When the Peace Corps discovered that their new recruit Peter DiCampo had received first-aid training as a Boy Scout, they assigned him as a medical officer to the village of Wantugu, Ghana. The people there suffered from guinea worm, a horrifying parasite that nests in the body and then bursts through the skin. DiCampo was tasked with helping the village eradicate it. But in the barren scrublands, it soon became clear that the village had an even larger problem on its hands: When the sun went down, Wantugu disappeared into darkness. Wires were strung throughout the streets but there was no electricity coursing through them. For DiCampo, who is also a photojournalist, there would be no e-mail, no television and no phones, and he would have to travel to the nearest town to charge his camera and laptop batteries. A minor inconvenience to a temporary aid worker was a major problem for a struggling agricultural community. For those living in more-developed parts of the world, it can be surprising how difficult it is to progress as a community without this basic service. Especially for a country near the equator where night falls at about 6:00 p.m. year-round. The lack of electricity has impacted education, food production and Wantugu's stunted economy. That was 2006. Now, after eight years of broken promises by politicians, Wantugu is finally leaving the darkness, and DiCampo returned to see what changes may come. Befriending the community over the years, DiCampo has been welcomed into people's homes as the funny white guy who takes pictures, offering a unique opportunity to tell the stories of northern Ghana.

When the Peace Corps discovered that their new recruit Peter DiCampo had received first-aid training as a Boy Scout, they assigned him as a medical officer to the village of Wantugu, Ghana

Out of the Darkness: Wiring a Desert Village

* By Brendan Seibel Email Author

* July 7, 2010 |

When the Peace Corps discovered that their new recruit Peter DiCampo had received first-aid training as a Boy Scout, they assigned him as a medical officer to the village of Wantugu, Ghana. The people there suffered from guinea worm, a horrifying parasite that nests in the body and then bursts through the skin. DiCampo was tasked with helping the village eradicate it.

But in the barren scrublands, it soon became clear that the village had an even larger problem on its hands: When the sun went down, Wantugu disappeared into darkness.

Wires were strung throughout the streets but there was no electricity coursing through them. For DiCampo, who is also a photojournalist, there would be no e-mail, no television and no phones, and he would have to travel to the nearest town to charge his camera and laptop batteries.

A minor inconvenience to a temporary aid worker was a major problem for a struggling agricultural community. For those living in more-developed parts of the world, it can be surprising how difficult it is to progress as a community without this basic service. Especially for a country near the equator where night falls at about 6:00 p.m. year-round. The lack of electricity has impacted education, food production and Wantugu's stunted economy.

That was 2006. Now, after eight years of broken promises by politicians, Wantugu is finally leaving the darkness, and DiCampo returned to see what changes may come. Befriending the community over the years, DiCampo has been welcomed into people's homes as the funny white guy who takes pictures, offering a unique opportunity to tell the stories of northern Ghana.

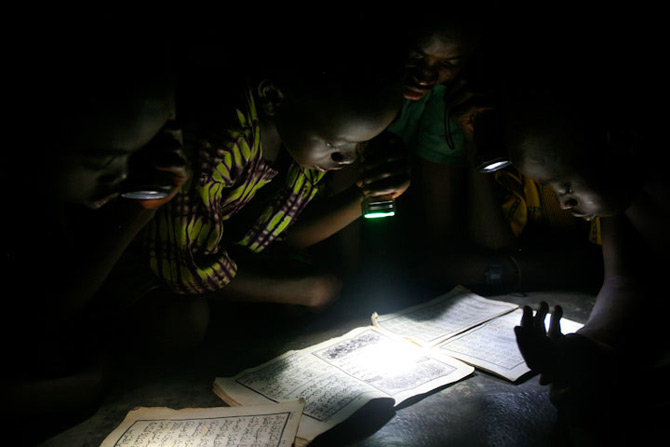

Wantugu relies on farming. Seasons dictate how many students attend class during the day. At night children would collect in mosques sharing lanterns and flashlights to read. Wired lighting now helps students to continue their studies after helping in the fields.

"The teacher says, ‘We can gather at my house now that I have a light'," said DiCampo. "There's a group out there who wants to and recognize it as a way to have more of a future. So I think it makes big difference for them."

Another possible improvement is teacher retention. Until recently many instructors would travel from the nearest city, Tamale, and stay throughout the week. Between the loss of basic amenities and a fluctuating student population, Wantugu experienced a cycle of abandonment. Some changes have taken place on a local level, such as hiring instructors from the immediate area, but being able to court qualified staff from further afield can only improve the children's schooling.

The current Peace Corps volunteer stationed in the village recently arranged for the donation of a computer. A secure room was built in the Junior Secondary School to begin teaching students basic computer skills. While a secondhand PC without internet connectivity may seem inadequate, just being able to introduce children to technology is an exciting development.

"It might only affect the top students of the class," DiCampo said, "but still that's an opportunity for them to come out of that school with a decent education, go to Tamale to further their education, and while they're there to be like, ‘I know how to use a computer.' That's huge."

Ghana does not lack resources. Two dams draw wattage from the Volta River and additional electricity is generated through thermal plants. Enough energy is produced to export surpluses. In Wantugu, power lines hung useless for years. They were installed during fits of vote-courting and then abandoned after the elections.

Work on the electrical system was performed prior to every election cycle. In 2000, the poles were erected, but work ceased after the votes were tallied. This process repeated four years later and threatened to yield the same lack of results in 2008.

Jim Niquette, representing the Carter Center, an NGO operating in Ghana, suggests this ambivalence mirrors disenfranchised communities everywhere. "Wantugu is no more ‘ignored' than the poor urban centers of Africa or someone on the south side of Chicago," he said by e-mail. "Poor people always get disproportional amounts of government spending on infrastructure. Wantugu just happens to be part of the world's poorest of the poor. Therefore little or nothing finds its way to them."

Adam Yakubu represents Wantugu in the district assembly, the governmental body which agreed to purchase the electrical poles on the people's behalf and dictated when work would be done. Powerless to directly enact change, his persistence likely resulted in the project's eventual completion. "I'm willing to bet that every time he saw the district chief executive, he brought up the electricity in one way or the other," said DiCampo.

More than 1,000 villagers congregated in Wantugu last year to see a film and photography project DiCampo presented with filmmaker Alicia Sully.

When DiCampo paid Wantugu a visit in 2008, he found himself attending a ceremonial flicking of the switch. After eight years of growing political pressure and persistence, the district government finally fulfilled its promise to complete the electrical installation.

The most striking change for DiCampo became obvious after dusk. "People spend very little time inside their rooms unless they're sleeping, because it's hot," he said during a trip back to the States. "So everyone's got a light on outside. And they leave them on all night, which I don't understand."

The Delta River Authority, Ghana's private utility company, administers the power and keeps the meters. Whether a community accustomed to buying kerosene and batteries is prepared for monthly bills remains to be seen.

In the late '90s Ghana pushed through electrical-grid reforms to reduce the inequity between the urbanized south and rural north. Private contractors were brought in to build infrastructure, with communities responsible for the cost of poles. Agricultural villages like Wantugu couldn't afford contributing to the project, which left them at the mercy of the district assembly.

Nearly a decade after the first high-tension lines were planted, homes are still being connected to electricity. The health clinic (which had previously employed solar power) and mosques were quickly wired. Individuals are expected to go through the private power company.

"If they did it officially through the Volta River Authority, there was a connection fee that they paid, and they would get it actually connected to a box with a meter in their homes," DiCampo said. "But then from that people have just been jury-rigging wires up to other households. Which they're actually pretty good at."

Villagers trade surpluses of yams or groundnuts for other food, while larger operations export cash crops to the southern cities. Prior to 2008, rented gas-powered mills would run through the night, grinding corn and millet.

Since the arrival of electricity the process has become easier. Flour is finer, and the locals swear it tastes better. People no longer spend hours waiting for their turn at the new mills, and the machines are cheaper to run.

Things have also improved for the few entrepreneurs scratching out a living, such as the local ginger-beer makers.

"They're selling cold Cokes or purified water, and people said that was the big thing," said DiCampo. "Now that they can refrigerate it, they sell a ton of it."

Subtle changes will have the greatest impact. Until recently everyone purchased propane or batteries to power the few electronics they had. As the meters are slowly connected the price difference will become known, and people will have an opportunity to react to billing cycles.

After graduating from Boston University in the spring of 2005, DiCampo worked as a photographer for local papers on Long Island, New York, and Nashua, New Hampshire, before an internship at Agency VII in Paris. Joining the Peace Corps was one way to duck the traditional journalism rat race.

"But at the same time a lot of it was just being drawn to the fact that you get to immerse yourself in another culture for two years and not have to pay a cent to do it," DiCampo said. "When else do you get to do that in your life?"

At the time DiCampo arrived, Wantugu had the second-largest guinea-worm epidemic in Ghana. The incredibly painful condition spreads through drinking water and becomes debilitating when the worms, measuring up to three feet in length, burst through the skin. DiCampo worked at a government-sponsored containment clinic, shooting photos whenever possible.

"You wake up in the morning and you go down to work, being the Guinea Worm Containment Center," said DiCampo. "There are people pulling worms out of small children who are screaming and crying."

Government programs to compensate victims failed. The afflicted were offered small stipends to confine themselves to the containment center, preventing further contamination. Payments ceased when the program was found to encourage intentional infection.

Northern Ghana's aridity exacerbated the guinea-worm threat. To provide an alternate source of water, a bore well was dug outside the village. The Carter Center, working with the Volta River Authority, installed an electric pump which tapped the high-tension lines standing since the beginning of the decade.

Electricity's arrival has obvious benefits, but may fundamentally alter how the community interacts. Bereft of modernity, people used to congregate at night. During DiCampo's Peace Corps tour hundreds would pay a small admission to watch movies on a generator-powered TV. Now people have begun to gather in smaller groups at home.

"Before it was like several hundred people, and they're all screaming and yelling when there's a kung fu fight or a kiss or something," he said. "It was a different experience to drop that from several hundred people to 30 people."

Even so, DiCampo believes the change from outdoor flashlight dances to reclusive TV viewing will take time. "I do think that will be one of the long-term effects and generational effects," he said. "But it's still such a communal society that that's not going to go away any time soon."

Since leaving the Peace Corps, DiCampo moved to Accra and performed freelance assignments for NGOs and news journals. In 2009 he won a grant from the Pulitzer Center for an essay on Kayayo, a group of young girls who leave the poverty of the north to work as porters in the southern cities. Alongside filmmaker Alicia Sully, who had recently completed a film on the same subject, he returned to the northern villages, showcasing photographs and participating in discussions on the issues of labor migration, urban slums and sexually transmitted infections.

When the project came to Wantugu, more than a thousand people attended the screening. Although Wantugu now has electricity, the Ministry of Information provided the project with a generator-powered mobile theater to serve the many other rural communities still left in the dark.

Wantugu relies on farming. Seasons dictate how many students attend class during the day. At night children would collect in mosques sharing lanterns and flashlights to read. Wired lighting now helps students to continue their studies after helping in the fields.

"The teacher says, ‘We can gather at my house now that I have a light'," said DiCampo. "There's a group out there who wants to and recognize it as a way to have more of a future. So I think it makes big difference for them."

Another possible improvement is teacher retention. Until recently many instructors would travel from the nearest city, Tamale, and stay throughout the week. Between the loss of basic amenities and a fluctuating student population, Wantugu experienced a cycle of abandonment. Some changes have taken place on a local level, such as hiring instructors from the immediate area, but being able to court qualified staff from further afield can only improve the children's schooling.

The current Peace Corps volunteer stationed in the village recently arranged for the donation of a computer. A secure room was built in the Junior Secondary School to begin teaching students basic computer skills. While a secondhand PC without internet connectivity may seem inadequate, just being able to introduce children to technology is an exciting development.

"It might only affect the top students of the class," DiCampo said, "but still that's an opportunity for them to come out of that school with a decent education, go to Tamale to further their education, and while they're there to be like, ‘I know how to use a computer.' That's huge."