January 1, 2001 - AMA: Notes of Peace Corps Physician Robert Davidson in Malawi (Part II)

Peace Corps Online:

Directory:

Malawi:

Peace Corps Malawi :

The Peace Corps in Malawi:

January 1, 2001 - AMA: Notes of Peace Corps Physician Robert Davidson in Malawi (Part II)

Notes of Peace Corps Physician Robert Davidson in Malawi (Part II)

Notes of Peace Corps Physician Robert Davidson in Malawi (Part II)

Who Am I, and Why Am I Different?

by Robert Davidson, MD, MPH

"Hey Daktari, they need you over in medical right away." This, thankfully, pulled me from a staff meeting on budgets to take care of a volunteer who had been assaulted and had a head laceration. The story behind this unfortunate event started me thinking about the subject of diversity in Africa.

The volunteer was a 25-year-old African American woman. She had been in downtown Nairobi on a Friday and happened to be near a mosque as the mid-day prayers finished and a group of men emerged into the street. She was wearing a hat that she had purchased in Africa, one traditionally worn by men of the Islamic faith. Several of the men approached her and started shouting to her to take off the hat. One of them grabbed it from her, and she got into a tug-of-war with him. She began yelling for him to stop and leave her alone. One of the other men picked up a board lying nearby and struck her over the head causing the laceration. As she let go of the hat to defend herself, the men ran off shouting back to her that she needed to learn her place. She was not badly hurt and was not knocked out. She got a ride to our office holding her head to stem the blood flow. After calming her and anesthetizing the laceration, we had the chance to talk as I cleaned and sutured the wound.

As we began to talk, the tears swelled in her eyes. "Doc, this happens all the time. Who am I and why am I different?" In my best open-ended question style, I prodded her to discuss the problem openly with me. Out came a poignant story of why she had chosen the Peace Corps and her experiences as an American with dark skin in Africa.

She had grown up in a predominately black community, gone to a prominent university dedicated to the education of black Americans, studied African American history, and was looking forward to working in Africa with "her people." Her actual experience was quite unexpected. She came to realize that she was much less African and much more American than she had thought. She related the experience of talking with a group of educated Africans in the school in her community. She told them she felt she was having difficulty being accepted as a friend and colleague and asked them why. They responded that she was a "Mzungu." She was shocked. Mzungu is roughly translated from Kiswahili to mean "European." It has taken on a much greater connotation, however, and is applied in a semi-derogatory manner to refer to the colonialists from Europe and developed nations and is applied to all ex-patriots working in eastern Africa. It was a difficult realization for her that she had so much more in common with Europeans and with the other Peace Corps volunteers than with the Africans who looked much more like she did. She felt she was being discriminated against in Africa in a manner much more virulent than she had experienced in the United States as a black American.

A few days later, I was sitting in on a committee of volunteers called the "Diversity Committee" that had been formed to look at ways to attract a more diverse group of volunteers to Africa to better represent the many cultural groups of the United States. The same black American volunteer, stitches still in her scalp, addressed the group. I want to quote her as closely as I remember. "Diversity should not be a goal in and unto itself," she began. "If you work toward diversity, you are admitting that there is still discrimination. The goal should be to do away with any biases and allow true equal opportunity for all and then let what happens happen. I want to work with people who I care for and respect and who feel the same way about me. It has been very hard for me to admit that I am more comfortable working and relating with other volunteers, most of whom are white, than with the Africans I thought I identified with. I am also coming to the reluctant conclusion that I am probably better off as the descendant of slaves brought to America than I would be if my ancestors had remained in Africa. Do not get me wrong; I hate the whole idea of slavery more than anyone else does in this room. However, I am so glad that I have the opportunity in the US to accept people for who they are and not get hung up on the color of their skin."

As she finished, there was a stunned silence in the room. It had taken great courage for this young women to express her feelings openly with the group. She had become the teacher on what diversity is all about. It had taken pain and incredible insight for her to come to this conclusion. I left the meeting with a good feeling that we will continue to advance in the US in our understanding and intolerance of racism and bias. We will be led in this process by young women and men of diverse backgrounds willing to explore and express their feelings.

So what does this have to do with diversity in the medical profession? For 22 years before coming to Africa, I was on the faculty of the University of California, Davis, School of Medicine. For 12 of those years, I served on the admission committee. Each year the committee struggled with the issue of diversity of the incoming class. There was almost universal agreement among committee members that there was a positive value in having an ethnically diverse class. What we differed on, often precipitating lengthy discussions late into the evening, was what criteria we should use in the selection process. It was seductively easy to fall back on the objective data supplied by the MCAT and undergraduate GPA. How could we measure our success in achieving diversity? We talked in terms of overcoming barriers as a measure of accomplishment, diverse language skills, and commitment to underserved communities. For some applicants, these notions helped us to see their potential value as future physicians and to secure them a place in the entering class. However, this did not address the applicant from a minority race or culture who was not disadvantaged. If diversity itself was the goal, we should give preference to all members of a minority race or culture. It is clear that we were not seeking diversity alone, but the added value brought to the education process and to the future profession of a class that reflected the rich cultural diversity of California.

Just as the young black American volunteer's experiences enriched all of us, a diverse profession can do the same. She was able to define the meaning of diversity in a way that was impossible for someone who had not shared her experiences, and she was willing to impart this to the group.

We would not need to worry about the concept of diversity in the profession if the opportunity for admission were equal among all. The goal is finally doing away completely with bias by race or ethnicity. Then, as the volunteer said, "Let what happens happen." We are not there yet. We must continue to work toward this goal and, in the interim, be willing to accept that diversity in the profession has an added value both in the education process and in serving our patients.

Daktari Bob

The Modern Plague

Robert C. Davidson MD, MPH

I have been in Eastern Africa for 1½ years. It has taken me this long to come to grips with the staggering global and personal impact of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa.

Accurate statistics on the epidemic are hard to come by. The reporting system is getting better, but probably still under-reports. The United Nations Agency on AIDS [UNAIDS] provides the most comprehensive data. Their January 2001 data estimate a total prevalence of 25.3 million infected people living in sub-Saharan Africa, an estimate that represents 80 percent of all HIV+ persons in the world. The new case rate for 2000 was 3.8 million, down from 4 million new cases in 1999. In 8 countries in the region, at least 15 percent of the adult population is infected with the virus. Botswana, where the prevalence is estimated to be 35.8 percent of the adult population, has the worst statistics. The statistic that strikes me hardest is the estimate that 1/3 of all 15-year-olds in sub-Saharan Africa will die from complications of AIDS. The infection rate in teenage girls is 5 times higher than in teenage boys, although the boys begin to catch up during their 20s.

The economic impact is catastrophic. Sub-Saharan countries spend about 2-3 percent of their gross domestic product [GDP] on HIV / AIDS, in spite of the abysmal lack of treatment opportunities for most HIV+ Africans. The total spending on health in these countries averages only 3-5 percent of GDP. Dollars spent on HIV / AIDS tend to go for treatment in the later stages of the disease process. In Kenyatta Hospital in Nairobi, a large public hospital run by the government, 40 percent of all occupied beds are devoted to treatment of HIV / AIDS patients. In Burundi, that figure rises to 70 percent of the beds in the Prince Regent Hospital in Bujumbura. Since the disease strikes hardest during the working years, the loss of manpower extracts a heavy toll on the country’s economy and productivity. UNAID estimates that in South Africa, as the disease progresses in the infected population, the total GDP will be reduced by 17 percent, which amounts to $22 billion (US) wiped out of the economy annually.

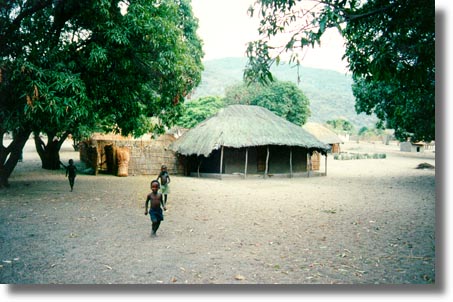

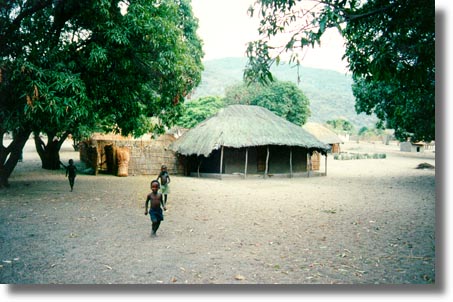

The personal suffering is immeasurable. No one is unaffected by the impact of a family member, neighbor, or friend who has the disease or has died from it. The Peace Corps volunteers report a funeral a week—at least—in most villages, with the causes of death avoided in hushed tones. A walk through any African village on market day is a sobering experience. Emaciated women try to sell their wares while succumbing to the wasting process of AIDS. Men with oral thrush, thin arms, and probable dementia stand idly by. The elderly, who passed through their sexually promiscuous years before the epidemic, seem to take on a larger daily role. The specter of the children is the most horrific. Thin faces with no hope in their eyes stare at life passing them by. The number of orphanages dedicated to abandoned children is growing. The traditional tribal family structure is overwhelmed and can no longer take in additional children from relatives who have died or are dying.

As I see it, there are 2 reasons that the epidemic has gotten so far in sub-Saharan Africa. One is the virulence and effect of the virus on the basic body defense system. The multitudes of infectious diseases that abound in Africa make immuno-compromised persons easy targets. The more important factor, however, is the nature of transmission via sex. Many cultural beliefs and practices in Africa contribute to the easy transfer of the virus through sex. As I listen to rural men talking, I become aware of some of these beliefs. For example, many believe that if a man has sex with a virgin girl, he will be cured of the disease. Women are much more vulnerable in this culture. The process of improving their status and rights has only begun. Many men still believe, as did their fathers and grandfathers, that it is a man's right to have sex with whomever he wants. Women are often looked upon as property. The dowry or payment to the woman's family or tribe "buys" the women for the man's family. If the man dies, a brother or other man of the husband's family can then claim the woman. Women have little capability to resist the sexual advances of the men of the community. Thus, the 5 times higher rate of HIV infection in teenage girls.

There Is Hope

In spite of the huge economic impact and human cost, there is hope. The human spirit is amazingly resilient. I recently attended a “conversion” party at a Nairobi orphanage. Children born to HIV+ mothers carry the mother's antibodies to HIV and therefore test positive, although they may not be infected with the virus. As they clear the maternal antibodies, they sero-convert to negative status, and the nurses and caregivers celebrate. There are some encouraging signs that inroads are being made on the disease. In Uganda, often referenced as a country on the right track, the estimated prevalence rate of HIV+ persons was down to 8 percent in 1999 from a peak of 14 percent in the early 1990s. Most African governments now acknowledge the AIDS epidemic and support or at least allow prevention programs. Billboards, TV commercials, and hastily drawn signs promoting use of safe sex practices abound. The strong oral tradition in Africa expresses itself in effective messages from traditional community theatre. Such theatres are increasing in number and influence.

There are things that can be done. In Uganda’s success story, 2 two factors contribute to the reduction in new cases. The first and more important is the growing acceptance of condoms, now readily available in the most remote villages, and the continual message from media and oral tradition messengers re-enforcing their use. The second factor is the increasingly availability of low cost, community-based testing centers. The development of these centers was supported by international aid money. Its donors were smart enough to use community groups to develop and run the testing and counseling centers. The contrast between the lack of hope in villages in Kenya and the heartwarming support and optimism displayed in the community testing centers in Uganda is impressive. I really do not think the epidemic will be stopped in Africa until an effective vaccine is found. In the interim, however, there is much that can be done.

Treatment Dilemmas

The HIV / AIDS epidemic presents several treatment dilemmas. A major controversy exists, for example, regarding the use of anti-retroviral drugs. They are readily available in Africa, but at a price far beyond most people’s ability to pay. If the struggling government health systems tried to buy the drugs needed, even at so called "cost," it would literally bankrupt the system and probably the country. One can argue on the side of a moral imperative to treat, but the reality is quite different. A better use of money for medications would seem to be the relatively cheap antibiotics available to combat and help prevent the secondary infections. Readily available generic antibiotics would go a long way toward reducing 2 of the biggest killer infections: TB and pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP). The retro-viral drugs could best be used in reducing HIV transmission from mother to infant through maternal treatment prior to birth. Pre-natal retro-viral treatment could reduce the infection rate in newborns by an estimated 50 percent.

Breast feeding by HIV+ mothers is another dilemma. It is known that breast milk carries the virus. The rate of untreated maternal-child transmission of the virus in Africa varies from 25-45 percent depending on the population. This is much higher than in industrialized countries where the untreated rate is estimated at 15-20 percent. US studies have shown that breast feeding by an HIV+ mother raises the risk that the child will be HIV+ by 14 percent. Two studies in Africa have shown that breast-feeding raises the rate of children who are positive to 50 percent. On the other hand, if the child does not breast feed, then he or she is exposed to the numerous bacteria and parasites in the usually untreated water supply. Several studies have shown as high as a tripling of the infant death rate in children who are not breastfed. The current WHO recommendation recognizes this dilemma and advises HIV mothers to breast feed their babies for 6 months and then wean them from breast milk. This seems like a reasonable compromise.

In no way do I mean to minimize the effects and suffering in the US from the HIV virus. However, the impact on daily life is of such a greater magnitude in Africa that it is incomprehensible without actually being in the center of it. To paraphrase Yoda of the Star Wars series, "There is a grave disturbance in the galaxy." We all must find some way to contribute to combating this modern plague.

Daktari Bob, [AKA Robert C. Davidson MD, MPH]

"You gotta keep a sense of humor"

Robert C. Davidson MD, MPH

The past month has been busy and difficult. It included my third autopsy and death review of a volunteer. I used to try to attend the autopsy of patients I was caring for, inasmuch as I always learned from the pathologist. Autopsies in Africa are quite different. Since most hospitals do not have refrigeration, the autopsy is done as soon as possible. The morgue area is small, relatively unventilated, crowded with bodies on the floor awaiting something, and hundreds of relatives on the lawn outside standing vigil until the body is released to the family. As I sat under a beautiful flame tree outside the morgue awaiting the arrival of the pathologist, I watched this incredible tableau unfold. One family was singing a kind of mournful chant as they awaited release of the body they had come for. The doors opened and a very regal looking gray-haired African man walked out with the body of a small child wrapped in dirty linens. The rest of the family with much wailing and crying followed him. He showed incredible dignity and poise as he slowly disappeared down the dirt path leading away from the morgue carrying his dead child. My heart cried out for him. Shortly after this, an old pickup arrived, its bed filled with men. It backed up to the morgue and loaded 3 crude wooden coffins, lashing them on top of a metal rack. The men piled back into the truck bed under the coffins. Then this whole retinue started off down the dirt road swaying from side to side as if it would tip over from its load at any minute.

Finally, the pathologist arrived and we proceeded into the autopsy room. Because there was an ongoing police investigation into this death, 4 detectives and 2 police photographers accompanied us—too many people for the small autopsy room. The pathologist whispered in my ear, "Don't worry, they won't last long." He then chuckled and nodded for his assistant to begin. Sure enough, in a scene right out of the old television series about Dr. Quincy, medical examiner, one by one they began covering their mouths and quickly exiting the room. Soon there were only the 3 of us left. This significantly reduced the tension in the room, and I had the opportunity to talk with the pathologist about his work in Africa. He had a great sense of humor, and I realized this was his way of coping with his gruesome job. That evening, as I reflected on the day, I realized how important humor was to me in the way I dealt with the stress of the job and living in Africa. I decided to share some of the humorous things I have encountered so far in hopes that it will bring a chuckle to the readers and lighten their stress a bit.

As I exited the plane on my initial arrival in Nairobi, I was of course a bit anxious. It was about 10:00 at night, and I was scheduled to be met by a driver. As in any airport, taxi drivers, people wanting to carry my luggage, and others offering to obtain whatever I wanted, immediately accosted me. In the midst of this jumble of bodies, a voice with heavily accented English asked if I was here with the corpse. No, I replied, I was not here with the corpse. Off he went to look for someone else he was to meet. I was finally able to get across to the group that I did not want any of their services or products. I did not see anyone, however, who looked like my driver. I began formulating plans to change some money into shillings and figure out where I could spend the night. The same man came back and asked again if I was here with the corpse. Again, my reply was no. As he started away from me, I heard, "Well someone got to be here for the peace corpse." I suddenly realized that the pronunciation of corps was different in Swahili, and I was indeed here for the corpse.

The differences in English have led to several other humorous events. Early in my tour, I went to one of the major hospitals we use for volunteers. As I was given the grand tour, I was repeatedly introduced to Sister this and Sister that. I remarked to the Peace Corps nurse who was with me that I did not realize this was a church-run hospital. No, this was a private hospital she replied. Why then, I asked naively, were all the nurses nuns. When she recovered from her laugh, she began my education in British medical jargon. Nurses are called sister and charge nurses are matrons. When I asked to see the emergency room, she looked perplexed until it dawned on her that I meant the casualty ward. But the best was yet to come. I was caring for a young volunteer with a pilonidal cyst that needed surgery. I arranged with our surgeon to do this in the outpatient surgery. I then told the volunteer to be ready, as she was booked into the theatre at 10 a.m. the next day. She got this frightened "no way" look on her face until I realized that she thought she was going to be on stage for a large audience with her bare posterior displayed for all.

Some of our best laughs have been with the workmen hired in Nairobi for various jobs. I am sure there are some very skilled workers in Kenya, but we do not seem to get them. We live in a lovely 40-year-old colonial home. It has lots of character, but, like all older homes, it has lots of problems. For instance, the roof. It seems to have a roving roof leak. After each rain, we dutifully call the landlord with the news that, yes, the roof leaks again. He sends out his trusty work foreman who inspects the house and proudly states that the roof leaks. He will schedule the men to fix it. The next day, a worker arrives to patch the inside ceiling plaster and repaint the ceiling. I try to suggest gently that he might want to fix the roof first. No, he is the painter. Another man will fix the roof. Of course it rains before the roof fixer has a chance to come. Back comes the painter with his plaster and paint. Again I suggest that the roof be fixed first. He ignores this advice and again repairs the ceiling. My wife reminds me that he gets paid to fix the ceiling and if it keeps leaking, he gets more work. Finally, the roof man comes. He proceeds to cut off some branches from trees in the area to make a ladder of sorts. After a period of loud noises on the roof, he exclaims that the roof leaks. He will come back later to fix it. In the meantime, it rains again. My wife bakes some cookies for the painter-plasterer. At last count, we have had the roof man 4 times and the plaster man 7 times. Yesterday, we had a heavy rain and of course had to get out the buckets to catch the drips through the ceiling. Actually, we are looking forward to the upcoming visit by the kindly painter- plasterer.

Perhaps the best story is the saga of the paper truck. A large truck was loaded with paper to be taken to the recycling plant. The paper was piled way too high, making the truck top heavy. As it started up the hill on a busy street near our house, it hit a deep pothole and the axle broke. It was already leaning heavily to one side with the weight of too much paper. The workers decided to try to repair the axle on site. They jacked the truck up and set it on rocks so they could work on the axle, then enlisted about 10 men to hook ropes to the uphill side of the truck and pull on them to keep it from tipping over down the hill. Meanwhile, frustrated drivers were making new pathways over adjacent lawns and winding through the men holding the ropes. We were enjoying watching this spectacle when it began to rain. Of course the paper was not covered and began acting like a sponge soaking up the rainwater. This made the truck even more top heavy and it soon began to tip. Their answer was to get more ropes and men to counterbalance the load. The crew grew to about 20 and might have worked if the rain had only gone to the paper. However, the clay dirt road soon became a slippery mud bath. I do not think even the best of the Hollywood comedy writers could have envisioned this scene. As the day progressed, the paper continued to get heavier, the truck tipped more, the road became more slippery, and we were now up to about 30 men with ropes. Finally, the law of gravity won out and the truck slowly began to tip. As the workers and rope men realized what was happening, they all abandoned their posts and ran uphill. As if in a slow motion film, the truck slowly tipped over and began its roll down the side of the hill. The next day, another truck arrived and the paper was hand carried up the hill to be carted away to the recycle mill. The new truck swayed from side to side with too much wet paper raising its center of gravity.

When the strain and frustration of living and working in Africa (or anywhere) begins to get your down. "You gotta laugh." Those are my words of advice for the month.

Daktari Bob, [AKA Robert C. Davidson MD, MPH]

"You're Doing What?"

That was the response I heard most frequently when I told my colleagues at the University of California, Davis, School of Medicine that I was leaving to go to work for the US Peace Corps in Eastern Africa. After the initial shock, and a few questions about where and how my wife and I would live, there was unanimous support for the decision. Frequently, a colleague would say, "Wow, I would love to do that." I was tempted to say, "Well, why don't you?" but realized that a decision like this was not and should not be made on the spur of the moment.

The "why" question was and continues to be the hardest for me to answer. I had a great job at U.C. Davis. I enjoyed teaching medical students and residents and my practice through the Family Medicine center was successful and interesting. However, I had a growing feeling that I had lost, or was losing, the desires which pushed me into medicine as a profession in the first place. I was just a bit too comfortable. I missed the feeling of commitment and job satisfaction that I had when I started my career working in an OEO (Office of Economic Opportunity) neighborhood health center in a barrio section of Los Angeles. I needed a challenge.

For you to better understand my comments,

I need to tell you a bit about what I am doing. On February 1, 2000, I began working for the US Peace Corps as the Area Medical Officer for Eastern Africa. I am a hired employee of the US government, and need to emphasize that the real heroes of the Peace Corps are the volunteers who dedicate 2 to 3 years of their lives to working in countries where they are needed.

My primary responsibility is the health of the volunteers who are working in Eastern Africa. I cover an ever-changing area that currently includes 5 countries: Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi, Madagascar, and Uganda. The area expands or contracts as the political climate changes in the nations of Eastern Africa. Ethiopia, for example, had one of the larger Peace Corps activities before the recent political unrest and destabilization resulting from its conflict with Eritrea, another previous Peace Corps country. When the safety of its volunteers can no longer be reasonably assured, the Peace Corps closes down in that country until things settle a bit.

Each Peace Corps country has a medical office as part of the core support for volunteers. For the most part, advance-trained nurses and/or physician assistants staff these. The area physician serves as consultant, mentor, and quality assurance person, and fulfills a host of other duties for the country medical staff. There are 4 area physicians in Africa, their areas roughly determined by dividing the country by the 4 points of the compass. We use regional hubs such as Johannesburg, South Africa and Nairobi, Kenya, for treating volunteers who need levels of care greater than that available in their countries. We can, and do, send volunteers back to the United States on med-evacs when they need levels of care not readily available in Africa.

The clinical aspects of the job are fascinating.

A misguided and somewhat cynical colleague said before I came that all I would see would be healthy 20-year-olds with sexually transmitted diseases. He could not have been more wrong. I have seen more pathology and interesting health problems in the first 6 months than I would see in years back in the States, even at a major medical center like the U.C. Davis Medical Center. The majority of problems can be roughly divided into 3 categories: stress-related disorders, infectious diseases including tropical diseases, and trauma. I will talk more in the future about some of the tropical diseases we see and some of the inherent problems in trying to avoid them. Much time and effort are spent in preparing the volunteers to avoid health problems "in country" and stay healthy. For the most part this preparation is effective.

However, I have seen a number of unexpected health problems that are initially diagnostic dilemmas, especially without the ready availability of modern imaging techniques now standard in the United States. One such dilemma concerned a 40-year-old woman volunteer whose disorder was ultimately diagnosed at George Washington University Medical Center as a pericardial thymoma. Another case involved a 62-year-old man with cancer at the esophageal-gastric junction. In a recent case, a young volunteer complained that his "belly button" hurt and was pushing out. Examination showed a huge peri-umbilical abscess, which drained 200 cc of foul-smelling, probably anaerobic, pus. He responded well to incision, draining, and antibiotics. My impression is that the base problem is a congenital non-closure of the embryologic vitello intestinal duct that has been asymptomatic up to now. He is winging his way to Washington, and I am sure the surgery residents will enjoy and learn from caring for him.

The Peace Corps volunteers today are far different demographically from their counterparts in the early days of the Corps. The age of the volunteers in my area ranges from 24 to 74, with a large number in their 50s. They bring with them the usual diseases for their age cohort. No longer is a diagnosis of type II diabetes, asthma, or hypertension a cause for rejection from Peace Corps service. What has not changed is the wonderful sense of dedication and challenge that has always motivated volunteers to select Peace Corps service. I have enjoyed all the patients I have cared for, but the sense of dedication and commitment I find in the volunteers makes them special.

Before I make this job sound like Nirvana,

I need to put our living situation in perspective. The Eastern Africa hub is Nairobi, Kenya. This is where we live. Nairobi is no longer an easy place to live. Many people who lived here in the past speak fondly of the "good old days" when Nairobi was considered a great place to live. Certainly the weather is wonderful and the scenery is spectacular. Nairobi is a cosmopolitan city with fine restaurants and modern shopping centers and supermarkets. However, the constant threat of robbery makes it difficult to relax. United States nationals live in virtual fortresses complete with iron bars on the windows, wrought iron security gates on all doors, a wrought iron security grate to isolate our sleeping quarters from the rest of the house, perimeter security lights, and 24-hour security guards at each compound. We carry a radio link to the US Embassy at all times for use in an emergency. Home invasion robberies, street muggings, and the more recent trend of car jackings detract considerably from enjoyment of the city.

More recently, the 2-year drought has produced severe water and, therefore, electricity shortages. On alternating days, we have no electricity from 6:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. or from noon to midnight. Water availability is variable. Most homes have plastic tanks to store water, but to be of much value these require electric pumps and electricity. One becomes so dependent on modern appliances in the US that the transition to kerosene lamps and 2-burner gas ranges for cooking seems like a hardship. But it certainly offers the opportunity to return to a simpler way of life. I have found it fun to do puzzles by lamplight, and easy to adjust to a sleep schedule from 8:30 p.m. to 4:00 a.m. so I can have a couple of hours of electricity in the morning.

I am not quite sure how my reflections

on working as a physician in Africa will be received by my colleagues and medical students. My experiences are far different from those of the many US physicians who give of their time and talents in the many mission hospitals in Africa. Yet it is certainly helpful to me to reflect on this experience, and perhaps by sharing it with you I can help you contemplate why you chose medicine and what you want from your career. In future segments, I will talk more about my impressions of the health problems in the host countries and of the medical care systems and physicians in Eastern Africa. I will also try to give some personal thoughts and observations as a US physician practicing in Africa. For now, I need to sign off before the electric.i.t.y.. g.o.e.s... o.u...

Robert C. Davidson MD, MPH

Stopping for Death

Physicians are faced with death in its many varieties throughout their careers. There is an undefined socialization process which takes place during the training years in medical school and post-graduate training. This is necessary to provide the capability of continuing to function with death all around. However, we sometimes feel we are exempt from the emotional toll that death extracts from us. Several events in the past month brought this home to me and I would like to share them with you.

2001 Gets off to a Bad Start

The new year began on a decidedly bad note. On December 30th, a Peace Corps volunteer from one of my Eastern Africa countries was killed in an automobile accident while on holiday in a South African country. Because the death occurred in the area covered by my colleague based in Pretoria, I was spared the necessity to travel there and take charge of the death review that includes an autopsy. I began to make plans to travel to her host country to assist with grief counseling. This was the first death in my area, and I reviewed the protocol developed by the Peace Corps on what to do when a volunteer dies. Unfortunately, this review was prophetic of another tragedy that pulled me into a series of extraordinary events.

One week later, on a rainy Sunday afternoon, I got a call from another of the Eastern Africa countries I cover that a volunteer had been critically injured and was probably dead. Could I come right away? I told them I would come as soon as possible and to have the nurse in the medical office call me as soon as she knew the details. The next available flight was not until Tuesday morning. We forget the luxury of frequent flights between the major cities that we enjoy in the States. The country nurse called back that evening that the volunteer was dead and had been killed by an elephant. "What! An elephant! How did it happen?" "We do not have all the details. You will need to get these when you get here." No one else was injured but a friend observed her death. We went through the details that would need tending to since we all wanted to be able to transfer the body back to the States as soon as possible. The country nurse would arrange for the body to be brought to the capitol and arrange for a host country pathologist to perform an autopsy with me.

The In-country Morgue and Autopsy

On Tuesday morning, we went to the morgue at the public hospital. I had been warned by more experienced medical folks in Eastern Africa that the handling of bodies in this area of the world was quite different. I felt like I had been through enough in thirty years of medical practice that I could handle anything. When I arrived at the morgue, I was surprised to see two to three hundred people arranged around the building. My driver explained that tribal customs required that the family stay with the body until burial. I thought there must be several bodies in the morgue or a very large family. The morgue building consisted of two rooms. One was a body holding area and the other a room for autopsies. The body room was completely full of stacked bodies so the overflow of bodies lined the corridor and the walls of the autopsy room. Some of the bodies were still in their clothing, but others in the clothing they were born with. There was no refrigeration or even air-conditioning. The odor was predictable. All the windows in the autopsy room were wide open for ventilation. I felt like we were center stage in a theater in the round as all the relatives were sitting outside looking in through the windows.

The pathologist was very helpful. He had gone to medical school in Africa but did his post-graduate work in Great Britain. He apologized for the room and bodies but said the laws of the country required a release from the authorities before an autopsy could be done or a body released. I asked if we could drape a sheet over at least the two closest windows. He laughed and said, � yes.� He agreed that an autopsy on a white body would attract a lot of attention. The autopsy itself was relatively easy. There was no mystery about the cause of death. There was massive blunt trauma to the thorax and abdomen with a flail chest, ruptured left apex of the heart, bilateral hemo-thorax, a huge liver laceration and a ruptured spleen. We both agreed that microscopic examination was not necessary, and he signed off the cause of death to allow us to start the process of getting the body released for transport to the States. Meanwhile, I was charged with writing up the autopsy and getting the facts surrounding the death.

Her college roommate was visiting the volunteer. They had hired a driver and car for an animal safari in one of the National Parks. About 10:00 in the morning, they came across a herd of elephants near the road. They stopped to watch and take pictures. The driver warned them to stay in the car. After some minutes, the elephants started to move away and the two young women got out to get some better photos. After they moved about ten meters toward the elephants, a large female, probably with a young elephant ward, charged. The volunteer was knocked to the ground and the friend and driver related that the elephant then kneeled on the body and rolled back and forth. This is apparently how elephants kill. The story was consistent with the autopsy findings.

After the Emergency, Stopping for Death

The rest of the week was taken up with government releases, securing a hermetically sealed casket for transport, and arranging for transport of the body back to the States. We had several sessions with the staff and other volunteers for grief counseling. I was impressed with how the country personnel handled this very difficult situation. A counselor was sent out from Washington to assist the process. She was very helpful. She asked how I was holding up and of course I said I was fine. She then pushed me to describe the autopsy and surrounding events, and it all came flooding out. Tears are therapeutic, and I was getting therapy. As strong as we feel we are as physicians, situations like this extract their toll. It is ok after the emergent situation to be a human. To grieve. To cry. To be angry. If you ignore this human need, it just builds up inside. I am convinced after all these years that we in the profession do not do enough to support each other. A colleague who takes the time to listen and allow the physician to reduce their guards and talk about feelings provides a very important service.

When I got back to Nairobi, there was an e-mail awaiting me from one of my medical student sons. He is in his third year and currently assigned to the trauma surgery service at a large urban public hospital. He had just experienced his first intra-operative death that happened to be a police officer. He described how he did not even think about it during the surgery. As he left the theater after it was all over, he noticed that the lower part of his scrubs below the gown were blood soaked. He laughed that now he knew why they wore rubber boots. As he headed toward the locker room, he realized that some of the police officers were staring at his legs and the blood. The reality of what he had just been through and the impact on the lives of the officer's family came pouring over him. I felt so helpless on the other side of the world. I wanted so badly to be there to let him vent. I want him to retain his humanity. I can only hope that one of his colleagues will let him vent and provide an atmosphere that it is ok to be vulnerable as a physician.

Daktari Bob.

Nairobi, Kenya

"Please Help Me. My Baby Is Sick and Needs Medicine!"

Before coming to Eastern Africa, I was repeatedly warned about "culture shock." We have been fortunate to enjoy a fair amount of international travel and had lived for a time in Central America. I thought I was ready. Most of the transition has gone well. I am even learning a little Swahili. Against the advice of the Regional Security Officer for the US Embassy, we elected to not live in one of the secure compounds of clustered townhomes that house mostly Americans and personnel from other embassies. Instead, we selected a lovely older home on a two-and-a-half-acre plot.

Kenyan Asians and African Kenyans

The neighborhood has very nice homes, many of which are owned and occupied by Kenyan Asians. These folk are third or fourth generation Kenyans who culturally continue to relate to India. The are the descendants from the Indian railroad workers brought into Kenya during the British colonial rule. They have prospered in Kenya financially, and "Asians" own many of the larger Kenyan companies. It seems curious that after three or four generations they still do not identify themselves as Kenyan. We have enjoyed our conversations with our neighbors and have frequently been given advice by them, particularly on how to interact with "Kenyans." It has been more difficult than we thought to relate to "African Kenyans." We have a great relationship with the Kenyan staff at work, both the professional and clerical staff. We have had some wonderful discussions about America. At our Fourth of July party we all toasted our common heritage of rebellion against British rule. However, the rest of the Kenyans with whom we have daily interaction are at such a different income level that it is difficult to be friends or even friendly.

The Most Difficult Cultural Adjustment We Have Faced

The level of poverty and unemployment in Nairobi is so high that we are constantly made aware of the disparity of resources. "Please help me. My baby is sick and needs medicine." This plea came from a woman in rags sitting on the street outside our home with a baby asleep on the dirt. Perhaps the easiest thing to do would be to give her some shillings, which might make me at least feel a little less guilty. However, we are repeatedly warned by other expatriates and our Asian Kenyan neighbors to give nothing to beggars. They will return ten fold the next day, we are told, if the word gets out that the "daktari" gives money. Perhaps some examples will help portray the dilemma.

We interviewed for a man to help with housework and driving. "Lucas" was selected. He had a pleasant personality and came with good references. However, very soon problems began to arise. Lucas was repeatedly absent for several days at a time due to illness. He came to see me at home on a weekend and asked me to get him some medicine to cure him. I asked if he had seen a doctor. Of course, the answer was that he could not afford it. He then proceeded to take off his shirt to show me a rash that was bothering him. As I gazed at an emaciated body with a typical Herpes Zoster rash, I suspected immediately the problem. This man was in the latter stages of AIDS. In a future segment, I want to talk about the impact of HIV/AIDS in Africa. The physician part of me began to race through options. How could I help? I knew I could not be his physician. I did not even have a Kenyan medical license. He could never afford retro-viral drugs nor even lab tests and preventive therapy such as Sulfamethoxa-zole/trimethoprim. I began to worry that his cough might be more than a simple problem. Could he be spewing mycobacterium on my wife as he drove her around in the car? My mind returned to an incident the previous week when he had presumably fallen asleep while driving and almost went off the road. I of course knew he could no longer work for us. I was not worried about his infectivity, but rather his capacity to do the job. We sat on the porch and talked for a long time. He seemed to understand that he could not work any more for me but began bargaining for some money so he could go to the doctor, get cured and find another job. I simply could not say no. I gave him one month's salary as terminal pay and some extra money to go see a doctor. We left on good terms.

The next day he was back with his daughter in her school uniform. "Please, I need some money to pay my daughter� s school tuition or they will kick her out. She wants to be a doctor like you." As hard as it was, I held the line on what I had already given him and assumed this ended the saga. The next day his wife showed up toting a small baby. "Please daktari, Lucas is very sick and will die if you do not give him some money for medicine." My heart went out to this woman. Was she also HIV+? Was the baby? How could I justify sitting on the porch of this beautiful home saying no to her? On the other hand, where would it stop? This is one of the dilemmas of "giving" in Kenya.

Institutional Need

Recently, I visited a mission hospital outside of Nairobi, staffed by rotating American physicians under the auspices of their church. The chief surgeon, an orthopod from Atlanta, immediately took hold of me and urged, "Come with me. You have to see something." He led me to the bedside of a precious 10-year-old Kenyan girl. She had been brought to the hospital following snakebite. He had operated to remove necrotic tissue from the area of the bite and relieve the tremendous pressure from swelling. However, she was showing increasing systemic manifestations of the venom. In his opinion, if she did not receive anti-toxin within the next 24 hours, she would probably die. Did the Peace Corps have any? How about the US Embassy? Could I help him? My mind began to race. Yes, I knew that we stocked a shared supply of anti-venom with the US Embassy medical office. It was for use on Embassy personnel or dependants or Peace Corps volunteers. The words from my orientation sessions came ringing back. "Under no circumstances are you to treat or give medicine to any person other than authorized US personnel." This was the General Counsel for the Peace Corps speaking. My boss, the director of clinical services for Peace Corps and a general surgeon, leaned over and whispered, "You better listen to this as you will be tempted." The speaker went on to outline the dire consequences which could ensue if we "misused" US property. OK! I can handle this, I mused. However, standing in a mission hospital a world away from Washington, looking at a little girl that I could probably help from dying, was not part of the bargain. The US spent millions in aid to Kenya. How could I justify not "giving" to this little girl and this caring and dedicated physician?

The Harambe

The harambe is a long-standing cultural custom in Eastern Africa. It has been explained to me that it comes from the tribal custom of helping other members of the tribe in times of need. During my first week in Nairobi, one of the staff said there was a harambe for one of the secretaries and I was invited. Great, I thought. It is nice to be included. It turned out that it was not a gathering at all. Rather, it was a memo to all participants telling them how much they "owed." I have always been supportive of the graduated income tax, but wow, this was a pretty hefty bill. I paid the money, mainly because I was new in country and did not know what else to do. I did not have a very good feeling about it. Sure enough, the next week I was invited to another harambe. Was this the spirit of giving I wanted? Where would it end? Was I being selfish for wanting a bit more personal involvement and control over my gifts? Would I be culturally insensitive if I did not join in this "long standing Kenyan tradition"?

I could cite more examples, but I think these give a good picture of the dilemmas faced by an American physician in Eastern Africa. I purposely did not say how I decided to respond in these situations. The issues are more important than my responses. I do not view my working here as a "gift" to anyone. I am supported well by the US Government through the Peace Corps, and I am gaining much more than I am able to give through my work as a physician. I do feel a desire to "give" in the face of the huge need I see in this country. We are slowly finding what works for us, but if you are faced with the same situation, expect the decisions to be harder than you think.

Happy holidays!

Daktari Bob

Some postings on Peace Corps Online are provided to the individual members of this group without permission of the copyright owner for the non-profit purposes of criticism, comment, education, scholarship, and research under the "Fair Use" provisions of U.S. Government copyright laws and they may not be distributed further without permission of the copyright owner. Peace Corps Online does not vouch for the accuracy of the content of the postings, which is the sole responsibility of the copyright holder.

This story has been posted in the following forums: : Headlines; COS - Malawi; Special Interests - Medicine; Special Interests - Peace Corps Physicians

PCOL2349

07

.

I'm USA citizen foreign trained general physician.

I'm intersted to work with peace corp in Africa or Middle East.

Iwas born in sudan and got my medical education in egypt and trained in both sudan and Egypt.

I'm looking forward hearing from you

Thank.

Dr. Ibrahim Gornas

Tel: 612 -378 -0754