Honduras RPCV Mike Bell gets jobs for Mexicans

N.C. recruiter gets jobs for Mexicans

Company says it offers immigrants a chance; critics say it's exploitative

By MOLLY HENNESSY-FISKE, Correspondent

SANTIAGO IXCUINTLA, Mexico -- As the recruiter sped past the sun-baked fields between Guadalajara and the Pacific, the workers were waiting.

They whispered as the gringo's silver pickup flashed by like a charm in the sun, then called out from street corners: "When's the meeting?"

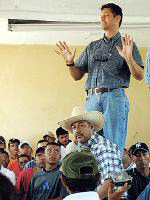

By the next morning, word had trickled down the dirt roads of this town of 18,000, into houses without running water where parents and children share beds. Hundreds came to meet the gringo in the white ostrich-skin boots, pressing so close in the heat that a woman fainted.

Mike Bell, a native of Mebane, N.C., matches Mexicans hungry for work with U.S. employers hungry for low-cost workers. His company, Manpower of the Americas, last year supplied U.S. employers with 15,000 Mexican guest workers, more than half of whom went to North Carolina.

Many Mexicans covet the chance to work legally in the United States, but work visas are difficult to get. With the U.S. government's blessing, Bell and other recruiters control who has access to the legal pipeline, and at what price.

Even without legal permission, millions of immigrants travel to the United States for work. Federal authorities say as many as 10 million illegal immigrants are in the country.

President Bush has proposed a visa program for those illegally employed and others who hope to work in the United States. They would be allowed to stay for up to six years. Proposed legislation indicated similar ideas for turning illegal immigrants into legal guest workers.

All the reforms build upon the established guest worker system. About 188,000 foreign guest workers took temporary jobs in the United States last year. About 78,000 came from Mexico.

Seasonal workers began crossing the border from Mexico 60 years ago to fill low-wage jobs, such as picking meat from crabs, mowing golf courses and clearing farmers' fields.

Farmers in North Carolina employ more Mexican guest workers than in any other state. More than 14,000 guest workers took jobs in the state last year, most of them farm workers from Mexico.

Proposed programs would not affect the central role recruiters play in the system, one critics say exploits the desperate through gouging and blacklisting.

"The government is already involved in the process. They should be monitoring the treatment of these workers," said Bruce Goldstein, co-executive director of the Washington-based Farmworker Justice Fund. "We claim this is a benefit to the workers and the countries that they come from. We should make sure that the benefits are real."

Processing workers

Bell started his recruiting business four years ago, working out of the busy bus terminal in Monterrey, 145 miles south of the Texas border. Now Manpower of the Americas has an office and a staff of seven to coordinate workers' visa applications, interviews at U.S. consulates and passage to the border, where the workers catch buses to their new jobs. Bell's company is not related to Manpower Inc., a large staffing-services company, although its mission is the same -- filling temporary jobs.

Candidates apply for two types of visas: H2A for farm workers, H2B for other temporary laborers.

Bell, who deals with both types, calls himself a processor. "Recruiter" and its Spanish equivalent, "contractista," sound too negative, he said. Some people unfairly label him a "slave driver," he said, while others accuse him of importing cheap labor at the expense of Americans' jobs.

"When you're trying to do everything right," he said, "it makes you feel really bad."

Bell, 42, picked tobacco during his high school days in Mebane. After graduating from UNC-Wilmington, he served as a Peace Corps volunteer in Honduras and later worked for the N.C. Employment Security Commission.

He decided to put his Spanish to use working with migrants. He became a teacher for migrant children in rural Johnston County, a migrant health advocate in Siler City, N.C., and migrant health/safety advocate with the N.C. Growers Association, a group of about 1,000 farmers using guest workers.

He talks about the growers association with a convert's fervor. He once heard horrible things about it, he said -- that bosses abused workers, put them in run-down housing and paid meager wages. But he saw workers living better than they would in Mexico, making better than minimum wage; the pay this season is $8.06 an hour.

"If you want to make sure people are watched and helping them, this is it," Bell said, blue eyes shining. "I saw the light from the field."

Before his recent meeting in Santiago Ixcuintla, Bell visited an N.C. Growers Association guest worker nearby. Hipolito Ornelas Villegas, 36, showed off the house he built with $3,000 he earned picking tobacco last year in Clinton, N.C. This season, he plans to replace the cooking fire outside with an electric stove.

Ornelas told Bell in Spanish that he knows at least 40 others in the neighborhood who would like to work in the United States. "There are a lot who cannot go because they do not have the money."

The upfront costs are considerable. Applicants pay Bell's agents $40 and his company $105. They pay the U.S. consulate $100 for an interview and $100 for a visa. Counting bus tickets, hotel rooms and food, many pay $600 to $800, much of it borrowed from family and friends.

Bell expects to process 13,000 applicants this season, which means more than $1.3 million for his company. He complains of high overhead but would not disclose his earnings. He said he gets no fees from U.S. employers.

"I charge money, but so do polleros," he said, using a Spanish term for smugglers. "Nobody goes across the border free."

Consular guidelines recommend workers pay no more than $600 for expenses, transportation, consular and recruiter fees. But Thomas Canahuate, H2 program director at the U.S. Consulate in Monterrey until this month, said the rules aren't binding.

Canahuate, now vice consul, said he has heard of recruiters charging workers as much as $2,000. "It gets to the point where these people are basically buying the visa," Canahuate said.

Canahuate said his concern is not just that workers are being gouged. If they borrow a lot, they are likely to stay in the United States illegally to pay off the debt.

The consulate in Monterrey issued 66,379 visas last year. And more of those workers headed to North Carolina than to any other state except Texas.

Outside the consulate's gray concrete tower, hundreds of prospective guest workers waited recently from dawn to noon, when the doors close. They lined up for 15-minute interviews at teller-style windows. By evening, they learned whether their visas were approved.

Those approved by the consulate received fresh visa stickers, boarded buses, signed contracts and headed for the border to arrive by nightfall. Those rejected didn't have to pay the $100 visa fee, but received no other refunds and no free ticket home.

Applicants dread rejection.

"We spent a lot of money -- transportation, food, to put the suitcases in lockers in the bus station," said Eduardo, 40, who would not give his last name, afraid of losing the job Bell found for him with a landscaper in Boone, N.C. "I think the company should pay."

Some workers said they considered hiring smugglers. But that would cost at least $2,000 and be far more dangerous.

"This is a risk," said Manuel, 29, who also wouldn't give his last name. "But it costs less money, and at the least you go home safe."

Selective recruiting

Consular guidelines do not address how workers are selected. Bell said he looks for workers with stamina. That often means rejecting women and the overweight, elderly or disabled.

He also won't send applicants banned by the N.C. Growers Association -- those, he said, who have broken their contracts, left early or assaulted co-workers. Their names make up his "ineligible list."

Workers call it la lista negra, the blacklist. They say it contains the names of workers who complained about mistreatment, requested medical attention or challenged employers.

Francisco Acuna, 28, said he got on the list after he was injured three years ago while working in Roxboro, N.C. He said he tumbled off the back of a truck loaded with cucumbers.

He complained, saw a doctor, finished the season and accompanied his crew back to Mexico. The next year, when he applied for the program, he said, he discovered he was ineligible. Acuna tried a different recruiter. He said the man charged $500, took his passport and disappeared.

Now he works in Tepic, about 55 miles from the Pacific coast, making deliveries for a local pharmacy for $50 a week. "You can't eat for that. You get sick and you still have to work, because otherwise you can't afford the medicine," he said in Spanish. "I don't want anything for free. What I want is the chance to work."

Last month, Legal Services of North Carolina sued the growers association and some farmers on behalf of Acuna and eight others. The suit alleges the association's hiring policies violate state laws against blacklisting.

Bell said workers such as Acuna and their supporters want to shut down the recruiting system. But they are misguided, he said. New workers approach him every day. U.S. companies call each week. He already has scheduled more worker meetings and plans to extend his reach as far south as Guatemala.

"If they opened their minds, they would see we are the true advocates," he said of critics. "Sometimes people that have good intentions, it ends up hurting more than it helps."

Former News & Observer staff writer Molly Hennessy-Fiske reported from Mexico through a fellowship from the Pew International Journalism Program at Johns Hopkins University.