Atidekate is an organization created by RPCV to assist community development in Ghana

Hello and thank you for visiting our site!

As many of you are probably keenly aware, "development" is a word of nuance, an opportunity for hope but also a curse, a word entangled in the religions and politics of our world. As such, the other officers and I have spent a large amount of time discussing what we represent as a legal entity and what we hope to accomplish through the creation of Atidekate. I felt that as the president, it might help the dedicated visitor to understand our vision more clearly by more intimately describing the origins and goals of this organization.

We are all Returned Peace Corps Volunteers (RPCVs) who have served in Ghana. Although we do not explicitly limit ourselves as such, it is that experience that has catalyzed the creation of Atidekate. In fact, the afore-mentioned conversations on what development "is" first started during that service, when we were sweaty, often mildly feverish volunteers trying to both learn about and implement development practices in our assigned sites. There is nothing like an unsatisfying workday to drive a volunteer to a bottle of beer (or stronger) and a heated discussion on what the heck we were doing there anyway.

All of us in Atidekate finished our tours (of two or three years) with a number of similar thoughts: a.) It was time to leave and we were ready to leave, but just when we were actually getting the hang of things. b.) We could have used more money for our projects, and we wanted to keep working on those projects. c.) We struggled, but left with a strong belief in the positive role of development. d.) The Ghana experience was too much to completely leave behind.

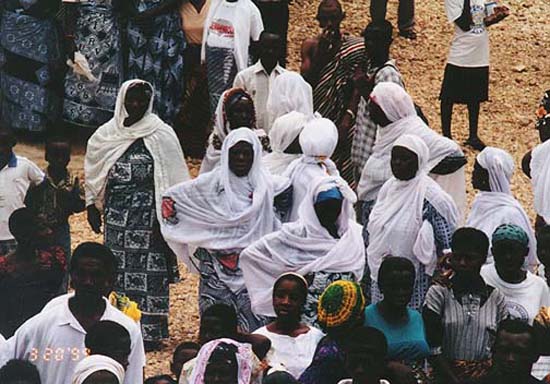

I am going to go out on my own now, and describe some of my own personal feelings about these four ideas. First of all, Ghana is an amazingly complex place. Government officials and linguists have strong debates on how many languages exist in the country; reasonably there are somewhere between 50 and 100 distinct languages and dialects in a country roughly the size of Great Britain. In this sense dialect doesn't mean a strong New York accent, it means an almost unique way of communication that can only be completely understood by its native speakers. I lived within walking distance of three different dialects in an area (southeastern Ghana, in the southern Volta region) that, if you look at our language map under <general information>, has been labeled as simply, "Ewe."

I use this example as a way of explaining what living in a village really means. The social rules are different, the politics are different, the food is different, the way you do everything is different. And complicated in ways that we as Americans don't expect them to be complicated. As a volunteer, I committed social faux pas in every possible way. I used the wrong hand, I greeted in the wrong direction, I implied things that I didn't mean to imply, I gave presents to the wrong people, I didn't give presents to the right people, I talked to the wrong person about a project, the list goes on and on. But I learned and after three years of effort, I tended (not always) to do things right for a change.

Someone who comes to Ghana for a week or two can see the beauty of the place, and maybe they can also find personal meaning in the visit, but if they say they understand what they experienced or what they saw, they are fooling themselves. There is a point, at about nine months for myself (I suspect many other RPCVs will understand what I am talking about here) where you one day wake up and realize that the community attitude about you has changed. You are no longer the foreign curiosity, no longer the guest, and so therefore might be expected to exhibit a social skill or two. It is at that point that I truly realized what a bumbling, moronic fool I had been and how much I still had to learn, just to tread water in a sense, just to be an average Joe. I don't know how else to describe it except to say that it isn't about smiling a lot, being especially courteous to everyone, or telling the chief how much you respect him. It is way more sophisticated than that. Perhaps that experience is indicative of my social skills but I still think anyone who has lived in Ghanaian village for more than a few months will understand.

So it is my opinion that expats, diplomats and your general yevu (the word for foreigner in Ewe) in a Land Cruiser or Land Rover may understand big picture issues but has no clue when it comes to the life and times of a particular village. Which, also in my opinion, is the reason that after decades and decades of ribbon-cutting, official ceremonies, and big plans, not that much has really changed in Africa in a raw, average yearly income and likelihood to live a prosperous life kind of sense. Ghana, and I assume sub-Saharan Africa in general, happens at a small-scale level, at the village.

Which gets me to the second, third and fourth thoughts that we all had, about believing in development and wanting to continue with the villages in which we lived. I left feeling that I had finally gotten somewhere, finally had all engines firing. Actually that is what I felt deep down; what I felt at a more shallow level was that Ghana was wonderful, but that I needed a break from the malaria and wanted to move on with my educational goals in graduate school. Once I had recovered though, and my stomach, liver, brain and skin were all functioning normally again, I wanted to get back at it. I wanted to stick with development, but this time do it right. Plus I missed the friends I had made in Akatsi and Abor and didn't feel comfortable with the thought of, "Oh well, it was nice knowing them. Hope they get on O.K." I won't go into detail about what I got out of the Ghana experience as a human being, but it was... transforming.

So I emailed Brendan Best, a volunteer and friend who had served down the road, then KC Choe, and soon Melissa Brown and Billy Hwang were in on the deal. Luckily enough they wanted to stick with it too, and we started discussing what kind of organization we should create. You might have noticed my tone earlier in the essay, but to be polite, I'll just say that we felt that there were lessons learned and improvements to be made on what we had previously experienced.

Generally speaking, we wanted communities to take the lead, tell us what they wanted, not vice versa. For that reason, we decided that we weren't going to limit ourselves to one kind of project, because that would in reality be a de facto decision for the villages. We are therefore creating action plans by asking individual communities about their goals and how they expect to attain those goals. We come in to the picture, practically speaking, by finding funds for projects created by communities to attain community goals. Each community has a variety of goals, in education, potable water access, and youth services for example, and we work with those communities to determine the most realistic funding strategies. Our first two projects, the school blocks in Abor and the youth center in Taviefe, are both community-initiated and we are looking for funds to help them complete the work that has already been started.

We also felt that to ensure the highest probability of success, we should take advantage of our individual, village experiences; in other words, work with people we know, trust and love. Atidekate then, works in villages where state-side, there is someone that "knows the ropes" of that community. These individuals are at the moment, all RPCVs, but in reality the organization is open to others, perhaps Ghanaians now living in the U.S., to take a leading role in maintaining contact with a particular village. This decision was particularly convenient, considering that in the first place, we were starting the organization to continue working in our own, individual sites of service.

One last point deserves mention, because along with the individual experience aspect of this organization, it is a particularly salient indicator of from where we are coming and of what makes this non-profit strong and unique. We saw a lot of waste and a lot of inefficiency, organizations using over half their budget to pay salaries to people to shuffle papers and hem and haw. Most everyone had the right spirit, but there were not a few Ghanaians who told me enough with the presentations, animations and activations. Where was the money? They had specific problems with specific solutions, all of which needed funding, and they needed money handed over. But then there was the Ghanaian side of the problem.

As part of a campaign by national news organizations to never say a positive word about Africa, I am sure everyone who reads this already knows about the corruption and graft that goes on. And it's real. But it isn't guaranteed and it most often occurs in black-hole type projects. Projects where grandiose plans are instigated from afar in large 4WD vehicles by people speaking foreign languages. Projects where managers try to snuff out graft with complicated directives, rules and large binders full of the latest development theory.

We've lived in the villages and we know who steals and who doesn't. Or perhaps steal isn't the right word. Like the time I left money for roofing timber to finish the school office in Dawlo, but which was instead spent on a hospital visit and malaria medicine for the carpenter's dying child. Atidekate will use at least 90% of all donations towards the actual implementation of community projects; in the case of our first two projects, building supplies will be purchased.

In August, Atidekate will take all collected donations (minus what we spend on paper-clips and envelopes) to Ghana, where we will assist the purchase of construction material for the first two projects in Abor and Taviefe. We will be in the villages to see the projects first-hand, double check financial accounts and record progress; at this time we will post pictures and assessments of accounts to our website so that visitors will be able to see for themselves where their donations go. Atidekate officers have made the commitment to visit projects that we sponsor because it is vitally important to us to maintain the financial integrity of this organization.

This will be the first step for Atidekate, but only the latest of many for its officers. It is the continuation of relationships complicated by the north-south divide. And in a world filled with the negatives of war, pollution, and social disparity, we are operating Atidekate as chance to do something positive.

Signed,

Augustus Vogel, President