Paraguay RPCV Bill Byman and his wife Merarda are foster parents to six children

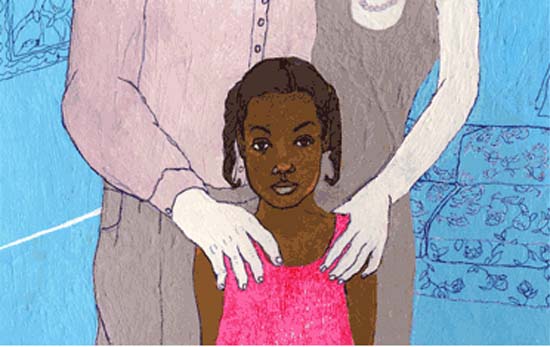

The many cultures of Foster Care

Sunday, May 16, 2004

By KELLY ADAMS, Columbian staff writer

At first glance, the scene around the Byman house is fairly normal for a family of eight. Bill and Merarda Byman watch from their wide deck as six children play in the large back yard.

They are a precious resource for the child protective services agency: a licensed foster family with the added advantage of Spanish language skills.

The family dogs slalom around little legs while arguments erupt over the custody of a soccer ball.

A closer look reveals dark faces next to light ones. The children's ages, four 5-year-olds and two 8-year-olds, also indicate this is a family brought together by something other than biology.

The Bymans are among the few foster families fully equipped to handle a sad result of the growing diversity of Clark County: children coming into care from ethnic minorities. Their different languages, culture even food make the adjustment to foster care even more stressful and bewildering.

Although many families who get involved in the state Child Protective Services system struggle with a lack of trust, caseworkers find recurring issues with some ethnic populations. They include Hispanic children raised to keep quiet about family problems, American Indian children who grow their hair long out of spiritual beliefs, Russian families who are wary of the government.

The Bymans are an example of how children from diverse backgrounds can be successfully placed into foster care.

It helps that Merarda is from Paraguay. The couple met in the South American country when Bill was in the Peace Corps. Both are fluent in Spanish and English. Not only can they communicate with children taken from Spanish-speaking homes, the Bymans are familiar with some aspects of Hispanic cultures.

Simple actions like cooking empanadas can give children the comfort that familiar food brings, Merarda said. One of her foster sons was thrilled as she prepared the meat-filled pastries for dinner.

"My mom made that," the child told Merarda.

The Bymans have one biological child, William, 5, and are in the process of adopting one of their foster daughters, Christina, 5, who is of Central American heritage. Four additional foster children live with them. Two are Hispanic.

Merarda can't have any more biological children but always wanted a large family, Bill explained.

"She wanted five; now we've got six," he said with a laugh.

Growing diversity

The 2000 Census tells the story of the growing diversity in Clark County: a 177 percent increase in the Hispanic population from 10 years ago; a Russian and Ukrainian community that grew to 11,000 in a decade.

The new diversity has brought challenges to the state Department of Social and Health Services, which administers the foster care system. Along with assessing a child's physical health and mental well-being, caseworkers now need to make sure a child's unique cultural background is taken into account.

"This was a much whiter community 31 years ago," said Doug Lehrman, area administrator for the Vancouver office of the state Division of Children and Family Services. He's been with the office for 22 years and lived here for more than 30 years.

The biggest change has been the huge growth of the Hispanic community, making Spanish-speaking staff worth the additional pay the state offers.

A unique challenge in Clark County is the large deaf population, drawn here by the Washington School for the Deaf. That means deaf children occasionally end up in the system. There are a few staff members and families equipped to handle a child who communicates with sign language.

Clash of cultures

Sometimes the cultural practices immigrants bring with them don't mesh with state law.

In the late 1970s and 1980s, Lehrman recalled, the most-represented ethnic minority showing up in the child protective system was Southeast Asians: Vietnamese, Cambodian, Laotian. In those cultures, it is acceptable for children to be left with members of the extended family for long periods or for teenage girls to be put in charge of several young children. Under state guidelines, those actions could be viewed as abandonment, Lehrman said.

The line between acceptable child discipline in the form of corporal punishment and abuse can get particularly fuzzy when dealing with an unfamiliar culture, he said. Lehrman said caseworkers strive to understand different customs, but a line needs to be drawn.

By the protective services' guidelines, "corporal punishment's fine as long as you don't leave bruises," he said.

In some families, including some from other countries, hitting a child hard enough to leave bruises is not considered abusive.

Just because a family's customs differ from American norms doesn't mean the state stays out of it, Lehrman said.

"We still have to intervene. We can't just respect the wishes of the family," he said.

That intervention needs to include a quality assessment, said Bernie Gerhardt, regional diversity program manager for the Division of Children and Family Services. What can look like abuse initially can turn out to be a misunderstanding or easily correctable. Taking a good look at the particular situation can, in some circumstances, prevent a child from being removed from the home, she said.

"It's all in the assessment," Gerhardt said.

Another part of the assessment is determining if the child is a member of any American Indian tribe. Once a child in foster care is identified as a tribal member, it triggers a process outlined by the federal 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act. The act was passed after research showed Indian children were being removed from their homes at a much greater rate than non-Indian children. They were also being adopted by non-Indian families at a greater rate. Every effort is now made to keep children connected with their tribes; that is part of respecting a culture that puts great value on their children and preserving their heritage, Gerhardt said.

Tribal social service agencies are usually more agreeable to a guardianship for a child than a complete termination of parental rights, Lehrman said.

"As far as they're concerned, it's severing a sacred bond," he said.

'You have to be gentle'

Merarda Byman said Hispanic children are usually more shy, take longer to open up and are more stressed when they come into foster care.

"You really have to be gentle with them," she said. Strong extended families are also an important part of Hispanic culture. When all those avenues have been exhausted and a child is placed in a foster home, it can leave the child feeling rejected, Bill Byman said.

"They really feel like they're abandoned when they go into foster care," he said.

The foster care system is frightening for families from countries such as those in the former Soviet Union, where dealing with government can be a scary proposition, Lehrman said.

"They don't trust government at all," he said.

On top of that, the Child Protective Services department is usually not very popular, Lehrman said.

"We're not the most-loved government agency."

With all the challenges, Lehrman said his department benefits from working with ethnic minorities. They have found positive aspects of cultures. The strength found in close extended families is one of those. Currently only one Russian child is in foster care, mainly because placement with a relative is almost always possible.

The cultural diversity offers new perspectives, Lehrman said.

"I see it as something that brings a richness," he said. "It's a major learning opportunity."

Gerhardt said it leads to better work when caseworkers are forced to learn everything they can about a child's culture, not just minority children.

"You really have to improve your communication skills," she said.

The next population that may start showing up in their caseloads are children from Middle Eastern cultures as those populations grow, Lehrman predicted.

"We're not seeing them yet," he said. "I'm just thinking that's the next great challenge."

It's a great challenge to take in foster children but a challenge that is worth the energy and sometimes sadness that comes when children leave, the Bymans said. When Merarda recently was sidelined with a sprained ankle, the children showered her with flowers, stuffed animals and pictures in an effort to make her feel better. Bill said he enjoys being a positive father figure.

"It's an easy way to make a big difference in a kid's life."

Kelly Adams covers social issues and religion for The Columbian. Contact her at 360-759-8016 or kelly.adams@columbian.com.

Did you know?

* It typically takes about 90 days to become a licensed foster parent.

* You don't have to be married, own your home or have a lot of money to be a foster parent.

* Applicants must be at least 21 years old; the primary caretaker must complete first aid, CPR and HIV training, and 30 hours of foster-adoptive parent training.

* Reimbursements for foster families generally range between $366 and $515 per month depending on the child's age, with incremental increases available for children with special needs.

Get involved

Those interested in becoming a foster parent can call 360- 993-7900.