June 27, 2004: Headlines: COS - Tonga: Crime: Murder: Safety and Security of Volunteers: New York Times: 'American Taboo': A Cold Case reviewed in the New York Times

Peace Corps Online:

Directory:

Tonga:

Special Report: 'American Taboo: A Murder in the Peace Corps':

June 27, 2004: Headlines: COS - Tonga: Crime: Murder: Safety and Security of Volunteers: New York Times: 'American Taboo': A Cold Case reviewed in the New York Times

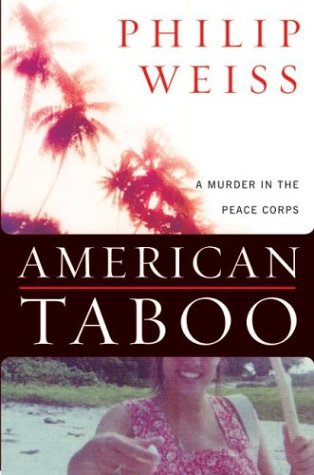

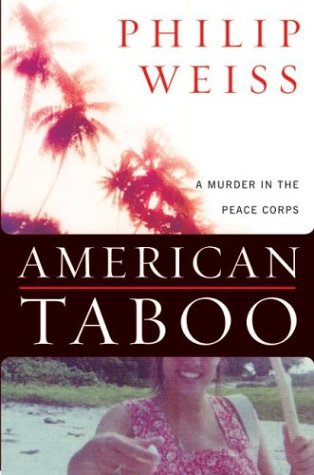

American Taboo: A Murder in the Peace Corps

| Charges possible in 1976 PCV slaying

Congressman Norm Dicks has asked the U.S. attorney in Seattle to consider pursuing charges against Dennis Priven, the man accused of killing Peace Corps Volunteer Deborah Gardner on the South Pacific island of Tonga 28 years ago. Background on this story here and here. |

| American Taboo

Read the story of Volunteer Deborah Gardner's murder in Tonga in 1976 and how her killer has been free for the past 28 years with the help of the Peace Corps. Read an excerpt from Philip Weiss' book documenting the murder and coverup. Then read an essay by RPCV Bob Shaconis who says that Peace Corps' treatment as a "sacred cow" has exempted it from public scrutiny and that the agency has labored to preserve its shining reputation, sometimes at the expense of the very principles it is supposed to embody. |

'American Taboo': A Cold Case reviewed in the New York Times

'American Taboo': A Cold Case reviewed in the New York Times

'American Taboo': A Cold Case

By PETER GODWIN

Published: June 27, 2004

English, it seems, has given many words to the tiny South Pacific nation of Tonga, but Tongan, compliments of Captain Cook, has repaid us with only one -- but what a word: the ''taboo'' of Philip Weiss's title. Ironically it lost its own footing in the Tongan lexicon when the king, in his campaign against phonetic duplication, abolished the letter ''b'' in favor of ''p.'' So in Tongan the word is now rendered tapu. It is, for example, tapu for anything to pass higher than the king's head. Helpfully, His Majesty ascends a small platform during public functions.

It is certainly tapu to kill. Tonga has long since turned away from its blood-drenched past to become the Friendly Isles. There hadn't been a murder there for seven years when, on Oct. 14, 1976, screams pierced the warm, inky Tongan night. Deborah Gardner, a strikingly pretty 23-year-old Peace Corps volunteer from Washington State, was being stabbed to death by a fellow volunteer, Dennis Priven. ''American Taboo'' is the story of how he got away with murder and walks free in New York to this day. To tell it, Philip Weiss has conducted a remarkably tenacious investigation, and has tracked down most of Deb Gardner's colleagues, mining their letters home, their diaries, their unpublished novels and poems. What he reconstructs is a fascinating diorama of life in the Peace Corps in the 1970's, on the edge of the world, four flights and 7,000 miles from home.

Volunteers on Tonga lived a languid island life, putting their bed legs in tuna cans filled with oil to stop insects from crawling under their sheets, passing their leisure time drinking mango home brew, strumming guitars at the Tonga Club, bopping to Santana, Marley and Clapton on a reel-to-reel. News came mostly from the local newspaper, The Chronicle, nicknamed ''The Minute of Silence'' by expats because that's how long it took them to read it. The women learned to pin the hibiscus blossoms on the correct side of their heads when going to church. The men were given a pep talk entitled ''Sex and the Single Volunteer,'' which focused on ''the girls who hung out at Yellow Pier across from the International Dateline Hotel,'' the most beautiful of whom were transvestites, as opposed to the real girls, the fokisis, a corruption of ''foxes,'' so named by G.I.'s in World War II.

By the time the members of Gardner's group, Tonga 16 (they were the 16th Peace Corps contingent to land on the island, where there was one volunteer to every thousand locals), were deployed, most of them as teachers, the glory days of the Peace Corps were well past. No longer did ambitious Ivy League kids see joining up as putting ''a gold star on their resume.'' And with the decline in competition for places, the rigorous selection process -- which initially included a peer review that foreshadowed ''Survivor'' -- was gone. Psychological testing had been dropped too.

So it was that Dennis Priven, a brooding math whiz from Brooklyn with a serious soul, intelligent, sarcastic, muscular, romantically ''oafish,'' seldom without his black-handled, serrated Seahorse diving knife, joined the Peace Corps and arrived in Tonga to teach science and math. When Deb Gardner got there, beguiling but guileless, sexy but wholesome, an un-self-conscious siren to men, Priven began to fixate on her. Indeed, there was barely a volunteer who didn't have a crush on Deb Gardner. One wrote in a poem about her that she possessed all the ''charisma of a pied piper.'' When the tightly wound Priven found his own romantic advances rebuffed, he went to her hut with his knife and a vial of cyanide. He stabbed Gardner 22 times. Then he turned himself over to the police.

Originally intended to be ''missionaries for democracy,'' Peace Corps volunteers are still expected to live with the people they have come to help. This search for empathy extends to a denial of the legal wand of diplomatic immunity. So Priven found himself before the local law. When presented with a conflict of interest between their duty to a dead volunteer (and her parents) and their obligation to help a living perpetrator, the Peace Corps -- from the country director for Tonga, Mary George, on up -- favored the killer. It is this betrayal of trust that provides the main motor for Weiss's crusade. Mary George, a born-again Christian who not long after the killing said she had a vision of someone else, a Tongan, conveniently, stabbing Gardner, asked the police to drop murder charges against Priven. In her cables back home about the incident she carefully avoided the ''M'' word.

Instead, as Weiss laments, it fell to the Tongans to be appalled at the Americans' lack of compassion toward their own dead girl. It was the local kids from Gardner's class who sat up all night on mats outside the morgue where her body lay, singing hymns so her spirit would not be lonely on its journey. And it was they who formed an honor guard along the route her body took to the airport, their faces ''swollen and puffy'' from crying. A local woman ironed Gardner's dress and another bought a pair of pink socks to pull onto Gardner's bare feet, because ''what would her mother think if she came home barefoot? That she had not been appreciated by the people she'd gone out to help?''

PRIVEN'S murder trial was the longest trial in Tongan legal history. But superlatives come easy in the world's smallest monarchy. The trial lasted nine days. It was the first time anyone had ever mounted an insanity defense there. There were no psychiatrists on the island to give expert testimony for the defense, so the American government imported one from Hawaii. (The Tongan prosecution couldn't afford one for rebuttal.) How the interpreter struggled to translate his technical terms to the jury of seven Tongan peasant farmers. The jury's deliberation was also the longest on record. It took them all of 26 minutes to find Priven not guilty by reason of insanity. ALL OF US VERY HAPPY, Mary George cabled back to HQ at the result.

It was left to Akauola, the minister of police with a penchant for quoting Robert Browning, to fight a rear-guard action for justice. He believed that Priven should be incarcerated in the mental hospital on the island, ''on the soil where he spilled blood,'' as was provided under Tongan law after an insanity verdict. But he was outvoted in the cabinet. This permitted the Americans to take Dennis Priven home, with what the Tongans believed to be the explicit understanding that he would be confined to a secure institution for psychiatric treatment. Once stateside, Priven was quickly deemed to be no danger to himself or others, and so he could not be detained against his will, his crime having been committed outside United States jurisdiction. By the time news of his freedom reached the people of Tonga, they could do nothing. They had been duped.

Only then did Mike Balzano, a supervising Peace Corps official back in Washington, conclude that Priven had got away with murdering Deb Gardner. In exasperation, Balzano yelled: ''You mean we can't get him for anything? What about destruction of government property? She worked for us too.'' Priven walked away with a clean resume and got a good job as systems coordinator in the Brooklyn office of the Social Security Administration, which is where the author finally catches up with him.

Their meeting at Dean & DeLuca in SoHo is somewhat anticlimactic. Priven trusses Weiss in an off-the-record pledge before their conversation, little of which the reader is therefore privy to. In that sense there is no closure -- Priven appears to live on with no sign of remorse for having taken another's life. But at least he has now found in Weiss his nemesis -- another man obsessed with Deb Gardner -- who finally exposes this long overlooked stain on the Peace Corps.

Peter Godwin is the author of ''Mukiwa: A White Boy in Africa.'' He is at work on a new book, ''When a Crocodile Eats the Sun.''

Some postings on Peace Corps Online are provided to the individual members of this group without permission of the copyright owner for the non-profit purposes of criticism, comment, education, scholarship, and research under the "Fair Use" provisions of U.S. Government copyright laws and they may not be distributed further without permission of the copyright owner. Peace Corps Online does not vouch for the accuracy of the content of the postings, which is the sole responsibility of the copyright holder.

Story Source: New York Times

This story has been posted in the following forums: : Headlines; COS - Tonga; Crime; Murder; Safety and Security of Volunteers

PCOL12068

13

.

|

By RPCV (user-105n8j7.dialup.mindspring.com - 64.91.162.103) on Tuesday, October 26, 2004 - 9:35 am: Edit Post |

Friends called me this week regarding the Deborah Gardner story which was nationally televised. Some of these friends are heavily involved in Domestic Violence in the United States. It struck a nerve in one of my friends on how Peace Corps staff behaved. She has heard about the many cases where Peace Corps gets it wrong on security issues.

Peace Corps has used this particular Doctor who is very controversial in the pychiatry world and even called a quack by many pychiatrists in Washington DC. This so called Doctor or Medicine man as we know him has been Dr. Diagnose to separate, wrongfully categorize volunteers, stigmize volunteers and fire many others. The Peace Corps and the Congress should do an internal review of this particular Doctor and how many volunteers have been separated from service due to his diagnosis. You could call him Dr. Mengla of the Peace Corps.

Look how he helped Peace Corps in this circumstance. He has always helped them get what they wanted vs volunteer rights.

Insanity is one thing. But, pre mediatation is another. I think we are all smart enough to know what this was. What kind of knife did he have?

No one has questioned Mary George or any other staffers regarding this case.

Its a shame