Once convicted, Sacco and Vanzetti, in a sense, became the property of their supporters and their vilifiers. They provided a noble cause for what The Boston Globe called "the sob sisters, pacifists and Reds." For ordinary Americans, terrified by waves of immigrants, political radicals and the rise of militant labor, they were evil incarnate. The case, Mr. Watson argues, defined a new American fault line. "Opinions on their guilt or innocence soon separated sophisticate from ‘rube,' liberal from conservative and those who feared authority from those who implicitly trusted cops, judges and juries." Mr. Watson devotes some of his most compelling pages to the long, anguished and ultimately hopeless campaign to rally support for the condemned men, to unearth new evidence, to chip away at the smooth facade of injustice. Pleas, motions and appeals proved futile. The judicial system, forming a perfect circle, simply ratified its own errors. At one point, the state's Supreme Judicial Court decided that Judge Thayer himself should rule on a legal writ accusing him of bias in the case. "Prejudice?" he declared from the bench. "There isn't any now and there never was at any time." Outside Boston, as far away as Buenos Aires and Berlin, millions of eyes saw things differently. Mr. Watson sums it up eloquently. "In the judgment of the watching world," he writes, "one American city would stand for America itself, one court case for the universal dream of fairness, two men for all men staring into the naked face of power."

Costa Rica RPCV Bruce Watson's spirited history of the affair, does a great service in rescuing fact from the haze of legend and disentangling Sacco and Vanzetti from the symbols they all too quickly became

Prejudice and Politics: Sacco, Vanzetti and Fear

By WILLIAM GRIMES

Published: August 15, 2007

Precisely 80 years on, the Sacco-Vanzetti case still resonates like a mournful chord. Almost instantly elevated to the status of myth, the trial and execution of the anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti remains one of the blackest pages in the American national story, a cautionary tale of lethal passions fueled by political fear and ethnic prejudice.

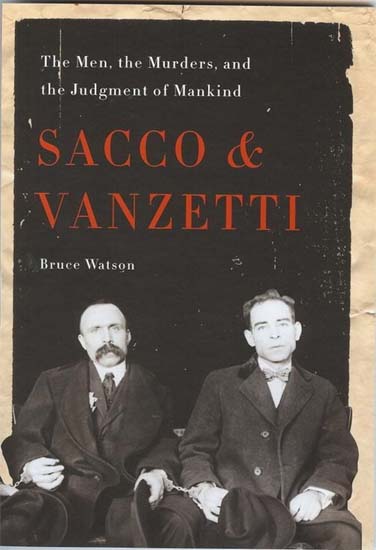

Yet few Americans recall exactly why the two men were arrested, what went on at their trial or why emotions were stirred so powerfully around the world by the plight of two humble Italian immigrants, characterized forever by Vanzetti as "a good shoemaker and a poor fish peddler" in an interview with The New York World. "Sacco and Vanzetti," Bruce Watson's spirited history of the affair, does a great service in rescuing fact from the haze of legend and disentangling Sacco and Vanzetti from the symbols they all too quickly became. It restores immediacy to a wretched series of events that first need to be understood on their own terms.

As the Jazz Age dawned, the United States was a nation gripped by fear, for reasons that feel quite contemporary. Mr. Watson begins his story in late April 1919 with an audacious act of terrorism: the mailing of 30 bombs, disguised as free samples from the Gimbels department store, to a list of prominent Americans, including John D. Rockefeller and J. P. Morgan, and lesser-known political figures known for suppressing radicals.

The plot failed - the bombers did not put enough postage on their packages - but shock waves rocked the country. Class war of the kind unfolding in Russia looked as if it might start up in the United States, a dread reinforced by further bombings and proclamations by shadowy radical organizations that more were on the way. Watching events with grim satisfaction were two dedicated anarchist foot soldiers: Sacco, an edge trimmer at the Three-K shoe factory in Stoughton, Mass, and Vanzetti, a fish peddler in nearby Plymouth. Both men belonged to the Gruppo Autonomo, an anarchist cell in East Boston that favored the violent overthrow of the government. "Sacco and Vanzetti may have been lambs, but they belonged to a wolf pack," Mr. Watson writes.

When two payroll guards were murdered in a daylight robbery in Braintree, Mass., in April 1920, frantic police officers tracked down what they thought was the getaway car. Sacco and Vanzetti turned up a few nights later to claim the car, carrying loaded pistols. The police pounced. The two men would spend the next seven years in jail, protesting their innocence to the end.

No one knows what Sacco and Vanzetti were up to that night. Both told multiple lies to the police. Vanzetti later claimed that he had simply wanted to avoid naming friends and fellow anarchists. Mr. Watson, although highly sympathetic to both men and, like most historians, almost certain that they did not commit the payroll murders, points out that no one can explain what Sacco and Vanzetti were up to the night of their arrest and that, "no matter how much one wants to shout their innocence, questions remain."

They might have been preparing to collect incriminating radical literature from the houses of their associates, fearing raids as May Day approached. This was Vanzetti's explanation. Or, Mr. Watson, writes, they might have planned to hide dynamite, or to prepare for a payroll robbery.

Although the case of Sacco and Vanzetti was quickly taken up as a political cause, the trial itself was not simply, or even primarily, the crucifixion of two radicals. Although the judge, Webster Thayer, was a hidebound reactionary who despised the defendants for their political views and presided with barely concealed bias, the malicious persecution of the two men was as much a matter of bad police work and seething ethnic prejudice as anything else. The jurors, to a man, denied ever considering anarchism as a factor in their decision, and the political views of the defendants were not touched on until late in the trial, and then only vaguely.

Instead, the prosecution paraded a motley lineup of shaky eyewitnesses, most of them pressured or threatened; befuddled the jury with ambiguous ballistics reports; browbeat the many Italian witnesses who vouched for the whereabouts of the defendants on the day of the murders; and, not least, relied on the astounding incompetence of Sacco and Vanzetti's idealistic but badly overmatched lawyer. William O. Douglas, the Supreme Court justice, wrote in 1969 that anyone reading the courtroom transcript "will have difficulty believing that the trial with which it deals took place in the United States."

Once convicted, Sacco and Vanzetti, in a sense, became the property of their supporters and their vilifiers. They provided a noble cause for what The Boston Globe called "the sob sisters, pacifists and Reds." For ordinary Americans, terrified by waves of immigrants, political radicals and the rise of militant labor, they were evil incarnate. The case, Mr. Watson argues, defined a new American fault line. "Opinions on their guilt or innocence soon separated sophisticate from ‘rube,' liberal from conservative and those who feared authority from those who implicitly trusted cops, judges and juries."

Mr. Watson devotes some of his most compelling pages to the long, anguished and ultimately hopeless campaign to rally support for the condemned men, to unearth new evidence, to chip away at the smooth facade of injustice. Pleas, motions and appeals proved futile. The judicial system, forming a perfect circle, simply ratified its own errors. At one point, the state's Supreme Judicial Court decided that Judge Thayer himself should rule on a legal writ accusing him of bias in the case. "Prejudice?" he declared from the bench. "There isn't any now and there never was at any time."

Outside Boston, as far away as Buenos Aires and Berlin, millions of eyes saw things differently. Mr. Watson sums it up eloquently. "In the judgment of the watching world," he writes, "one American city would stand for America itself, one court case for the universal dream of fairness, two men for all men staring into the naked face of power."