Brian Wood lived as a Peace Corps volunteer in the town of Bilinga, in the midst of that cool, dark green tunnel

I noticed people looked nervous and unsettled. I asked a young woman sitting in front of me wearing a yellow and green paigne or wrap, what was going on. She responded by saying, "C’est une guerre a Bilinga!" A war in Bilinga? At war with whom? How can a small town in the middle of a rainforest be at war?

I noticed people looked nervous and unsettled. I asked a young woman sitting in front of me wearing a yellow and green paigne or wrap, what was going on. She responded by saying, "C’est une guerre a Bilinga!" A war in Bilinga? At war with whom? How can a small town in the middle of a rainforest be at war?

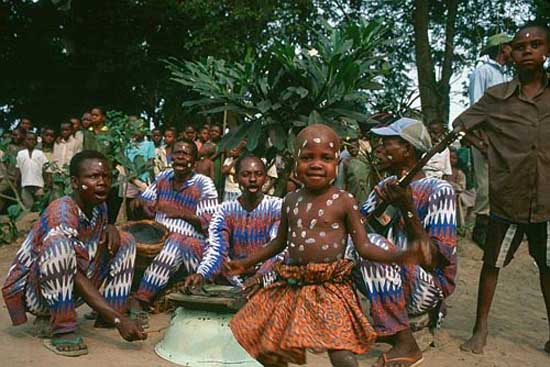

I was in the Mayombe rainforest in the southern Congolese region of Kouilou. The deep forest covers ancient mountains and hides many secrets in its rivers and swamps. I remember walking the small forest paths beaten by decades of men and women carrying the produce from their small plots deep in the forest. During these walks, the only company I would have the whole walk would be fluttering yellow, white, blue, and black butterflies. Sometimes the only sound that would beckon my ears would be the chatting of monkeys and chimpanzees or the cries of grey and green dots of parrots overhead.

There is another mysterious cry that snakes through the mist laden hills; the CFCO (Chemin de Fer Congo-Ocean) railway. This python of the Mayombe serves as the lifeline that unites the port city of Pointe-Noire with the capital Brazzaville 395 km east in the Congolese savannah. Brazzaville is the point where the immense Congo River opens itself up for navigation into the inundated forests of the north. The railway was built by the colonizing French in the early half of the last century to link the ocean to the river city. It is infamous for the huge human toll it took to build. An incredible number of Congolese lost their lives to the grand French project.

Today, the journey from Pointe-Noire to the nation’s third largest city of Loubomo (formerly Dolisie) can be a breathtaking experience. The Mayombe’s dominion is speckled with small towns and villages, chimpanzees, gorillas and many more inhabitants hidden by the protective drape of the forest. The Mayombe forms a dark green tunnel on the CFCO line; shadowed and cool with fleeting scents of honeysuckle pleasantly surprising the unsuspecting. The towering parasoleil trees always at the ready to shield one from the marching brigades of rain showers so common during the long rainy season.

I lived as a Peace Corps volunteer in the town of Bilinga, in the midst of that cool, dark green tunnel. My house was on top of a hill looking down to the station and out to the forest smothered hills in the distance. I used the train to go to Pointe-Noire for errands and to Loubomo to visit my closest friend, also a Peace Corps volunteer. The "roads" in the Mayombe were basically nonexistent especially during the rainy season. I remember taking a trip by Land Rover from Loubomo to my village taking us eight hours to traverse only 70 or 80 km. The CFCO was the only realistic form of transportation. This lifeline was at the end of its own rope, barely alive.

The railway functioned on the most minimum of scale. Trains were rarely on time and often about five hours late on a good day. Waiting is an art form in this region of Africa. A few deep frustrated intakes of air through the teeth and it stops annoying one after a while and becomes a cultural ritual, something to be admired. For me waiting opened up more time to think, observe, talk, and just be more aware of my surroundings. The causes of the artistic delays were numerous. Broken down engines, the all too common derailments, and fallen trees blocking the tracks in the forest were the major culprits. There was another increasingly common incident that just did not fit into the routine of derailments and fallen trees - the Aubervillois.

The name sounds very sophisticated when first uttered, but it conjures up sinister acts of terror in the Congolese who depended on the CFCO for their mobility. The name, Aubervillois, was just a sound to me before Christmas 1994. To this day I still cannot be certain who the Aubervillois were or still are. As far as I could tell, it was a gang of discontented Congolese men who were furious with the government and terrorized the frayed railway. Their thinking was that if you stop the lifeline you stop the capital and thus the country. The Aubervillois equaled terror up and down the railway. I recently read that the name Aubervillois was the appellation of the presidential militia – something very different than what I witnessed. The truth has a funny way of splitting itself when you are not really part of the place and space, as I was in Bilinga.

My collision with the Aubervillois was when I was on my way back from spending Christmas Day in Loubomo with my friend. We were just stationed at our respective posts and I snuck up to surprise him for the holiday. We were not supposed to visit each other so soon after posting, but I eagerly disobeyed. My friend was very relieved and we enjoyed an equatorial Christmas comforting each other after a very stressful first two weeks alone at our posts. I don’t remember the details of our Christmas because the events that followed took over my memory of that hot holiday reunion.

I was stealing my way back to Bilinga undetected by my surpervisors in Brazzaville when the Pointe-Noire bound train stopped in the Mayombe town of Mpounga. I was not surprised to be temporarily stranded here. This town was near the entrance to the Mayombe and often the trains were delayed for one or two hours on account of fallen trees deeper in the forest. When this sort of thing happened, we just usually practice the art of waiting without much complaining until the train starts again. After three hours, I knew something else caused the stop. Even on the CFO a three-hour delay at one station was a little much. I wondered what was really going on further down the line. I started asking.

This was when I heard the now internally famous words, "C’est la guerre a Bilinga!" More information materialized as the hours passed. Bilinga was being attacked by the Aubervillois. The train was held up in Mpounga to wait it out. Even waiting for wars is part of the art. The station in Bilinga was in chaos it as the center of battle. We learned there have been at least fifteen people killed from reports passed from station to station. The Aubervillois were punishing the town for a past resistance to their offensive. Apparently my town is volatile and fights back. Needless to say I was terrified at the prospect of eventually returning to Bilinga.

After learning the basic news of what was transpiring down the line, everyone on the sweltering train melted out and waited outside along the tracks. A kaleidoscope of women’s paignes brightened the clay embankments of the town. Once outside I noticed I was the only white person (mundele) on the overcrowded train. While sitting along those tracks, battling an eternal war of their own with the encroaching forest, there came over me an almost existential "C’est la vie en Afrique" feeling. Mpounga is hilly with houses and small banana orchards on many levels. It looked like the town was hanging; like dim chandeliers from the forest canopy. I was certain every shade of green called Mpounga home. It was the closest to the European fetish of the idyllic that I have witnessed. As I was looking at the absolute beauty of this poor train town in the rainforest, I noticed that most of the passengers looked worried but they had the air of just going along with whatever was happening. No matter what was happening, flies needed to be batted away and babies had to be comforted. I kept imagining every one of them looking at me and saying, "This happens, so just deal with it – we all do." I respected that and it actually helped me in this particular situation and many more after this. But once my thoughts were away from the Gaugin-esque painting of the town, the realization that there were gangsters with machetes and guns killing people just three stops away in another idyllic scene refocused my attention

The time came to board the train and head toward Bilinga. I did not know what to do. Should I stay here in Mpounga until the next train from Pointe-Noire comes? Should I just chance it and go home? Should I continue on past to the next town of Bilala where my Congolese counterpart lived? I decided to ask the same young woman what would be the best thing to do. Since the passengers seemed to know how to "deal with" unimaginable problems and circumstances, I thought asking her would make more sense than going on my very foreign and confused instincts. She advised me to continue on to Bilinga, assuring nothing would happen to me. She explained that because I am a mundele and American no one would harm me. America is seen as something heavenly – a paradise just as a tropical rainforest world is paradise to many Americans; a type of mutual imbrication born of the colonial project. Both views are very romanticized but I believe it made things a lot easier for me as someone who caused notice in this particular situation. I believed her and decided to head home to the war zone. The caravan then started on the nerve-racking journey to the center of the Mayombe. I felt like a refugee going in the dangerously wrong direction.

The train approached Bilinga station. The violent horde was still writhing as we pierced its combative core. It was not over! I do not know why the train started again toward Bilinga if the assault was still alive. Everywhere around me passengers were becoming more frantic. The normally relaxed and rolling Kikongo language became staccato and tense. The young woman repeatedly stood up and sat down not knowing what to do. She had every reason to be terrified. The Aubervillois have been known to murder and rape on the CFCO.

I saw wide, frightened eyes all around. Outside I could discern only raised machetes and guns through the many arms and heads grasping for a view. The Aubervillois and the citizens of Bilinga were doing battle just outside my window. Again I thought of not getting off and continuing to Bilala. The young woman yet again assured me that I would not be harmed if I descended. She used the same disorientating yet comforting reasoning as before; I am an American mundele. Trusting my young female seatmate, I decided to leave my refuge from the past five hours

Before I could get off, the Aubervillois invaded the train. I will never forget the image of hooded men with machetes running through the aisle. Their heads were covered by what looked like rice sacks with just the eyes and mouth cut out. They were dressed like any normal Congolese with t-shirts, old heavily worn slacks, and flip-flops on their feet. The young woman proved right. The villains trooped by without even a glance at the mundele American. No brutality was witnessed, but I do not know what happened after they went past our car. Who are they? What do they want? Those questions have never been answered.

The next few minutes were quite surreal. I do not remember hearing anything - just visions. I got off and had machetes and guns waving everywhere around me with bagged Aubervillois and uncovered townspeople in battle all around me. Somehow I just meandered through the crowd of combatants and peacefully, like a sleepwalker, glided up the hill to the sanctuary of my house – literally above it all.

I arrived shaken by the whole experience and in a sort of stupor. I did not feel safe in Bilinga and made arrangements to retreat to Loubomo as soon as possible. New Year’s was nearing and I feared for a repeat of the mayhem below.

The next train did not come until that night flooded with travelers stranded in Pointe-Noire from the morning’s stoppage. I boarded, but almost suffocated from only a few minutes aboard. It was not only the lack of air but also the density of bodies; a suffocation of darkness. Suffocation was a common death on the CFO. I had to get off. I exited through angry yells telling me a rich mundele should be in first class (first class was virtually the same). I was soaking wet with my sweat and others’. I conceded to stay another night at my hilltop home with my neighbors, the Mpouki family. I slept very lightly fearing an Aubervillois would break into my house and kill me in the night. I survived to the next eerily quiet morning.

That morning I awoke in a misty nether world. The mist covered the surrounding hills and nothing could be heard except for occasional automatic rifle shots. I walked out of my house and saw figures silhouetted by the forest veil. These figures were not the Aubervillois but the government military sent from Pointe-Noire (Bilinga and many other small towns and villages had no police force). The soldiers were dressed in the universal fashion of military green, berets, and automatic rifles forever attached to their bodies. I heard occasional automatic gunfire throughout the morning from the surrounding forest. I assumed the military was hunting Aubervillois stragglers. Everything was quiet and calm in a paranoid sort of way. The heavily armed security force did not make me feel any safer than the events from the day before. Another fact I learned living in the Congo was the real military is as much to be feared as any other gang.

I finally boarded that day’s more spacious train back to Loubomo. I told my friend what happened and called the Peace Corps office in Brazzaville telling them what had happened and that I was staying in Loubomo for the New Year’s holiday. After a few days, I went back to Bilinga where everything seemed back to normal. In fact, most of my days in Bilinga were rather routine and peaceful except for the occasional witch burnings.

© Brian Reed Wood

February 2002

Brian Wood" woodkoiwa@hotmail.com

Brian is now teaching in Japan and will be writing about that country in the near future.