Peru Photo Exhibit Captures Pathos of 20 Years of War

Peru Photo Exhibit Captures Pathos of 20 Years of War

By JUAN FORERO

Published: June 27, 2004

CHORRILLOS, Peru - At the Riva Aguero house, a rambling, 27-room mansion overlooking the Pacific Ocean, the plaster is peeling, the floors are made of cement and the walls rot. But Peru's past is alive here in riveting, raw photographs intended to recall the horrors of a 20-year terror war.

Advertisement

In the patio, there is a haunting, larger-than-life photograph of a man staring straight into the camera, a heavy woolen bandage covering a bloody machete wound. In a room off to the side, the widows of slain policemen wail, the camera capturing their agony.

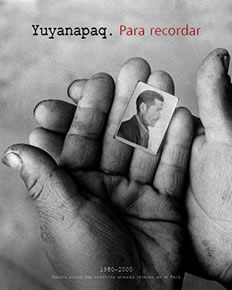

Other stark images hang nearby: an Indian woman gently crying over the draped body of a relative, forlorn Andean mothers whose sons disappeared, a pair of gnarled hands holding the picture of a missing farmer.

What began as a temporary photo exhibit - commissioned by the government's Truth Commission, which issued a voluminous report last August on Peru's war - has become a critically acclaimed and popular museum. Its future financing is uncertain, but the museum has fulfilled the hopes of its creators by becoming a testament to 70,000 Peruvians who perished in the country's long conflict pitting state security forces against two rebel groups, one of them the fanatical Shining Path.

In the process, the 10-month-old museum - called Yuyanapaq, "To Remember," in the Quechua language of the Peruvian Andes, where most of the violence took place - has become an important model for how once-convulsed countries should remember their dark pasts. Though numerous Truth Commissions have operated in Latin America and Africa, none has initiated a museum.

"I think it's one of the best expositions that I've seen in decades, done at a world-class level," said Pedro Meyer, a photographer from Mexico who has studied photographic exhibits worldwide. "Its content, its design, the way the curators set up exhibits, are all extraordinarily good. They have no way to judge the tremendous importance of what they have done."

Nearly 80,000 Peruvians have flocked to the museum since it opened last August, just three weeks before the commission issued its report. Thousands more have seen a traveling exhibition in high Andean cities that were scenes of most violence. The exhibition has traveled to Germany and to New York. In June, it will be seen in Barcelona.

But in a poor country with other pressing needs, Yuyanapaq's future remains in doubt.

Casa Riva Aguero is owned by Catholic University in Lima, whose rector, Salomón Lerner, was the Truth Commission president.

Mr. Lerner, who said he found inspiration in Yad Vashem, the Holocaust museum in Jerusalem, arranged for the house to be lent to the photographers who created the exhibit. The university spent $130,000 on repairs and has paid the $5,000 in monthly upkeep.

The university, though, wants its house back as early as mid-July. The curators, members of the Truth Commission and Peruvian photographers are all scrambling to prod the government of President Alejandro Toledo, which by decree is warden of the photographs, to commit itself to financing a permanent museum, either in Casa Riva Aguero or another locale.

"The state should commit itself to save this, commit itself to saving this idea," Mr. Lerner said.

The Casa Riva Aguero, once owned by the descendant of an early Peruvian president, is in various stages of decay. The rear, where the servants entered, is crumbling. The front, where carriages pulled up to drop off the wealthy, remains opulent with its marble floors.

That is just how Mayu Mohanna, a photographer and chief curator on the project, wanted it. While another curator might have seen an architectural calamity, she saw opportunity in rooms reeking of history.

The back of the house, with its adobe walls and dirt floors, was ideal for vivid black-and-white photographs capturing the conflict in the Andean highlands, where homes are made of mud and the people are Quechua or Aymara Indians. The elegant front, overlooking the coast, was perfect for exhibits on the car bombings and assassinations Shining Path carried out in Lima late in the war.

"The walls are part of the exhibition," Ms. Mohanna said. "The house permits you to see and understand the images. There is a marriage between the house and the images."

The exhibit takes visitors back to 1980, when a small group of Maoist radicals calling themselves Shining Path began burning ballot boxes and mysteriously hanging dogs from lampposts.

What follows, chronologically, are a series of displays containing 245 photos that reflect on victims and victimizers, turning points and setbacks. A video of the war's major events provides context. Another room features the real-life voices of survivors taken from the commission's public hearings.

Each room is carefully tailored to reflect on major aspects of the conflict: the effects on the indigenous, the subversive movement in universities, and the evolution of a bespectacled, frumpy academic, Abimael Guzmán, into the messianic leader of Shining Path.

In one room, an entire wall is covered with the 1982 scene from the bombed-out municipal headquarters of Vilcashuamán, where a diligent worker rolls up a huge photograph of Fernando Belaunde, then the president, after a Shining Path attack.

"It's symbolic because it's complete destruction and amid the rubble a peasant is trying to care for his president," said Nancy Chappell, a photographer and curator who worked with Ms. Mohanna. "It just shows how Belaunde was caught frozen, without a strategy."

The Truth Commission said it wanted the exhibit to serve Peruvians who would never read the dense 5,000-page report on the conflict. "We reached more people than we would have with the report," said Carlos Degregori, one of the commissioners. "It was a way to break this wall of indifference, to reach regions and generations that had not lived the war."