The iceberg concept is routinely used in Peace Corps' World Wise Schools and in other multicultural training programs

Border Crossings in the Classroom

There are any number of ways to uncover the taken-for-granted nature of culture and engage the boundaries of culture.

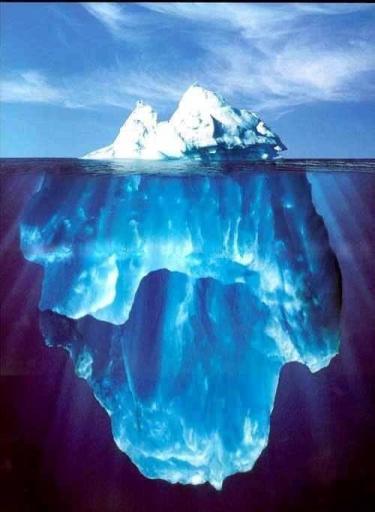

One useful way of teaching about culture is to represent it as an iceberg. The iceberg concept is routinely used in Peace Corps' World Wise Schools and in other multicultural training programs (Peace Corps 2002). Just as nine-tenths of an iceberg is hidden or under water, much of a culture lies outside of our conscious awareness. Above the water line are aspects people commonly associate with culture, such as food, dress, art, and literature. Below the water line, however, are practices and ideologies that we do not normally identify as culture but influence our lives and geographies nevertheless.

They include conceptions of beauty, relationships to animals, patterns of superior and subordinate relations, tempo of work, theories of disease, eye behavior and body language, and the arrangement of physical space. The iceberg concept of culture encourages students to think about culture in "deeper" and more critical ways. (A complete graphic representation of the iceberg concept is available for classroom use at http://www.coe.ohio-state.edu/dyfo rd/ culture.htm.)

Previous research has supported the value of using news media, films, and literature for bringing alternative cultural perspectives into the classroom (e.g., Alderman and Popke 2002; Aspaas 1998; Bascom 1994; Cromley and Bilokur 1999; Macdonald 1990). Much less attention (if any) has been devoted to the potential usefulness of interviewing as a pedagogical tool. If conducted properly, an interview can provide students with a direct and personally invested means of building intercultural awareness. As pointed out by Shepherd et al. (2000: 286): "Communication across national boundaries could help to dispel narrow, stereotypical, or hegemonic constructions that are still pervasive in teaching materials." Discussing the need for bringing alternative voices into the geography classroom, Berry (1997: 283) noted that "[f]irst-person accounts can crystallize issues, relationships, and experiences of students." The act of listening to each other, while largely neglected in education theory, is an important pedagogical device for building democratic and tolerant citizenship (Welton 2002).

From a more practical perspective, carrying out an interview may assist students in developing communication skills needed for the workplace (Hindle 2000).

This interview exercise contributes to cultural understanding because it involves a dialogue between international and American- born students and encourages self-reflexivity on the part of the student-researcher. Self-reflexivity implies that the research is not about dispassionately looking at an "other" culture, but instead, through the research process, understanding how our own cultural "baggage" shapes our views and prejudices (Crang 1998). The ultimate \value of the interview lies in how the cultures of interviewer and subject come together, allowing American-born students to reexamine their own society and redefine the borders of their own cultural frame of reference.

Assigning students to conduct interviews also offers the instructor an opportunity to discuss ethics, particularly the importance of enabling people to decide voluntarily whether or not to participate in the interview. This ethical and administrative process is called informed consent. Informed consent not only involves obtaining permission to conduct an interview, but also requires the interviewer to treat participants with respect and make sure they understand the nature of the research and the risks and benefits of their involvement (Vujakovic and Bullard 2001). For teachers, introducing the issue of informed consent is useful for discussing the interview as social practice, or how interviewing is influenced by power relations between the researcher and the research subject (Herod 1993).