Cheryl Perkins' Tanzanian Experience in the Peace Corps

Training to be a PCV

Prior to becoming a Volunteer, I had three months of Swahili, cultural and teacher training with 24 other Peace Corps Trainees in Arusha. During this time we all lived with Tanzanian families in order to adapt quicker to the culture and lifestyle.

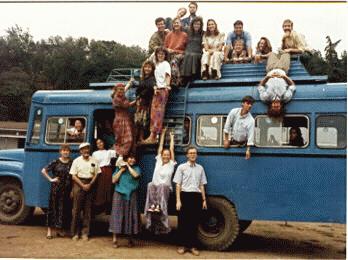

(22KB jpg) Peace Corps trainees and our "Blue Bus". I am sitting on the top of the bus in a light colored dress.

I lived in a little village called Kijenge in the outskirts of Arusha. Click for map As I walked the mile and half to and from the training site each day, I got many stares. Arusha is a pretty big tourist town, so the Tanzanians frequently see foreigners...but never in Kijenge village. I was anxious to learn Swahili so that I could explain to the curious why I was living in their village.

(19KB jpg) Village of Kijenge in Arusha, Mt Meru in background

It surprised me how fast I picked up the language. Each day we would have about five different language lessons. We were split up into six groups and rotated to different stations where a Swahili teacher resided. The teachers were top notch and made sure the lessons were fun as well as effective. Within one month I had learned more Swahili than I had learned Spanish in three years!

As I was improving in my Swahili, my relationship with my Host family also improved. There were two daughters, Grace and Frida, just about my age with whom I grew very close. There were also two young children in the family whom I simply adored (when they weren't being spoiled brats). My host family even put up with my vegetarian diet, although they couldn't understand it. There was only one occasion when the differences in our cultures really hit home.

(21KB jpg) Cooking with my host family

It was about four o'clock in the morning and I was awoken by a terrible screech. I looked out my bedroom window where Frida and Mama were removing the feathers from a headless chicken and Grace was positioning a live chicken for its termination. My heart dropped into my stomach as I ran back to my bed, hid under the covers and squeezed the pillow around my head to muffle any sounds. Aaaaaaaak! The pillow wasn't sufficient, I still heard the death screams. My sobs were approaching hysteria and I was sure I was going to hyperventilate. I knew that there were sixty chickens in all, so the nightmare wasn't even close to being over. I decided it would be best for me to go to the training site early to get away from the endless string of murders. I slowly composed myself, got dressed and opened the door. Just as I stepped outside the knife came down - aaaaaaaak! I screamed, "aaaahhhh!" My host family laughed. I couldn't believe it. They laughed at my misery. I sprinted from the house until I felt I was out of sound range of the dying chickens. It took me a full week to forgive my family for being so cold-hearted.

We were sworn in as Peace Corps Volunteers on February 18, 1994 at Ambassador Brady's residence in Dar es Salaam. We were all ready to go off on our own and to finally begin the work we had come to Tanzania to do.

Top of Page

Life on My Own

My Peace Corps work began in a little village called Peramiho in the southwestern part of Tanzania. Click for map The closest Peace Corps Volunteer was a day by bus away, so I knew I was on my own for a while until I made friends in the village.

My job in Peramiho was to teach Form III (equivalent to grade 11) Chemistry and Mathematics at Maposeni Secondary School. In turn for my services the school agreed to provide me with housing. Upon my arrival to Peramiho, however, the house had no roof. So I moved in with two teenage mothers and their babies. Good thing I had that Host family experience behind me.

My house had no electricity or water, so little tasks like washing the dishes required ample amounts of time. Rather than wearing myself thin with my domestic chores, I decided to provide work. I hired a recently graduated student named Gertruda as a house girl. While I was at school, Gertruda would fetch water, wash clothes and cook. That way when I returned home, I had time for my daily run and some relaxation.

A difficult aspect of living in Peramiho was that every where I went people stared at me. Most of the villagers had never seen a young, Caucasian woman before. Strangers would come up to me and touch my hair, children would chant, "Mzungu, Mzungu,..." (white person, white person), and friends would ask if my freckles were a skin disease or dirt. I wanted so badly for the people to understand that I was a person just like them - not some strange creature. I wanted to just blend into the crowd.

Gertruda became my close companion. I also acquired a cat to make my house seem more like a home. Amani (my cat) not only protected me from the monstrous cockroaches, he comforted me when I was feeling lonely.

(16KB jpg) My Tanzanian cat

Amani, Gertruda and I moved from house to house. The school could not afford to pay the rent of the first house so we moved into what I called 'the cave'. A dark, crumbling house with an indoor pit latrine. Amani had a wonderful time chasing after the cockroaches, rats, snakes and chickens which came in through the holes in the walls. Gertruda and I, on the other hand, dreamed of the day we would leave that house.

(20KB jpg) Gertuda and children playing cards on the porch of the 'cave'

I began to meet people by talking with others when I went to the market, attending the massive catholic church (although I'm not religious, and I couldn't understand the German priest's Swahili), and giving blood at the mission hospital (one of the best in Tanzania) each month.

I talked with the missionaries about my situation and they agreed that 'the cave' was not only inappropriate for health reasons, but lacked adequate security measures as well. They agreed to provide me boarding in a mission house, until Dr. Haule (name has been changed for privacy sake) was ready to move there in August.

So we went from cave to castle. The mission house was incredible. I had three bathrooms (equipped with running water), a sun roof, giant windows, electricity, painted walls, and a garage (for my mountain bike). I no longer was living like the typical Tanzanian, but I was too caught up in the luxury of European standards to care.

As the days progressed, I was growing further and further apart from the Tanzanian community. My house was part of the mission compound and thus was separate from the village. With running water and electricity, I no longer needed a house girl, so I let Gertruda go. After school I would visit with my next door neighbor, Dr. Banjas, and watch movies, cook, or play chess. It bothered me that I had become part of the ex-patriot community and not the Tanzanian.

Rather than moving into the house, Dr. Haule passed away in August. He had died of AIDS, after presumably contracting HIV from a prostitute when studying in Thailand. Before being diagnosed as HIV positive, he had passed the virus on to his wife. I went to a party one night which both Dr. Haule and his wife attended. The doctor sat off by himself drinking himself numb, while Mrs. Haule socialized and danced all night long. I was amazed how happy she seemed in spite of the horrible virus she carried in her blood stream. But towards the end of the party something went awry. Mrs. Haule was crying while hitting at her husband. The alcohol had kept her from holding her anger back any longer. For my first time, I saw a Tanzanian woman speak her mind to a male. I silently applauded her outburst.

Amani and I finally moved from the luxury house in November. We moved into what would become both my favorite yet most frightening house in Peramiho. By that time I had grown tired of living by myself, so I asked one of my students who lived far from school if she would move in with me. Elizabeth was thrilled and moved in immediately. We shared the chores of carrying water, cooking, shopping, cleaning, and hoeing, planting and weeding the garden. Elizabeth washed all the clothes, however, as she did a much better job than I did. I helped Elizabeth with her studies and Elizabeth helped me to improve my Swahili. I felt as though I had returned to being part of the village community.

(18KB jpg) Elizabeth and I enjoying our porch

Top of Page

The Adventures of Teaching

(11KB jpg) Maposeni Secondary School in Peramiho

I found teaching to be fun...but frustrating. It was difficult for me to remember the students' names because for one, they were names I had never heard of, and two, everyone had dark hair, skin and eyes! After about a month I finally had learned all of my students' names and faces. Another difficulty that did not go away was corporal punishment. When a student did anything wrong they were caned. On one occasion, when I first began teaching, I mentioned to a fellow teacher that some of my students were not doing their homework. He asked for a list of their names so that he could talk to them. Next thing I know, he calls the students into the teachers' room and caned all of them as I looked on with guilt. I never complained to a fellow teacher again about my students.

When the students found out that I disapproved of corporal punishment, many of them took it as an opportunity to misbehave. I decided that rather than punishing their bad behavior, I would reward their good behavior. The students didn't eat from the time they left their home for school at about 6:30 am, until they returned to their homes at about 3:30 pm. Thus, I rewarded students that did their homework with an andazi (similar to a doughnut) or popcorn. Unfortunately, once the novelty of the rewards wore off, students stopped doing their homework. In addition, some students felt as though they were being treated as an animal by being rewarded with food. Now this I didn't understand. Being beat with a cane (as all the animals are) is more respectful than receiving treats?

My next strategy was to keep any students that did not complete their homework after school until it was finished. I also explained to them that it was essential that they did their homework in order to prepare for the final exam. [Homework grades did not contribute to a student's final grade.] The after school punishment back-fired. Students saved their homework to do after school rather than doing it on their own. So I had very little time to myself...but at least the students were doing the work.

For each of my lessons I would come up with the most creative and memorable way to get the concept across. For example, when I was teaching about the difference in structures between graphite and diamond (two allotropes of carbon), I had the students become the carbon atoms. The students loved the lessons. But most never saw the relevance. It had been drummed into their heads that learning meant memorizing. No matter how often I told them otherwise, the students always opted to memorizing their notes rather than learning the concept.

Despite all the frustrations, I really enjoyed teaching. It was extremely difficult to get a concept across, but the times when I did made it all worth it. I would be explaining a topic, when all of a sudden my students' faces would light up. Then, the questions would come - expressing genuine interest. Once they understood something, they wanted to learn all about it.

In addition to their school work, students performed self-reliance activities such as; hoeing, weeding and planting the fields and gardens, carrying water and taking care of the livestock. In addition, every morning between 7 and 7:30 am, students had to clean the school grounds. There's no such thing as janitors - students always do the unskilled labor for the school.

There were many days when I would go to class and my students were not there. I 'd go stomping into the Head Master's office inquiring of the whereabouts of my students. He would usually inform me that my students were needed in the fields and would not be able to attend class that day. Wow, was that infuriating. You see, if the administration had planned it properly, all self-reliance activities would only be performed according to schedule. But due to poor planning, the students often had to re-hoe or replant, which doubled their work. I often suspected this was done on purpose to minimize the teaching load.

(17KB jpg) My students performing self-reliance activities while a teacher supervises

Top of Page

Robbed and Robbed and Robbed Again

After living in Peramiho for a year, I considered it my home. I had developed some very strong friendships with a fellow teacher and the nurse at my school. Elizabeth, the student who lived with me, referred to me as dada (older sister in Swahili), and I loved her as I would a little sister. I was known throughout Peramiho as Mwalimu Sherry (teacher Cheryl). At times I even forgot I was white. Unfortunately, many others could not.

I was the only white person in Peramiho that was not guarded behind the mission gates. I chose not to have a guard at my house for two reasons. First, most of my neighbors had more than I did. And second, I felt a guard would further emphasize the differences between me and the other villagers. It turns out that some of the villagers looked upon my choice to not have a guard as their opportunity to acquire my things. I was robbed three times in Peramiho.

The first time, somebody sneaked into the house during the night when Elizabeth had gone outside to use the latrine. Fortunately, the thief only had time to swipe my jack knife, radio, and running sneakers. I was furious that my sneakers were gone, however, because running was how I coped when I was upset.

About two weeks after the first robbery, a fellow Peace Corps Volunteer paid a visit. He, Elizabeth and I went to Dr. Banjas' house for dinner and a movie. I didn't like leaving my house unsupervised at night, but there was a bright full moon which I presumed would defer thieves. We returned home at about 10 pm to find the windows of the house broken. Someone had reached into the house with a stick and snagged what they could. A nineteen year old boy was found with my walk-man the next morning and brought to the police station for questioning. I pressed charges, hoping to get my other possessions back. Instead, the boy was sentenced to three years in prison and I was given a receipt for his jail term. I felt guilty about sending the juvenile to jail. It helped when I learned that this wasn't his first offense.

After the second robbery I made sure Elizabeth or I were always home at night. I also had one of the mission guards pass by my house every so often to assure all was well. In addition, I went dog searching. Most Tanzanians are deathly afraid of dogs, so I knew if I got a dog it would deter any more attempts to rob my house. I talked with the missionaries, and arranged to get a dog in a couple of months from an electrician who would be leaving Peramiho.

The dog didn't come soon enough. Elizabeth and I had guests one evening about a month after the second robbery. At about 10 pm, we escorted the guest home. After about five minutes I explained that I must return home in case someone is aware of our absence. I quickly walked home, causing Elizabeth and her friend, Sylvester, to fall behind. When I reached my house door and was putting the key in the lock, I heard Elizabeth scream. I turned around to find that I was surrounded by three men, as two others chased after Elizabeth and Sylvester.

The men seemed as though they had stepped out of a Rambo film, dressed in sleeveless T-shirts, jeans and a bandanna tied around each of their heads. Two of the men even had guns. It seemed unreal. Throughout being tied up, punched, kicked and watching as the thieves went through the house taking whatever they fancied, it all seemed like a dream. Reality hit when one of the men informed me that Elizabeth had been killed. I was frozen with fear.

The worst part about the ordeal wasn't what they stole or what they did. The worst part was not knowing what happened to Elizabeth and Sylvester until three hours after the thieves had left my house. I loved Elizabeth, and I was trying to help her. I was responsible for her welfare, and by living with me her security was being compromised. It turned out that both Elizabeth and Sylvester were fine. They had gone to the police (5 km away) for help. They had tried the neighbors, but upon learning the thieves had guns the neighbors were too afraid to help.

The police gathered all possible suspects, about 50 men and boys in all, for a line-up the next day. There's no one-way glass in Tanzania, so Elizabeth, Sylvester and I had to look face to face at the suspects for identification. Elizabeth and Sylvester each picked out one guy from the line-up. I, on the other hand, was too intimidated by the cold, dark eyes staring back at me to pick anyone out as a criminal. The police tried to get me to identify the man Elizabeth and Sylvester chose as one of the thieves (who happened to be the assistant police officer who had claimed to be helping me with the previous robbery). But I just didn't feel certain enough to make that commitment.

Despite the string of robberies I experienced in Peramiho, I did not want to leave. I felt I should set an example for my students that no matter how difficult things may get, don't give up and run away. Unfortunately, Peace Corps wouldn't give me that opportunity. It was decided that Peramiho was too dangerous, and the school didn't show enough responsibility for me to remain there. I had to leave my home. I will never forget the farewell song my students sang for my departure...

Life is short.

It comes and passes.

Like rain water

leaving mud behind.

Cheryl our sister,

we say good bye. (Translated from Swahili)

Top of Page

My Days in the "Big City"

Although I had to leave Peramiho, I requested to remain in Tanzania. I didn't want to leave the country on a bad note. I knew that most Tanzanians were very caring and good, and that a few corrupt souls shouldn't destroy my perception of the rest of their population. In addition, I wanted to monitor the construction of the hand-pump well in Peramiho for which I had been granted funding.

(36KB jpg)

The Director agreed to have me stay on as a volunteer, assisting the Peace Corps staff in the Dar es Salaam office. I would design the Resource Library, provide volunteer support, facilitate training sessions and periodically visit Peramiho to monitor the construction of the hand-pump well. More than enough work to keep me busy and feeling useful.

I also had the task of finding an affordable place to live. For the first month of living in Dar es Salaam, I stayed in a guest house for Tanzanian monks. The monk in charge of the guest house, Brother Kizito, coincidentally had attended St. Anselm college with me in Manchester, New Hampshire. I can see why the religious life is attractive to Tanzanians. The monks had a much higher standard of living than the typical Tanzanian. Just the same, the Brothers were the kindest men I had come across in Tanzania.

Next, I got the opportunity to house sit for an embassy worker. Since Tanzania is considered a hardship country, any U.S. government worker placed there is provided with luxurious housing. I never thought as a Peace Corps Volunteer I'd live more extravagantly than I had in the U.S. Of course, by that time I considered a television and microwave to be precious devices.

For my final 5 months in the 'Big City', I lived with Robbie Nelson. Robbie had served as a Peace Corps Volunteer and then took on a position in Population Services International as a social marketer for Salama Condoms. PSI is doing an excellent job at spreading HIV awareness throughout Tanzania. Condom, once a taboo subject, is talked about freely, as the crucial alternative to abstinence for preventing the spread of HIV. As you can tell, I was very proud of the work Robbie was doing.

I had great fun living in Dar es Salaam, thanks to Robbie. From bar hopping to snorkeling to visiting with friends, my life style in Dar was anything but dull. It was strange living in the city, where all the white people have lots of money. I felt I didn't fit in with the ex-patriots and embassy workers, yet I wasn't getting the typical volunteer experience either. The loneliness I had felt in Peramiho was resurfacing, but this time it was a consequence of my isolation from the white population. My solution? The same thing as I do in the U.S.. I keep very active and try to always enjoy myself.