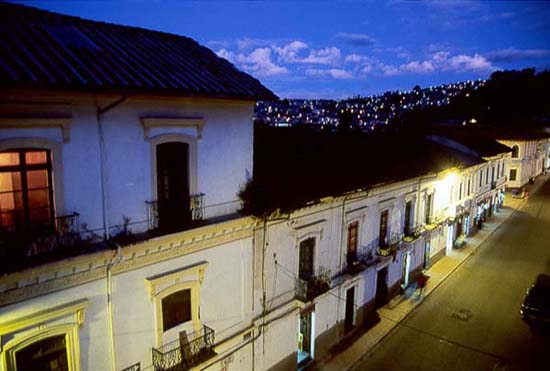

Peace Corps Volunteer Moritz Thomsen's "Farm on the River of Esmeralds"

"Thomsen’s Peace Corps experience has left him with a belief that modern farming techniques can be the salvation of third-world farmers..."

moritz thomsen: howls from a hungry place

part II - the farm on the river of emeralds

Read part one: Living poor

Moritz Thomsen ends his first book, Living Poor, on a vague note; not really knowing what do to once his Peace Corps duty comes to an end in 1968, he simply leaves the town of Rioverde, spending an unsettling last few weeks in the town he had hoped to transform three years earlier. "My last weeks in Rioverde was punctuated by screams," he writes in his last chapter, as well as goodbyes to those who had long since given up viewing the gringo as a novelty, and a final, slow unraveling of the cooperative he had worked to form in the little fishing town. So, too, does it appear that his ties to Ramon Prado and his family (wife Ester and baby daughter Martita) unravel: "But as I stepped off the porch to leave, Ester screamed, and I turned to see her, her face contorted and the tears streaming down her cheeks. We hugged each other, and Ramon rushed from the house and stood on the brow of the hill looking down intently into town."

Thomsen’s exit from Rioverde itself proved to be a lasting one, but he spent not even a full year back home in his native Seattle, Washington before he was back in Ecuador looking to keep a promise he made to Ramon: to come back and buy a farm with him, and to work as equal partners. He chronicles the first six years of their tumultuous partnership in his second book, The Farm on the River of Emeralds, published originally in 1978. He mentions his father Charlie in passing once again—"my father has just died, I have ten thousand dollars in my pocket"—and just as quickly the elder Thomsen is dropped from the narrative. The plan seems so simple: Thomsen provides the money and know-how gleaned from his years as a pig farmer in the States following his service in WWII; Ramon, a much younger man than Thomsen (who has just turned 53) provides the toil and guides the old gringo in the ways of the Ecuadorian jungle; on a deeper level, Ramon is to play the son to Thomsen’s new role as cranky elder, together to forge a new life on their own terms. They find a farm on the Esmereldas River ("River of Emeralds") and grin through their terror as they agree to buy it and enter into "that most delicate and intimate of relationships—a business partnership."

"Now we had it," Thomsen writes of the sprawling jungle farm, "or it had us."

And in no time at all Thomsen’s dreams of living peacefully as an equal to all around him, brought back to life by a perfect relationship—Thomsen as teacher and the young, fully alive Ramon as pupil, living an idyllic existence in the finest tradition of "the brotherhood of man"—crashes down around him. A cast of characters materializes from the jungle, ready to join Thomsen, the lone gringo, and Ramon, with his pregnant wife and young daughter. He finds himself once again a subject of curiosity among the locals; they come to him for jobs, treating him as the new patron or "big daddy," unable to fathom the idea that Ramon, a black man like them, seemingly as poor as they, could really be half owner of the huge farm, an equal to the strange white man who has come to live among them. The ensuing struggles for power and respect and survival drive Thomsen’s book through to its explosive conclusion six years later.

Each chapter of Farm on the River of Emeralds centers on these characters. "The People of Male" is about a sort of conglomeration of local men (boys among them as well, although in poor societies you don’t find "teenagers," just sickly infants and toddlers who seem to one day skip ahead to full, wounded adulthood). They just seem to come with the property at first: "They mistook our pity for weakness, or perhaps they thought we were so stupid that we found them indispensable," he writes. At first they drive Ramon and Thomsen crazy with their laziness and ineptitude—Thomsen often creeps up on them only to find them napping in the fields surrounded by orange and banana peels, or they see him coming and the whole group suddenly erupts into a slashing, frenzied blur of machetes and axes. He can’t always bring himself to fire them, though; rather, he ends up hiring many of their sons and brothers, and begins to see not just laziness in their work habits:

"Yet, watching, I began to grieve for them, for they were still under the illusion of their power to direct their own lives, lost in the magnificence of the newly awakened awareness of their own manhood, lost in their dreams of how they would conquer life. How modest their expectations and, in this brutal land, how impossible to fulfill. I knew they had no future; they lacked the opportunities and the inner discipline to do anything but end up like their fathers. Have you ever watched a little herd of lambs as they frisk and play in the slaughterhouse corral? …Watching them, one forgave them everything—they were so trapped, so doomed. On the weekends it seemed relatively unimportant that they were impossibly lousy workers."

Thomsen is learning, and fast, that applying "middle-class North American standards" to the culture of poverty he is now smack in the middle of makes no sense whatsoever, and will serve only to alienate him further from his neighbors:

"O.K., so the worker doesn’t work very well because he eats so badly. O.K., so out of desperation a man steals. Now it gets complicated and confusing. How can this poor worker who suffers so from malnutrition dance for twelve hours straight or, on Sunday afternoons, play futbol [soccer] with such fierce sustained enthusiasm? Why does the thief like as not end up in the local salon, dead drunk from the sale of your radio or his neighbor’s chickens?…And now that worst and most delicate of questions, which made the head reel, Wasn’t it possible that the man who stole your radio actually regarded you as his friend?"

It’s probably no coincidence that Farm on the River of Emeralds often reads like a war narrative—Thomsen served as a bombardier on a B-17 squadron in the European theater in World War II—and it was a war with many fronts. His equal partnership with Ramon is cause for many heated, painful exchanges; at the same time they must present a united front to the local workers, who bring their own battles and demands to the farm. Thomsen’s Peace Corps experience has left him with a belief that modern farming techniques can be the salvation of third-world farmers ("I had wanted to stun the province with twentieth-century technology…that modern system of that uses fifteen times more energy per acre than a farmer in an undeveloped country."), a belief that dissolves in the face of monsoon-like rains, failed crops, non-existent markets, and the intractable mindset of desperately poor people, the "Walking Wounded" of a full chapter.

In that and other chapters Thomsen singles out individual members of the tragedy/comedy unfolding around him: "Dalmiro", an "old, white-haired, toothless, barefoot, wrinkled, wreck of a man" with a raging libido and a disturbing habit of getting shitfaced drunk and urinating on the other workers as they slept; "The Brothers Cortez," a "package deal" of four brothers who both exasperated and mesmerized their long-suffering bosses; "Santo and the Peanut Pickers" recounts perpetually horny Santo and his Quixote-like quest for love ("With Santo, love was everything, habit nothing. Wasn’t this perhaps his greatest virtue, that he refused to accept and live with stale and exhausted emotions? And wasn’t this perhaps his tragedy?").

Thomsen’s writing is filled with foreshadowing, as well as visions that border on mystical, but perhaps what really defines his style is the use of shattering epiphany. His life was filled with them—moments of absolute, terrifying clarity that destroy whatever perceptions he clung to in order to survive, and setting the course for the next stage of his life:

"There are certain days in life so packed with horror or revelation that if you survive them your whole past stand rendered, the essence so distilled and clarified that it is impossible to keep on deluding yourself. In the revelation department one thinks of those religious conversions that strike one down like lightning, turning drunkards or thieves into missionaries. Days of revelation are the mileposts in life at which one makes ninety-degree turns or puts a bullet through one’s head or murders one’s wife or loops back violently, seeking again in the innocent past what had gradually faded away and made existence chaotic or meaningless."

One such experience leads him to join the Peace Corps in 1964—a twenty-four hour stretch during which he finally sees his California hog farm is doomed, finished; he has to put down his beloved dogs, sell his pigs, shut down the farm where he is already reduced to living in an unheated tool shed, and stand for the first time in a room filled with his butchered hogs: "I had fallen under the malevolent eye of God, and He had more tricks up His sleeve. I didn’t know if I could take any more that day, but I remember thinking, ‘It’s coming, whether or not you can take any more, and it’s coming today." It comes, all right, when a cow is dispatched right in front of him by a grinning slaughterhouse employee. As far as Thomsen was concerned, he was every bit as finished. A Peace Corps commercial on television that night put an idea in his shorted-out brain; it must have looked like a modern-day Foreign Legion: "Spewed out of that deadening rural life, screaming with rage and self-pity, as bloody and battered as a new born child, I was given another chance at a brand new kind of life."

The revelations didn’t stop once Thomsen left the United States; his first book, Living Poor, is filled with them. But Thomsen was a man of incredible stubbornness, a trait he applied to his belief that he could change the world in true Peace Corps fashion, and one after the other, he finds himself facing up to awful, shattering truths about his convictions. One that nearly does him in in Farm on the River of Emeralds comes in "Victor," a chapter near the end of the book on one of their most beloved (and ultimately disappointing) employees. Finally faced with the naked truth that Victor has been robbing Ramon and Thomsen blind, Ramon fires him, kicks him off the farm, shattering the façade of harmony they both had valued enough to turn a blind eye on Victor’s betrayals. It’s the last straw, says Ramon, no more Mr. Nice Guy; the people for miles around steal from them and see that nothing is done and damn the reasons for their thievery or desperation, he’s going to do something about it. Ramon rejects their new ideas for how to run a farm, asking, "do you know how they control the stealing?" at a large coconut farm up the river. Thomsen knows: "Every year they shoot a few thieves right out of the trees." Thomsen watches Ramon as he leaves for his house that night:

"How he had changed since I first knew him, how hard and sad and stubborn his face. I thought of those two ultimate sins, the two unforgivable sins against life: to murder and to be poor. Poor Ramon. It looked like he was moving toward that awful moment when he would have to commit the first one to get saved from committing the second."

It never comes to that in Farm on the River of Emeralds, but the change in Ramon and the disintegration of his partnership with Thomsen loom large in the final chapters. As with Thomsen’s other books, this one raises far more questions than it could ever pretend to answer. Thomsen demonstrates that he is one of those unfortunate souls who must constantly seek out reasons and motivations—what is it that makes a man steal pennies from your pockets as you sleep or punch his wife in a drunken rage or slash his neighbor with a rusty machete? But what Thomsen does best is observe what it is that leads to the way the dramas unfold around him, not taking the outrages and constant thievery and disgraceful behaviors he writes about at face value, never taking the easy route.

Next month: "Howls From a Hungry Place" part III: The Saddest Pleasure: A Journey on Two Rivers and My Two Wars.

-- marc covert

Peace Corps photograph by Vernon K. Richey

archive index | current issue

©2002 Smokebox

a non-commercial, volunteer driven e-zine