Sierra Leone RPCV Martin Puryear's "Ars Poetica"

Martin Puryear's "Ars Poetica"

Dec 1, 2001 - Art in America Author(s): Koplos, Janet

A traveling exhibition of Puryear's sculptures from the last 12 years emphasizes materials, craftsmanship and abstract form-a timely reminder that these elements themselves can give meaning and relevance to art.

Above and opposite (detail), Martin Puryear: Ladder for Booker T. Washington, 1996, ash, 36 1/2 feet long. Photos this article, unless otherwise noted, Katherine Wetzel. Courtesy Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond.

Over the course of his career, Martin Puryear has periodically made reference to black historical figures. The Western scout and explorer James Beckwourth was named in the titles of several sculptures of the 1970s, and the most eloquent piece in Puryear's current 12-year retrospective, curated by Margo Crutchfield for the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and now traveling, is Ladder for Booker T Washington (1996).

This extraordinary work seems equally object and image. It is immediately recognizable as a familiar form, if of unfamiliar proportions: this ladder is 36 feet tall, and it narrows from about 2 feet wide at the bottom to little more than an inch wide at the top. The ladder's side rails are made from a tree that Puryear felled on his property in upstate New York. The peeled and split trunk tapers elegantly but twists and sways idiosyncratically to the side, front and back, declaring the particular history of its growth.

The ladder's round rungs swell at the center and narrow at both ends. The rails gather power from their dual irregularity: one seems to underscore the other in a tandem rocketing race toward heaven. At the same time, the work conveys a feeling of vulnerability because it is suspended in space: four sets of barely visible wires hold it away from the floor, walls and ceiling in its long, sloping climb.

The Virginia Museum, which used this work for its posters advertising the show and on the cover of the catalogue, included supplementary labeling for the piece on the two-story open stair landing it occupied as if made for the site. (It could be viewed straight on from the rotunda lobby, and also from the landing at the lower level and from second-floor balconies both in front of and behind it, for an unusually full range of viewpoints.) The text panel noted that there is some controversy associated with Booker T. Washington-who is today often seen as having encouraged Negro achievement only in the areas that did not threaten white power-and suggested that the extreme narrowing of the ladder symbolizes unreachable heights.

The suggestion is quite reasonable. Yet Puryear never comes closer than this to any explicit theme in his work. He has, as an artist, been far removed from the identity politics that has preoccupied many other black artists of his own and younger generations (he was born in 1941). In fact, this work is almost the exception that proves the rule: the rest of the show, like Puryear's art in general, cannot be identified with a movement or message, a theory or even an image. His sculptures evoke the summary viewpoint of Archibald MacLeish's famous "Ars Poetica," that "A poem should not mean/ But be." Puryear's sculpture does not mean, it just is.

This species of formalism, sometimes regarded skeptically in the word-rich art climate of the recent past, actually proclaims the visual power and abstract-thought possibilities of art in itself, rather than supposing that art must symbolize, illustrate or comment upon some other aspect of life. Puryear's approach, in the lineage of Brancusi and Noguchi, finds visual and physical qualities to be entirely sufficient, satisfying and significant in themselves.

Puryear focuses all his attention on form. Only one of the other 11 sculptures in the show has a form that approaches image (Plenty's Boast, 1994-95, red cedar and pine, which bears some similarity to a cornucopia). Instead, the rule is that Puryear's works evoke sequences of momentary or partial resemblances-one thinks of a shell, a venturi tube, a bell-but they never stop to take up a single identity. The passing associations furnish a convenient vocabulary and sometimes a title, but are never conclusive. The forms could be called irregular in the extreme-except that there is nothing truly extreme about them: the irregularity is exquisitely gentle, and the monumental scale breaks down into comfortable parts.

Often the contours of a work could be better known with the hands than with the eyes (if touching were permitted in a museum),

An untitled 1997 work of black-painted cedar and pine, for example, is shaped something like a plume. It sits sturdily on a flat- bottomed and approximately circular "stem," from which it rises with subtle swells, curves and depressions that also might recall a fleshy hip or the contours of a head. Then it leans its substance to one side, like a column of smoke cajoled by a lazy wind. The work does not look the same from any two viewpoints; it shifts in every detail and follows no formula of recession or any other sort of conclusion. It can be grasped only by circumambulation coupled with spatial memory, and even then characterization of it involves a string of conditions and disclaimers.

The work's satiny surface also escapes definition; the dark paint swallows grain and implies depth. The thought of a transitory shadow flits through one's consciousness.

In subduing image and evading simple summary, Puryear allows details to take on greater power. Process and workmanship are prominent. In virtually all his works, the viewer is led to study his methods. Construction, rather than other forming techniques such as casting or carving, is his means, undoubtedly because it allows process to be revealed to a greater degree.

Above, Alien Huddle, 1993-95, red cedar and pine, 53 by 64 by 53 inches. Private collection, New York. Photo Sarah Wells.

Right, Untitled, 1997, painted cedar and pine, 68 by 57 by 51 inches. Museum of Modern Art, New York Photo Sarah Wells.

Below, Thicke, 1990, basswood and cypress, 67 by 62 by 17 inches. Seattle Art Museum. Photo Michael Tropea.

Both the untitled black work and Alien Huddle (1993-95, red cedar and pine) are made of strips of wood, thin and flexible enough to be bent into a curve, and tapered so that they can join at one point or more on the unpredictable whole. Alien Huddle consists of three parts: a large sphere, a much smaller hemisphere and an even smaller quadrant of a sphere. The hemisphere clings to the side of the sphere with wood strips extending beyond its perimeter, creating the impression that it holds fast with arms. The smallest element nestles, protected, between sphere and hemisphere. Certainly a disparate but intimate threesome can suggest a family (and Puryear and his wife have one child).

But the complex indications of assembly seem equally important here. Because this work is not painted, its surface can be more easily studied than that of the black work. The wood strips are fitted together as neatly as the gallery's floorboards. They converge like lines of longitude that meet at the north pole on the sphere (and presumably on the bottom as well). The strips are pocked with straight-line indentations almost half an inch long. Chisel marks would angle into a surface, so one may guess-and a wall text elsewhere confirms-that these are the scars of staples that held the wood strips to an interior framework until glue dried, whereupon Puryear removed them.

This page and near left, Brunnhilde, 1998-2000, cedar and rattan, 93 1/2 by 112 3/4 by 73 1/2 inches.

Plenty's Boast, 1994-95, red cedar and pine, 68 by 83 by 118 inches. Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Mo. Photo Sarah Wells.

Here we see the trail of the maker in the work-the tally of his touches documented rather than concealed behind fine finishing. The marks are measures of time. Time, which in Puryear's works is never hasty, seems to be a gift that he offers to viewers; the ambiguous forms and constructive details of his sculptures counter the rush of everyday life. Except for the flat bottoms in contact with the floor, there are no straight profiles in this show. Straight lines always look fast and efficient, diagonal ones most of all. It's significant that they are largely absent here, and that they are found only in the latticelike constructions, where they suggest labor-- intensive methods rather than speed.

One such work is Thicket (1990), a basswood and cypress construction roughly 5 feet high and wide but only 1 1/2 feet deep. It is a puzzle of mostly rough-surfaced, massive pieces of lumber held by 11 pegs on each long side. Nothing is in a predictable relationship; the beams are not the same sizes, and although they pass through each other in fairly straight diagonals, the effect is entanglement, not movement. One of the most recent works in the show, Brunhilde (1998-- 2000, cedar and rattan), is visually much lighter and less imposing than Thicket, although more than 8 feet tall. Shaped like an inverted pocket open at the floor, it first appears to be made up of diagonally interwoven splines.

But a close look reveals that the strips of wood are in fact exactingly fitted together in a process of cutting, gluing and stapling. That Puryear did not use the obvious and easier methods of basketry (which he has employed in other works) implies that the labor must be part of the point.

Thicket and Brunhilde are also notable for their visual permeability. This is something th\at Puryear has come back to again and again over the years. He adopted basket and other vessel forms, and such structural enclosures as yurts, in earlier works, partly perhaps for their suggestions of shelter and service. But he also seems purely interested, as here, with opening the work to create a sense of place-an inside and outside that can be seen simultaneously. Visual permeability also reduces the mass of his works and makes them seem yielding and adaptable.

With another method and material that Puryear adopted about the time he represented the U.S. in the 1989 Sao Paulo Bienal-winning the grand prize and coming to international acclaim [see A.i.A., Jan. '90]-he found another approach to transparency. Confessional and Horsefly are both dated 1996-2000 and both made primarily of wire mesh and tar. Confessional is a 6 1/2-foot-- tall, 8-foot-long enclosure. The rippled mesh at one end almost seems to form an outline of the back of a human head (elegant neck, prominently curving skull). The other end brings to mind a door: it consists of two vertical wooden planks fitted together, stained, grooved with great circular sweeps as if of some huge saw blade, and interrupted with square, circular and elliptical holes and little blocky additions.

A low slab of wood on the floor could be an entry step or a kneeler. The enclosure is not a continuous sheet of wire grid but a patchwork of small squares of different mesh sizes and slightly different hues, from deeply black to rusty, sewn together (with wire) like a crazy quilt.

Horsefly is an assembly of rounded parts that includes a group of small panes of smoked glass on each side, a material Puryear is using for the first time. Undoubtedly these "compound eyes" gave rise to the title, but the form is no literal depiction. One looks at and through the nearly 8-foot-tall expanse, its different degrees of transparency offering a fractured view of the gallery it occupies and the works around it.

The surrounding works are, in fact, few: the exhibition sparsely occupied all the Virginia Museum's temporary exhibition spaces, with just two or three sculptures per room. In the gently curved galleries that can be problematic for painting shows, Puryear's organic contours were entirely at home. The show included a 1989 piece that was shown at Sao Paulo: Lever #2 is an elongated sequence of elegant wooden elements more akin to his works of the '80s than to the others in this show. An alcove outside the main galleries held three early wooden wall works from the '70s-a circle, a "barbell" and a "draped" line-that show the same tactile, abstract, vaguely allusive qualities as the recent works.

Also on view, although not part of the traveling exhibition, was a series of prints Puryear developed for a new edition of Cane, a book of poems and fiction published in 1923 by Jean Toomer, who was associated with the Harlem Renaissance. Fifty copies of the edition (Arion Press, San Francisco, 2000) are specially bound and enclosed in a wooden slipcase, accompanied by a suite of seven woodcuts, each titled with a woman's name. In Richmond, a set of prints lined the rotunda balcony. All are black-and-white abstractions with evocative elements such as wave lines, a sun-ray pattern, tendrils, and a parallel-line motif that could be a railroad track or a fence.

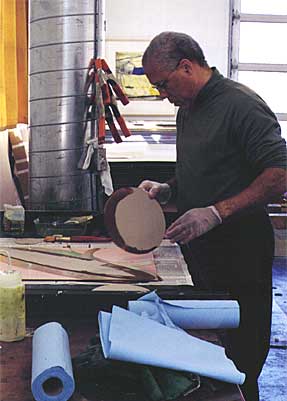

While these works may be specifically meaningful because of their source in Toomer's book, they also convey the sense of known aspects in an unknown whole that one sees again and again in Puryear's sculpture. Puryear started in art school as a painter and at one point studied printmaking, but his Peace Corps exposure to Africa and his study of furniture-making and boat-building led him down a path of real things and real purposes. The sweat of practicality shines through the abstract auras of his art.

"Martin Puryear," curated by Margo Crutchfield for the rima Museum of Fine Arts, debuted there [Mar. 6-May 27] and traveled to the Miami Art Museum [June 22-Aug. 26]. The show is currently on view at the University of California Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive [Sept. 12-Dec. 30] and will later appear at the Seattle Art Museum [Jan. 17-Apr. 21, 2002]. It is accompanied by a 70-page catalogue with an essay by Crutchfield.

Confessional, 1996-2000, wire mesh, tar and wood, 77 7/8 by 97 1/ 4 by 45 inches.

Horsefly, 1996-2000, wire mesh, tar, wood and glass, 97 by 95 3/4 by 79 inches. Edward R. Broida Trust.

Copyright Brant Publications, Incorporated Dec 2001