Breaking Ranks in Afghanistan By Sarah Chayes

Breaking Ranks in Afghanistan

By Sarah Chayes, Columbia Journalism Review. Posted December 11, 2003.

A former NPR reporter turned activist discovers the exhilarating power speaking the truth as she sees it. Story

Moved to exchange her role as a journalist with that of an advocate, one former NPR reporter discovers the exhilarating power speaking the truth as she sees it.

"Wouldn't you come back and help us?" The gentle question, almost an afterthought, struck me like the bolt from a crossbow.

It was after dinner with one of my favorite, if sparingly used, sources during the post-9/11 conflict in Afghanistan. Aziz Khan Karzai, uncle of President Hamid Karzai, is a spry gentleman, full of good humor and energy, whose mischievous glance camouflages a penetrating regard upon the situation of his country -- stripped of illusions.

This was in January 2002. I had completed a long rotation for National Public Radio, reporting from Pakistan and Afghanistan. For once I was wrapping up with some kind of dignity, making the rounds and drinking a last cup of tea with friends and contacts. Aziz Khan had invited me for dinner the night before I flew out. We talked about the steep road that lay ahead for fledgling Afghanistan.

After dinner, I got up to leave, and then came his question: "Wouldn't you come back and help us?" My ears heard with surprise what my mouth said without hesitation. "Yes."

Surely it's not just me. Surely all of us struggle with the value of what we do as journalists -- with the impact (or lack of it) of our work on the lives of the people we report about, or on any people for that matter; on the quality of public policy in our field; in short, with whether we, as journalists, help. Surely all of us come to some sort of accommodation -- more or less self-deluding -- with this problem.

Over time, freelancing in Paris, I had come to my own: that given the paucity of foreign news in the U.S. media, just being a foreign correspondent was a kind of subversion. If by the end of my career, I told myself, I had convinced some Americans that the United States is not the only country in the world, I would have achieved something. Reporting for NPR, long a goal for me, further hushed my concerns. But after an exciting period covering the Balkans, beginning with Kosovo, I began to feel the old doubts return. A succession of food stories in early 2001 -- the mad cow crisis, a vegetarian three-star restaurant, an effort by Mondavi to buy out a Languedoc vineyard, etc. -- gave voice to an indictment: "What am I doing? Spending my time entertaining well-to-do Americans with the foibles of well-to-do Europeans." I began groping for alternatives.

Then came Sept. 11. What else would one want to be at that moment than an American foreign correspondent with some experience of the Muslim world?

And yet it proved a difficult juncture to be an American journalist. "The worst period in my entire career," a dear friend confided as we were comparing notes afterwards. He sent me a list of story ideas his editors had turned down. "They simply didn't want any reporting," he explained. "They told us the story lines, and asked us to substantiate them." CNN correspondents received written instructions on how to frame stories of Afghan suffering. A BBC reporter told me in our Quetta hotel the weekend before Kabul fell how he had had to browbeat his desk editors to persuade them that Kandahar was still standing.

It was as though, because the 9/11 attacks had taken place in the American nerve center, they had blown out the critical apparatus of the very people we had always trusted to have one. NPR was not entirely immune. My one civilian casualty story, I hasten to note, which drew vituperative reactions from listeners, enjoyed the full support of my editors. But as time went on, I sensed a rising impatience with my reporting. In that same period between the fall of Kabul and the fall of Kandahar, when the BBC correspondent had trouble with his desk, a senior NPR staffer e-mailed to say that he no longer trusted my work as he had in the past:

A spot I heard tonight was a perfect example. You said that 'refugees' arriving at the Pakistan border from Kandahar described the city as calm, with the Taliban firmly in control. As you surely know, this is the official Taliban line ... You did not point that out. The critical question is whether these refugees are in fact pro-Taliban ... If they are not pro-Taliban, why would they be leaving Afghanistan at the very moment when the Taliban are losing control and anti-Taliban Afghans are celebrating? ... with just a few words you can help the listener put what you're reporting in some context, in order that they understand that what you're sharing with them is just a partial -- and possibly a biased -- account, based on pro-bin Laden sources.

I am a reporter. I try to diversify my sources. They included truck drivers moving great loads of Kandahar's signature pomegranates across the border to buyers in Pakistan. Were those truckers "pro-bin Laden sources?" There had been a withering U.S. bombing campaign under way at the time. In that context, could no one be an unaligned refugee? Mightn't people, regardless of their views, flee their homes under a barrage of fire? And -- a difficult question for Americans to untangle -- was "pro-Taliban" necessarily synonymous with "pro-bin Laden?" I had learned that it was not.

These differences of vision with my own organization, and a growing disillusion with the U.S. press in general -- a sense that it had abdicated its duty to help the public think beyond instinctive reactions -- doubtless played a role in my readiness to receive Aziz Khan's question.

So by March of 2002, I found myself field director (an invented title) of Afghans for Civil Society, an organization founded by Qayum Karzai, the president's older brother, in 1998, but non-existent inside Afghanistan up to that time. The job amounted to inventing an NGO.

We did so with blissful disregard for the usual rules. The firewalls most NGOs erect between development work and political advocacy haven't existed at ACS. And that's why, for me, it works. It's no use deluding oneself. I am not a medic, nor an engineer, nor do I possess any other concrete skill "useful" to people. This incapacity is what held me up when I toyed with the idea of leaving journalism before. What I know how to do, what I do almost compulsively, is look at things, analyze them, and talk about them. Consequently, please understand: I am not attending the bedsides of Afghan mine victims or shepherding a flock of children at an orphanage.

Of course, ACS does run development projects. We rebuilt a village, for example: ten houses and a mosque, bombed to rubble during that final intense battle for the airfield outside Kandahar when the Taliban regime was in its death throes. I visited the building site every day, cajoling children to help clear the debris by making truck noises with them and loading their outstretched arms.

But from the start it was clear to us that humanitarian or development work, conducted in a political vacuum, is at best nonsense. At worst, it can reinforce structures that, if perpetuated, will ensure that aid recipients never get beyond the stage of consuming handouts. In our case, for example, the provincial governor (one of the warlords you've read about) had awarded a monopoly on stone -- which along with sunlight is the only abundant resource in this parched former desert oasis -- to his brother, to corner the market in gravel as construction of a major highway was about to begin. Our tractors, fetching foundation stone for the village houses, were held up at gunpoint. I will spare you the details, but the upshot was a battle with the governor, which ACS, and I, took public.

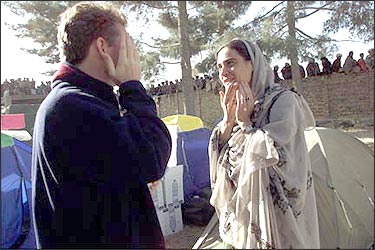

I became an outspoken critic of the prevailing alliance of convenience between the Afghan central government and the international community, and the warlords ruling the provinces. I made my position clear in public and in private. And then, you can imagine how it goes: There's this American lady, right? She's been living in Kandahar, of all places, for the past two years. And she's willing to talk.

I had moved from talking to sources to being one.

What I have found is that the two elements of our work -- development and advocacy -- complement each other indispensably. Without building that village, I would never have known what warlord government means. Our analyses are grounded in intimate hands-on experience. But had we not strived to change the situation of women, the income we provide for 200 of them -- by commissioning and buying the intricate embroidery that is local tradition -- would be next to meaningless. On the day that things blow here -- and they could erupt if poor policies are not reversed -- it will be as if we had never come in the first place.

The trick, of course, is to find the right balance between the development work and the policy stances, so that the latter do not damage our ability to continue the former. This is a balance that we are forever struggling with. Thus, this new role of mine is a hybrid one. But it's not reporting.

Many ask how it feels to put down my microphone. What I have discovered is an extraordinary liberty in being allowed to implicate myself, in being permitted to draw and explicitly voice the conclusions of my observations -- conclusions journalists can only imply in their stories, hoping the public will get the drift.

Sarah Chayes was the Paris correspondent for National Public Radio from 1996 to 2002. She has reported in the Balkans, North Africa, and the Middle East. She now works for an NGO in Kandahar.