Peace Corps Volunteer Moritz Thomsen's "the saddest pleasure: a journey on two rivers, and my two wars"

"When I stand before that old charlatan, God, am weighed on the scales, found wanting, and am hurled into hell’s fires, it will not be for those thousands of people that I killed, it will be that goddam egg..."

moritz thomsen: howls from a hungry place

part III - the saddest pleasure: a journey on two rivers, and my two wars

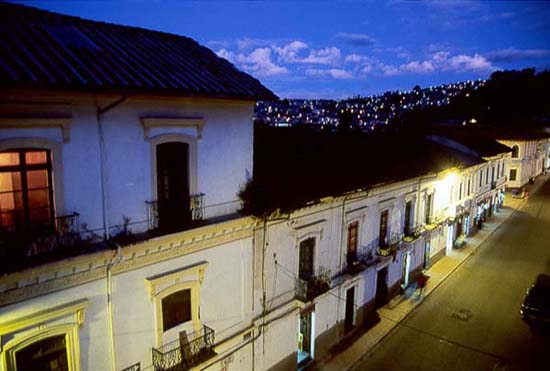

photo: alan mathison

Go to part one: Living Poor

Moritz Thomsen wrote his final books in the years after he left his jungle farm near Esmereldas, Ecuador. He made good on a promise made at the end of Farm on the River of Emeralds by buying a large tract of land across the river from the farm he shared with his partner, Ramon Prado, and attempted for four years to eke out an existence raising corn, tropical fruit, coconuts, and other failed ventures. Whatever intentions he may have had to free Ramon from his role as Good Son to Thomsen’s Big Daddy, the new farm’s location made it necessary for Ramon to come across the river by boat nearly every day to bring groceries, cigarettes, newspapers, any of life’s necessities that could not be raised on a remote jungle farm.

The Saddest Pleasure: A Journey on Two Rivers is a memoir written by Thomsen partly to tell the story of the disintegration his relationship with Ramon; for all practical purposes, he was a part of Ramon’s family, a grandfather to the Prado children, daughter Martita and son, Ramoncito ("Little Ramon"). Thomsen sets his tale as part memoir, part travelogue, and part devastating commentary on the rapacious practices of a capitalistic world bent on destroying huge chunks of South American society. The title is taken from a line in Picture Palace by Paul Theroux ("Which Frenchman said, ‘Travel is the saddest of the pleasures’?"); in fact Theroux wrote the Introduction to Saddest Pleasure.

Thomsen is sixty-three years old at the time of his journey; the year is about 1978 or 1979 (Thomsen’s style pays little attention to concrete dates, he makes you work to keep your bearings, and gleefully plays havoc with chronological order when it helps the narrative; he at least warns the reader in advance). He wastes little time in getting to the reason for his extended trip:

Ramon, my best friend, my partner, that jungle-wise black who was supposed to support me through the crisis of my sixties and at the end see me decently buried, had lost his nerve. He had driven me off the farm. The details were so outrageous that now, almost a year later, I still cannot bear to think about it.

…Kicked off the farm, I went to live in Quito…I found a small apartment with a view of a cement wall…I bought a bed, a table, and four plates, three more than I needed. How awful it was to be of no use to anyone, to awaken in the mornings and be unable to think of a single reason for crawling out of bed. One day out of desperation it occurred to me that finally I might make a trip.

The trip turns into much more than that. Thomsen, in his usual self-mocking style, downplays his relentless curiosity and love toward South America and its people, portraying his journey at first as little more than a way to take up time. But time soon becomes a heavy burden as it dawns on Thomsen that he is now an old man, and his sense of doom and impending death begins to close in on him as he notices the "invisibility" that his advanced age has bestowed upon him. Out in the airports and busy streets of South America, he is regarded as little more than just another old, white-haired gringo. But time spent waiting for flights or sitting alone in hotels and restaurants give rise to some of Thomsen’s most compelling writing. In one passage, he remembers a game of "The Worst Thing I Ever Did," played with friends in Quito around a large table:

I had to confess first and could tell without thinking back about a Halloween night when I was ten years old. A tiny white-haired woman had come to a door whose bell I had rung. …I had stood outside her vision and thrown an egg at her—heard it smash against her face—and rushed wildly away in horror and self-loathing. (Fifty-three years later I can still hear that dreadful sound; my flesh still crawls.) …it had never occurred to me mention instead an early afternoon in 1943 when I had led some groups of bombers to a now-forgotten German target where either three or thirty thousand people were reported to have been killed. I have truly forgotten both the target and the number of dead…When I stand before that old charlatan, God, am weighed on the scales, found wanting, and am hurled into hell’s fires, it will not be for those thousands of people that I killed, it will be that goddam egg.

Thomsen’s journey takes him to Brazil, and in Rio de Janeiro he is faced once again with the crushing poverty that pervades life in South America. Eating in a small restaurant, he is served a huge bowl of potato salad ("I order what I think is a tossed Italian salad"—despite some 15 years spent living in Ecuador, Thomsen still hasn’t quite gotten the hang of Spanish, and the Portuguese of Brazil is beyond his grasp). He pushes the half-eaten bowl away, and

…immediately a Negro who has been standing against the wall and made invisible by some large potted plants appears by the next table and with the fierce power of his concentration impales me with his look. He stares into the bowl of salad, brings one hand to his mouth, and implores me with the other hand, the palm up, open and vulnerable…I offer him the salad; he takes it and sits at the next table, hunched over the food, eating rapidly. We do not look at each other again for there is something unspeakable in that desperate hunger that lies between us like an accusation.

Walking in the street I consider with confusion that good feeling I had had at offering a hungry man my garbage.

Although it does not take place on this trip, Thomsen recounts a journey he made to Lima, Peru, years before. He sought out a church in that huge, sprawling city of eight million people that contains the mummified remains of Francisco Pizarro, the infamous Spanish conquistador, founder of Lima and conqueror of the Incas. Standing before the body, Thomsen took advantage of his opportunity to spit on the floor at the head of the glass coffin. He sees Pizarro as "the greatest capitalist the world has even known":

…and his figure, the eyes still flashing with avarice, still strides across the continent, across the world…The manipulators of technology are the new Pizarros; the directors of the multinationals are the new rulers of the world—nice men with gentle manners some of them, connoisseurs of wine, modern art, beautiful women…They are the most honored men, sharing the admiration of the world with the politicians whom they have bought off and who serve them…These guys may own the world, but they don’t control it: they are puppets caught up and driven ahead by the cresting wave of an incredible science that is way past their power to control: they are puppets blind to the consequences of their actions, alive only to the big chance. They are the bastards, these sober-suited Pizarros, who are going to kill us all.

The Saddest Pleasure is, like all of Thomsen’s published works, impossible to pigeonhole into any one category. What makes it such an important and powerful book is the far-ranging sweep of Thomsen’s ire as he rages against the powers that have been strangling all of South America for centuries. It’s tough going at times; dark, cynical, utterly stark in the hopelessness he sees in the future of that huge, complicated continent. It is writing that is heartbreaking in its timelessness—a book written during the early eighties and published in 1990, Saddest Pleasure is still right on the money in 2002. Ongoing drug wars; roving gangs of murderous thugs; huge tidal waves wiping out villages where most people don’t have two sucres to rub together; rioting and demonstrations over gasoline prices; hordes of refugees from neighboring Colombia; crushing debt unforgiven by developed countries or the World Bank; police corruption and brutality—things have not changed enough (for the better or worse) in Ecuador or South America to make Thomsen’s twenty-year-old writing lose its relevance:

Poor raped South America. We lie over her in a kind of post-coitus triste but beginning to feel the itch of a new engorgement. After Pizarro it was all so easy. We won’t roll away from her yet; she still has the power to enflame our lusts, and her feeble efforts to roll away from us strike us as being not quite sincere. She has not yet been raped into madness like her black African sister.

It is in The Saddest Pleasure that Thomsen finally brings to life one of the great, awful characters in non-fiction literature: his father, Charles Thomsen, himself the son of one of the classic "robber baron" characters of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century—Thomsen’s namesake grandfather, who made a fortune in the flour mill business in the Pacific Northwest. Did Moritz, writing in Saddest Pleasure, really see his father, dead since 1969, standing before a statue in some square, or walking out of a bar, or standing before him as he tried to sleep in the hot, Brazilian night? No matter, it helps the story—Thomsen’s writing is filled with mystical visions and shattering revelations—and in introducing Daddy he sets the stage for his last great book, the posthumously published My Two Wars.

The Saddest Pleasure was published in 1990, to mostly good reviews, but by that time Thomsen was a very sick man, 75 years old and suffering from the effects of a lifetime of backbreaking farm labor and a love-hate relationship (mostly love) with cigarettes. Spending the last 28 years of his life in the jungles of a tropical country didn’t help his physical state either; visitors (and there were many—curmudgeonly persona to the contrary, Thomsen was a gregarious man, easily driven to despair by loneliness or isolation, even if it was often self-imposed or brought about by his ability to wound deeply those who loved him most) were often shocked to find him, white hair falling out in clumps from fungal infections, teeth long gone, writing constantly and barely eating, just hanging on in Guayaquil, Ecuador. He died there on August 28, 1991, after contracting cholera and refusing relatively simple treatment that could have prolonged his life, albeit briefly.

He had seen the end approaching for years, and worked feverishly to complete two books (a third, From My Window, is reputed to have at least made it to the "taking notes" stage). Bad News from a Black Coast has languished on publishers’ desks for over a dozen years, excerpted once in Salon but otherwise unpublished. But he had also finished a manuscript documenting his battles with his tyrannical father, as well as his experiences as a B-17 bombardier in the European theater in World War II. My Two Wars is the result of those last years of feverish writing. The opening line, magnificent in its simplicity ("This is a book about my involvement with two great catastrophes—the Second World War and my father") sets the tone for what could very well be the best account of the experiences of American bomber crews in WWII. The inevitable comparisons to Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 don’t take away from Thomsen’s book at all.

But to get to WWII you must first clamber through the dark, riveting tale of Thomsen’s father Charlie. By all accounts a mean, cruel, repellent man, driven by a consuming desire to top his own father in amassing wealth, power, prestige—and perhaps most of all, the fawning, unquestioning sycophancy of his children—Charles Thomsen haunted his son until Moritz himself died. He had a daughter, Wilhelmina, Moritz’s older sister, and when both children were very young his marriage to Thomsen’s mother collapsed. His remarriage and building of a huge French Provincial mansion named Wildcliffe set the stage for an abusive, surreal family scene that left lifelong scars on brother and sister alike. (Wildcliffe is still there, near Kenmore, Wash., at the end of Lake Washington, now a bed-and-breakfast.)

Publishers and reviewers alike tended to shy away from Thomsen’s war with Charlie; at the outset it can seem that readers could not possibly be as engrossed with the father-vs.-son battles of My Two Wars as Thomsen was in writing about them. But the story of this domineering, hopelessly tortured man, and the shambles he makes of his own life and those of everyone around him, is integral to the story of Moritz Thomsen’s life. He never quite managed to put his father to rest, and never was able to forgive himself for sticking to the old bastard, remora-like, for no other reason than to avoid being cut out of his will (which almost happened anyway).

Thomsen had already been drafted into the Army for over a year when Pearl Harbor brought his relatively well-ordered life to a crashing halt. For all the abuse he endured from his father, the old man was rich, and Moritz spent his days as a young man skiing, camping, mountain climbing, fly-fishing, and attempting to screw himself to death whenever the chance presented itself. Even in the Army Thomsen discovered that he could volunteer for permanent KP and be spared the rigors of barracks life in exchange for endless potato peeling and pot scrubbing. But Pearl Harbor made him want to be a hero, and he entered the Army Air Corps, precursor to the Air Force, in hopes of becoming a fighter pilot. Years later, writing in his apartment in Guayaquil, he reflected on that day:

It was only years later that I understood the menacing quality of that late afternoon. It had about it an awful sense of a slumbering portentousness that emptied the air of life and continuity. It was like a gigantic stutter, an awful stopping of time, a hiatus that promised horrific changes. In a very real sense that day in December of 1941 was the true beginning of the twentieth century. That day the Depression was officially over, the ownership of America changed hands, bankrupt American farmers, the last symbols of an agricultural America built on the principles of Jeffersonian democracy, could now desert the land for five-dollar-a-day jobs in the war factories… December seventh was the last day that the country represented an ideal for which one might with dignity offer to fight and die. Ten years later it was no longer worth fighting for. Twenty years later, when three million farmers a year were going bankrupt and the Bank of America owned most of the farmland in California and you couldn’t raise tomatoes without a $150,000 harvesting machine, it was not even a country fit to live in. Unless, of course, you enjoyed working in a factory.

Ultimately Thomsen washes out of pilot school, relegated to the post of bombardier; the man who sits in the great plexiglas bubble in the nose of a B-17 and sights in on the target miles below, then releases the payload of bombs. From his seat perched above a Norden bombsight ("It was probably John Steinbeck who had popularized the belief that bombing with the Norden, one could drop a bomb into a picklebarrel from eighteen thousand feet. Perhaps our disillusionment began when…our practice bombs landing in little flashes of flames a thousand feet from the center of the target, proved to us that not only could we miss a picklebarrel but the factory that made them. Plus the parking area around the picklebarrel factory and the special railroad spur that hauled off the picklebarrels and the town where ten thousand employees slaved for the war effort making picklebarrels.") Thomsen was unfortunate enough to have a sweeping view of the fate of bombers around him, shot to pieces by German Messerschmidts, or blown to bits by the dreaded flak bursts from anti-aircraft guns.

He trains that same sweeping view on everything around him during the war—a devastated, weary London; drunken, hardened bomber crew members; the doomed innocents he recalls years after their deaths in the air over Berlin, France, or the English Channel; the dead members of his own crew. He took part in D-Day, bombing into the front lines of smoke as instructed, only to learn to his horror afterward that the lines of smoke had moved—the American Air Corps had inadvertently dropped bombs directly in the midst of American troops. The terrible guilt one would expect from a mistake of that magnitude is hinted at, but somehow soldiers thrust into positions that entail causing massive amounts of death and destruction must find a way to live with such guilt, or at least block it out. Thomsen addresses his own "survivor guilt":

To those of us who survived combat, who flew time after time and returned to the ordinary routines, routines that at first struck us as being miraculous—eating, sleeping, bicycling along the summer roads, drinking whisky in that absolutely exclusive group of combat airmen (pleasures that gave us less and less pleasure)—a slowly growing boredom with life began to be apparent in our conscious thoughts. We were touched with shame to be still living, to be doing the same banal things in the center of that encircling and invisible and growing pile of bodies. Why had we been unchosen? There seemed to be no way to be worthy of the dead without joining them; we were in competition with the dead who had left us, and left us filled with guilt. A passion to live. A passion to die. How could we reconcile these two emotions that kept rising in us, except in the way we did, by sinking into a kind of catatonia, an emotional hibernation that was like insanity.

When Thomsen finally reaches his quota of 27 combat missions, he waits out the remaining days of the war in Texas; after the Japanese surrender, he takes a 30-day leave to visit Charlie at Wildcliffe, pick up some clothes, odds and ends, and his beat-up pickup truck. What happens here as he goes from one just-completed war to the other, the one that would haunt him until his dying day, is a final outbreak of hostilities as he finds his father barely bothering to cover up the fact that Moritz ,the returning war hero, would have been of much more use to him dead than alive. Thomsen’s survival, he realized years later, was looked at by his father as little more than one more complication to spoil his "sunset years."

Thomsen spent the years from 1945 to 1965 running a hog farm near Chico, California, a venture that finally failed and led to his foray into the Peace Corps, and ultimately to his 28-year stay in Ecuador. Through all of his experiences, he felt a great passion for writing, and produced countless articles and essays for publication in newspapers and magazines, to some success. But his four published books were mostly a labor of his own "sunset years." All but Farm on the River of Emeralds are still in print; Bad News from a Black Coast has not attracted a publisher for twelve years, but Thomsen completed it probably just months or less before his death, so there is always the possibility of a fifth volume. Admittedly, Thomsen’s style can be a bit much for some readers—some find themselves turned off by a "self-pitying" tone, or uninterested in Thomsen’s hatred of his father or intense relationship with Ramon—but any writer who tries to express his rages and defeats and frustrations in life takes that chance. The fact remains that, to many fellow writers and a small, devoted cadre of readers, Moritz Thomsen is one of the truly great, yet unrecognized, American authors.

-- marc covert

archive index | current issue

©2001 Smokebox

a non-commercial, volunteer driven e-zine