Homesteading in Malawi, the Warm Heart of Africa by Peace Corps Volunteer Laina Poon

Homesteading in Malawi, the Warm Heart of Africa

LAINA POON

MALAWI, AFRICA

I pushed the pile of ivory maize kernels off my lap, luxuriating in their coolness and smoothness as they slid through my fingers. The sun is just beginning to spear through the bare branches of the Baobob tree behind my hut, promising another clear, hot day. Stretching the stiffness out of my back and examining my hands for blisters, I marvel at my Malawian companion's ability to sit on a reed mat with a sleeping baby strapped to her back and shell her way through a mountain of maize without a single blister or word of complaint.

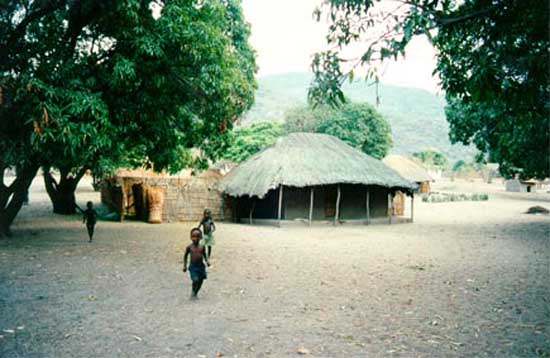

As a Peace Corps Volunteer in Malawi, a small country in south-eastern Africa, I lack the leathery hands and work-toned body of my fellow villagers, but I put in my share of labor as well as I am able. My official job is to work with the Malawi Department of Forestry helping rural communities to find ways to better manage their natural resources. This is not an easy task, as it requires learning local languages and culture, and living as a villager among villagers. In order to work successfully in Malawi, one must work Malawian-style, not American-style, and it takes time to understand the culture well enough to do that.

I count myself blessed to have the opportunity to learn the subsistence lifestyle of my African peers. Never before have I known the satisfaction of living almost entirely off my own power. I farm a small field and kitchen garden so that I can eat food which has never been touched by chemicals or confined by packaging, cook on a mud stove, and go places on a bicycle propelled by my own breath and muscle. I am lucky to live in a hut with a tin roof instead of a grass roof, and luckier still to have someone to help me with chores. My helper draws water from the well and carries it to my house, washes my clothes in the river, and scrubs my pots and pans with sand to remove the soot and grime. There's no electricity within 18 miles, and the nearest paved road is 40 miles away over eroded dirt tracks and sand-trap "roads" but that ceased to bother me long ago. I've lived here in the bush for almost two years, reading by candle light under my mosquito net at night, and bathing by cup and bucket under the Milky Way and the Southern Cross.

Solar fruit and vegetable dryers

My latest project is helping villagers construct solar dryers out of locally available materials. Food security and nutrition are problems here in Malawi, so if people were able to store fruits and vegetables in dried form, they would not be so dependent on the seasonally determined selection of foods (which, at times, is quite lacking).

To make a simple solar dryer, start by obtaining a split bamboo basket (the ones we use in the village are about 2-1/2' long, 1-1/2' wide, and 1-1/2' deep) or other medium-sized wooden box. Cut ventilation holes towards the bottom edge of one side of the box, and towards the top edge of the opposite side to allow heated air to escape and cooler air to enter from below. This removes moisture from the fruits or vegetables placed on a rack suspended inside the box. Screen your ventilation holes with mosquito netting to prevent flies from entering.

Next, poke two sets of holes across from each other to hold the sticks that will support the removable interior drying rack. Cut four more straight sticks to size and lash them together with twine or the inner bark of the Mombo tree to make a rectangular frame. Carefully bind stretched mosquito netting over the frame you have just built to construct a mesh rack upon which you will lay the items you want to dry. Or, if you are lucky enough to have old galvanized steel window screens lying around, use one of those for your drying rack.

Cut and sew a black plastic liner for your box so that it fits neatly inside, and secure it around your ventilation holes and two interior struts. Now the inside of the box is a black hole that will soak up energy from the sun to dry your produce. Instead of using plastic, you can simply paint the interior black, using only paint which will not fumigate your fruits and vegetables with noxious chemicals. Black paint in the village is made from powdered charcoal and turpentine, which, when heated, gives off gasses undesirable to combine with food.

Finally, cut a piece of clear plastic a bit larger than the top of the box to serve as a lid. The plastic can be tightly fixed to the box by means of a thin strip of old tire, or a bungie cord if you have one. Slice your fruits or vegetables and soak them in a solution of half lemon juice, half water, for five to ten minutes depending on the size of the pieces. This reduces unsightly browning. Place the slices on your mesh rack so they are not touching each other. You can dry anything that doesn't have too high a moisture content, like pumpkins, sweet potatoes, onions, leafy vegetables, herbs, tomatoes, and almost all fruits. If the remaining moisture content is too high after you have dried the foods, they will mold when stored. If you have dried them thoroughly, however, they will keep for years when stored in an airtight plastic bag.

Malawian cooking

It is almost noon now, and I can see the Muslim members of our community walking to the mosque, their flowing white nkanjo (outergarment worn for prayer) brilliant in the African sun. Time to start preparing lunch. I grab a basket and head toward my garden, passing dusty children kicking a ball made from tightly wadded plastic bags bound with rubberized twine. My favorite accompaniment to rice or nsima (soft patties made from maize flour) is pumpkin leaves, or mkhwani.

Pushing aside the dry maize leaves in my garden, I pick my way over the ridges, pausing to pluck palm-sized or smaller pumpkin leaves from the vines winding between the maize stalks. We intercrop maize with pumpkins and beans in Malawi, the former to shade the soil and slow evaporation, the latter to fix nitrogen, adding fertility to the soil and nutrition to our diet. Basket full, I meander back through the village to my hut, sit down on the porch with my neighbor, and start processing the leaves.

When I first came to Malawi, I was frustrated by my inability to de-string pumpkin leaves, much to the amusement of the local women. Now, however, it's second nature. Holding the leaf upside down by its stem, you see that the stem is hollow. Use your thumbnail to split half or a third of the stem and snap it backward so that the flesh breaks cleanly, but the outer fibers do not. Pull gently downward, removing the fibers from the outside of the stem and the back of the leaf. Repeat until you have de-strung a good pile, because, like all greens, pumpkin leaves cook down quite a bit.

Mkhwani

3-4 cups de-strung and chopped pumpkin leaves

3 medium tomatoes, chopped

1 tablespoon oil

Water

Salt to taste

Heat oil, a little water, and salt in a pot. Add tomatoes, then pumpkin leaves. Cover and simmer over medium heat 5 minutes or until greens are tender. Serve over rice or, in Malawi, with nsima. A favorite breakfast dish of mine is futali, or boiled sweet potatoes with peanut flour. It's easy to make, and will keep you strong working the fields for hours. In the village, we make peanut flour by shelling raw, dry peanuts (or groundnuts, as they are called here) and pounding them in a huge mortar. After pounding a little while, we scrape the crushed nut bits out of the bottom of the mortar and bounce them in a flat winnowing basket to separate the fine flour from the coarse granules. Coarse bits are put back in the mortar for more pounding until a medium-fine flour is attained. Winnowing is a difficult skill to master; I still can't manage to separate big bits from small or heavy bits from light with any efficiency. The fine peanut flour is set aside and the bits and chunks put back in for more pounding until you have the right quantity and consistency of flour.

Futali

3 - 4 cups peeled and chopped sweet potato

1-1/2 cups peanut flour

Water

Salt and sugar to taste

Prepare sweet potatoes by peeling and cutting into bite-sized pieces. Boil in salted water just until tender. Drain out some of the water remaining in the pot, leaving about three-quarters of a cup. Different types of sweet potatoes absorb different amounts of water, so you'll have to do a little experimenting with how much you put in. Add peanut flour and return to a boil, then simmer about 10 minutes. Serve with sugar and a dash of cinnamon or nutmeg if you wish.

. . .

I hope you've enjoyed a little glimpse into my life here in Malawi. I can't express how glad I am to have undertaken this journey of personal growth through learning and teaching in a very different culture than my own. Not only do I now have perspective on the type of subsistence farming life many of the world's people live, I have learned perseverance, flexibility, patience, and how to find happiness in a life of simplicity.

Because of my experiences in Malawi and inspiration from my farming grandparents and COUNTRYSIDE, I am planning to continue homesteading when I return to America. This article is my enthusiastic response to receiving my first two issues of COUNTRYSIDE magazine, a gift subscription from my grandfather.

Part of the homesteader philosophy in which I believe strongly is community cohesion-we all benefit when we support each other, be it sharing extra garden produce, or coming together to help raise a barn. You can think of community as the people in your neighborhood, your county, or, as I learned in Peace Corps, as the people of our world. Extend your homesteading spirit beyond the people you know to the people you don't: volunteer, and make the world a better place.