RPCV William Niles returns to Niger

AFRICAN ISLAMISM, FROM BELOW

Dec 1, 2003

World & I, The

William Miles

Not even my village friends thought I would still come. Only six weeks after the September 11 attacks on the "marketing hub of the Earth," and a few days into the bombing campaign against Afghanistan, my black African Muslim hosts assumed I would postpone my trip back to the Islamic heartland of Nigeria and Niger. They guessed that I had heard that anti-American riots in the nearby city of Kano had taken the lives, in retaliation, of hundreds of indigenous Christians. They knew how perilous air travel for Americans had suddenly become. No, went the conventional wisdom, Mallam ("Teacher") Bill would not arrive as scheduled.

It might not be prudent.

Thus did I return in October 2001 to a city plastered with bin Laden wall posters and bumper stickers. Never had Kano-an ancient, clay -baked, sub-Saharan city, once a jumping-off point for trans- Saharan camel caravans-felt so hos tile. Never had I been so anxious to leave the bustling, rather frenetic, capital of Hausaland for the relatively placid countryside. It was a Friday afternoon, and the hisbah-selfappointed Islamic militia-were already setting up roadblocks throughout the city, stopping traffic, and inducing the lukewarm faithful to pray, or at least to cease from driving.

This is the religiously muscled Nigeria that friends of Africa dread reading about these days-the Nigeria of anti-Miss World riots and fatwas, of death by stoning sentences for "adulteresses," of limb amputation for petty thieves. What would be my reception, now that my government had declared war on the man whose face was plastered everywhere in the city-not as in "wanted" posters, but rather in heroic poses?

More important, what has been happening to Islam in West Africa?

Since serving as a Peace Corps volunteer in Niger in the late 1970s, I have been returning to the same two Hausa villages on either side of the Nigeria-Niger boundary. Niger is ranked by the United Nations as the second-least-developed country in the world. (Sierra Leone captures the dubious distinction of placing dead last on the UN's Human Development Index.) Nigeria, thanks mostly to its prodigious petroleum reserve (it is America's fifth-largest supplier of oil), fares better, at least on paper. But in the remote bush, on the harsh, semi-desert landscape of the Sahel, one needs a keen eye to discern the advantage of living in Nigeria, Africa's most populous nation.

Neither village, despite hefty populations of well over six thousand, enjoys running water or electricity. Health care is rudimentary: infants die of diarrhea, the blind still beg, and the crippled and leprous depend on the intertwined will of Allah and community sadaka (charity). Yet this is precisely what is so humbling to a Westerner: the generosity provided by impoverished communities to the most unfortunate among them. For all the horror stories we may hear about African countries, African villages have much to teach us about solidarity. It is perhaps in the African village that we can still find the redemptive face of Islam.

But for how long?

LIVE AND LET LIVE

I slam first came to what is now Nigeria and Niger in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The Wangawara, itinerant Muslim traders from the Sakel, combined missionary zeal with commerical prowess as they traveled among and traded with the Hausa people, who until then had practiced animism and polytheism. The expansion of Islam was slow, however, and confined mainly to royalty, the merchant elite, and urban dwellers. For hundreds of years, Islam cohabited with traditional African beliefs.

In the same period that the thirteen American colonies were consolidating their newly attained independence into a single polity, West Africa was experiencing its own integrative revolution. Its rebellion was over religion bereft of authenticity, not taxation without representation. Disgusted by the "corrupt" manner in which the faith was being practiced by greedy tyrants, Islamic reformists waged jihad against nominally Muslim but overly heterodox potentates. In the area that became northern Nigeria and Niger, the jihad was led by a sheikh of the nomadic Fulani tribe, Usman dan Fodio. In the first decade of the nineteenth century, dan Fodio established a veritable Islamic empire over what had been a loosely amalgamated set of Hausa kingdoms and fiefdoms.

Although the Fulani conquerors attempted to maintain their exclusive royal identity and prerogatives, they soon began to assimilate into the ethnic majority, incorporating Hausa language, culture, and women. Eventually, the rulers of northern Nigeria would be known generically as Hausa-Fulani.

But Fulani domination was undermined more spectacularly from without than within. One century after dan Fodio conquered the Hausa in the name of Islam, Lord Frederick Lugard conquered the Fulani in the name of Pax Britannica. British colonialism, however, did not reject establishment Islam. To the contrary, Lugard's policy of indirect rule exploited existent institutions-including the HausaFulani emirates and Islamic jurisprudence (sharia) -to facilitate its hold over northern Nigeria. Indeed, under British colonialism Muslim conversion campaigns Islamized both pagan redoubts in the hardcore north and many minority groups in the middle zone.

(In nearby Niger, the French-still infused with anticlerical sentiments from their revolution-practiced direct rule and cast a more suspicious eye over the Islamic rulers and institutions under their domain.)

Not all of Nigeria was Muslim. Only about half was, with the southern regionspopulated mainly by Ibo and Yoruba-proving more fertile ground for Christianity. This became particularly evident after Nigeria gained its independence in 1960. Still, despite the religious undertones to the Biafran civil war (a Muslim-dominated federal government suppressing a secession by Ibos), religion itself in Nigeria remained basically a domestic, "live and let live" affair. Until the 1980s, that is, when Iranian Shiite, Saudi Wahhabite, and homegrown influences began to plow a fundamentalist path. That is also, by chance, the time of my personal initiation into village life among the Hausa along the Niger-Nigeria borderlands.

In the two decades that have followed, I have witnessed several subtle transformations, including that from bare breasts to hijabs.

SLOW ISLAMIC REVOLUTION

For a bachelor in his twenties, whose earliest adolescent exposure to "girlie" pictures had come more from National Geographic than Playboy, living in a community where women performing household tasks nonchalantly revealed their bosoms was more than intellectually stimulating. Yet there was absolutely nothing suggestive or seductive about the gesture; it was a natural part of the rural African lifestyle. In the early morning, even before donning my glasses, I would often emerge from my hut and, in a myopic haze, recognize my next-door female neighbors not by their faces but sheerly by the size and shape of their breasts.

Only then could I proceed to greet them. On the other hand, never did I glimpse so much as the calf or-Allah forbid-knee of a postpubescent female villager. That would have been haram, Islamically forbidden.

Such paradoxical decorum typifies the longstanding, successful cohabitation of African norms with the Islamic religion in large swaths of the sub-Sahara. Sociologists call this phenomenon syncretism. Politicians prefer to speak of coexistence and tolerance. Whatever the word, the phenomenon is part and parcel of an African liberalism that, in even the most remote and thoroughly Muslim communities, preaches peace for all and extends hospitality and friendship to nonnative and nonMuslim strangers.

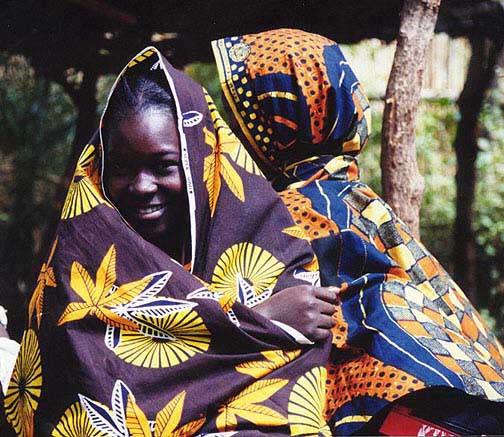

However, even in Africa, fundamentalists perceive accommodation as backsliding. In the villages to which I have been returning these past twenty years, it is now more common to see women-and even young girls-wrapped up in nunlike habits than insouciantly laboring topless under the burning Sahelian sun.

This is not the Taliban. The Islamic schools that have recently sprung up on both sides of the border (full day in Niger, after school in Nigeria) enroll young girls as well as boys. Females need only be dressed modestly. Better to habituate them to the hijab early in life, goes the thinking, than to impose the restrictive garb when they are older. Surprisingly, rather than viewing madrasahs as competition, the principal of one of the regular government schools had this reaction: "As long as the children go to school, it doesn't matter which one." School choice comes to Muslim Africa.

I visited one of these "Franco-Arab" madrasahs in a village in Niger, a one-room school in which children clustered on the floor based on their age-groups. Their textbooks were published in Saudi Arabia, which had also financed the building of the school. Upon little black tablets the barefoot pupils etched out their Arabic ABCs in chalk. The Qur'anic schoolmaster welcomed me warmly, pleased that I had decided to visit and more than happy to accommodate my wish to photograph his school and wards. he did harbor one worry, however, which he expressed, plaintively and mournfully, as a question.

"In your country," he asked in Hausa, "do people distinguish between Muslims and terrorists?"

"Our leaders do," I responded frankly, "but there are ordinary people ..." ("people of the street," he broke in, clarifyi\ng my idiom) "who do not."

The Islamic schoolteacher remained sad. "Islamiyya," he concluded softly, "addini zaman lafiya. Islam is a religion of peace."

Yet even on the village level, the popular saying "There is no compulsion in Islam" appears undermined by the loud-speakers that, beginning before dawn, loudly and emphatically call the faithful to prayer.

It is Friday afternoon, around two o'clock. Prayer time. I emerge from my hut to distribute sabbath alms to a passing person in need. Instead, I walk smack dab into a huge assemblage of men readying to prostrate themselves in the most communal event of the week. One of them calls out to me, gesturing for me to join the crowd in prayer.

Since I was the only non-Muslim in the village, my discreet response would be to decline politely and return to my hut. At this moment of global tension between Muslims and "infidels," might not a single dissident, crank, or vigilante passing through the community question the "contaminating" presence of a white and-since I have never hidden it-Jewish stranger?

Instead, I feel compelled to squeeze between two prayer mats and mimic as best I can the gestures of these faithful. When they rise, I rise. When they bow, I perform a half-bow; when they kneel, I crouch. When they spread their hands and look to their palms, I faintly open mine. When it is over, I join my surrounding prayer mates in solemn hand shaking.

Afterward, an elderly, educated (a former school principal) courtier of the district chief approached me.

"I was surprised to see you there," he said in French.

"I wanted to be with you," I replied.

"And yet," he went on, "I noticed that you didn't open your mouth."

I was at a loss.

"One must learn," he encouraged me, in what was to be the only hint of proselytizing I would encounter during my entire visit.

THE DE-AFRICANIZATION OF NORTHERN NIGERIA

Double-gongs of a silver-tin alloy, long trumpets of silver or beaten brass, wooden horns, or reed instruments which sound like bagpipes figure prominently in the praisesinging addressed to rulers and senior titleholders .... Thus did the eminent Jamaican-born anthropologist of the Hausa, M.G. Smith, characterize the musical accompaniment of the maroka, the praise singers who roam the land to laud the virtues of (hopefully) munificent patrons. In the countryside, the instruments might not be so elaborate, but even simple clay and goatskin drums can add rhythmic excitement to any festive African occasion.

Might not the return visit of a fully tenured professor-the equivalent, I reasoned, of Smith's "senior title-holder"also justify the commissioning of a praise singer and backup band?

So it was that I wrote to Lawal Nuhu, my faithful correspondent in the Nigerian village along the border, to prepare the gig. My motive was not entirely egomaniacal: with the onset of middle-age memory loss, I wanted to commission a ballad to reconstruct those details about my previous life in Hausaland that I could no longer recollect. I was also curious about perceptions about me by my hosts in fieldwork-what is known more eruditely as ethnographyto which I had always been oblivious.

Lawal's response came as a shocker. On account of the extension of sharia to Katsina state, in which the village lies, "singing, beating of drum, blowing flute and all sort of evil vices have been banned [and] are strictly forbidden." In short, much of traditional Hausa folkways-including public dancing, wrestling, and praise singing-had recently been criminalized.

An impressively turbanned alkali (Islamic district court judge) now rides circuit from the emirate capital once a week, on market day. A scribe accompanies the alkali. So does a policeman, whose ostentatious display of handcuffs on a table in the makeshift courtroom is sufficient reminder that sharia is indeed the law of the land.

It is understandable that the West pays particular attention to legal statutes that impose capital punishment for extramarital sex and amputation of limbs for petty thievery. Such punishments do offend an emerging universal standard of human rights. Less recognized is the extent to which sharia, as applied in northern Nigeria, represents cultural de-Africanization. Remarkably, it is a virtually voluntary deAfricanization. Upholders of the traditionhere on the borderlands of Nigeria, the very emir-proudly announce the prohibitions to the people.

The former French colony of Niger, on the other hand, has staunchly maintained a relatively clear-cut separation of mosque and state. Sharia may be used for civil matters, but there is no nationwide religio-judicial system comparable to what is evolving in northern Nigeria. As a result, some border towns and villages in Niger have become havens for newly criminalized activities in Nigeria-especially drinking, gambling, and prostitution. To that unholy trinity of vices I have personally added an additional sin. So as to circumvent the newly imposed strictures of sharia in Nigeria, I hired my praise singer, musicians, and girl singers from a Fulani (seminomadic shepherd) village just over the border, in Niger Republic.

Twenty years ago, I noted differences in observance of Islamic principles and rituals across the border. My favorite example was the part of the wedding ceremony when the bride is escorted to the groom's home. What I witnessed in Niger bore out Spencer Trimingham's observation that in this marital "rite of passage. . .the indigenous element remainfs] dominant and the Islamic aspect negligible." The teenage girl was wrapped in elaborate, colorful cloths, a high-brim hat was put on her head, and a large pair of sunglasses covered her eyes. She was then put on a horse with a younger sister sitting just behind, on the rump.

Drummers followed the girls as the horse was led to the groom's house. Along the way, there was much singing and dancing.

In Nigeria, however, this custom had already been declared un- Islamic by the religious establishment. As a result, in villages just across the border it was no longer practiced. Instead, the bride was driven in a minivan, horn honking liberally. Today, however, the bridal horseback procession is no longer practiced on the Niger side of the boundary, either. Nigerian norms of Islam are spilling across the border and, even in the remote countryside, de- Hausifying tradition.

Yet it is nt only Nigeria that is affecting Islam in Niger. As a result of the hajj (pilgrimage), significant numbers of Nigeriens, rural as well as urban, spend months and years in Saudi Arabia. Long- term Hausa residents of Saudi Arabia are motivated more by economic reasons than sheer piety, but along the way they do acquire and assimilate Saudi, and therefore Wahhabist, interpretations of Islam. Not only has travel to Mecca from rural Hausaland increased over the past fifteen years, so has the incidence of purdah- secluding one's wife or (in this very polygamous society) wives.

BLACK BEANS AND BIN LADEN

It was in this context of intensified Islam that the stunning news of September 11 hit Hausaland. Niger was the first African country to publicly support the U.S. campaign against the Taliban in Afghanistan. President Mamadou Tandja took decisive action when leaders of two Islamic organizations (including the Nigerien Islamic Organization) addressed a letter accusing the Bush administration of infringing upon human rights and democracy and threatened retaliation. These organizations were banned and the letter writers suspended from their posts. In my village, "If anyone here went around yelling 'bin Ladin only!' " I was told, "the chief would call him to order.

If he continued, the chief would have him arrested by the gendarme."

Nigeria, too, officially supported the United States in its post- September 11 military action. Yet in Kano city, bin Laden posters and bumper stickers were already plastered all around by the third week of October. A market clash degenerated into a lethal anti- Christian, anti-American riot, leaving two hundred dead. On the face of it, it would appear that pro-bin Laden sentiment in Nigerian Hausaland was high.

That was not, however, my experience in the countryside. There, the attack on the "market center of the world" (the Twin Towers) was also perceived as an assault on major Hausa cultural values: not only innocent life but trade and commerce. Also popular, however, was an ambiguous assimilation of September 11 into Hausa historiography: a newly created folktale called kunain baken wake (burning black beans).

There once was a tyrannical ruler who forced his subjects to carry him long distances. he rode them like horses, abusively. A man named Daga, hearing what was happening, declared, "Next time the prince is looking for a porter, put the saddle on me. There won't be any more 'person riding" after I do it." So Daga found himself carrying the prince. Near the I path the prince noticed a group of people, and a fire blazing. The prince ordered Daga to bring him closer, so that he could see. So Daga went 'trotting' forth-right into the fire, burning himself-and the j wicked prince-to death. Daa- he was the first "black bean burner."

A classical Hausa dictionary renders the expression "burning black beans" to mean "reckless courage." Village informants described it more as a demonstration of manliness. While the killing of innocents is condemned as terrorism and un-Islamic, the parable of the "burnt black beans" docs not condemn Daga's suicidal action against injustice and tyranny. Post-September 11, the struggle over the black African Muslim soul boils down to the facile acceptance, or principled repudiation, of Osama bin Laden as a modern-day Daga.

Disgusted by the "corrupt" manner in which the faith was being practiced by greedy tyrants, Islamic reformists waged jihad against nominally Muslim but overly heterodox potentates.

In the villages to which I have been returning these past twenty years, it is n\ow more common to see women-and even young girls- wrapped up in nunlike habits than insouciantly laboring topless under the burning Sahelian sun.

A scribe accompanies the alkali. So does a policeman, whose ostentatious display of handcuffs on a table in the makeshift courtroom is sufficient reminder that sharia is indeed the law of the land.

Nigeria, too, officially supported the United States in its post- September 11 military action. Yet in Kano city, bin Laden posters and bumper stickers were already plastered all around by the third week of October.

William Miles is professor of political science at Northeastern University in Boston. he was last in Hausaland thanks to the American Philosophical Society.

Copyright Washington Times Corporation Dec 2003