books touch on some similar material but employ it in very different ways. Stossel’s is a serious work that focuses primarily on Sargent Shriver’s life in public policy and politics, while Leamer’s is far more gossipy. Kennedy-related books of all types abound; it all depends on what the reader is seeking.

Books reviewed

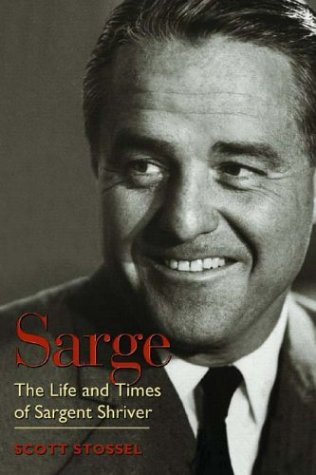

Sarge: The Life and Times of Sargent Shriver

By Scott Stossel

761 pages; $32.50

Smithsonian Books, 2004

Sons of Camelot: The Fate of an American Dynasty

By Laurence Leamer

638 pages; $27.95

William Morrow, 2004

© 2004 The Hill