It wasn't until I took a road trip with a group of friends several months into my stint that I realized just how vulnerable I was, even with that knife in my pocket. Craving a taste of big city nightlife on our first night in Durban, we took a cab to a trendy beachfront bar district. The siren call of American rock lured us into a two-story bar called Joe Cools. We dug deep into our pockets to buy our over-priced drinks and then sat near a cluster of pool tables. I hadn't yet taken a swig of my beer when I saw a bull-necked Afrikaner shove a significantly smaller black guy to the floor, just a few paces from where we sat. Because the Afrikaner didn't look pissed and the people standing around didn't seem concerned, I immediately wrote off the incident as horseplay. A black employee scurried over to the man's side and helped him to his feet. The guy was barely vertical when the Afrikaner clocked him with a punch that knocked him horizontal again. The sound was unreal, completely unlike Hollywood's interpretation of a punch. Obviously unfamiliar with that adage that admonishes against kicking people when they're down, the Afrikaner booted the guy in his face two, three, four times before starting in on his stomach. He stomped his guts again and again like a boy trying to stamp out every vestige of life in an anthill. I knew that if somebody didn't intervene, I was going to be watching a man kicking a corpse before long. When no one else moved to help, I sprang from my seat and jumped between predator and prey. The onslaught ended after one final kick to the ribs. Ignoring my glare, the Afrikaner barked some orders at the guy who had initially helped the victim. He ordered him to remove the unconscious man from the bar and to clean the pool of blood forming around his head. I noticed just then that the Afrikaner was wearing a Joe Cools T-shirt. The thug was a bouncer. As I glanced around the bar, I saw it for what it was for the first time. Although whites made up less than 10% of the country's population, the only two black people present were the guy on the floor and the man who would soon drag him out the door. We had traveled back in time to the segregated South and hadn't even known it.

J. Elvis Herman writes: When people ask me about my experiences, I share with them both the good and the bad; and when they ask me whether I would recommend Peace Corps service, I tell them that I'm glad I served because I had some eye-opening experiences that have forever changed me, but I also say that I wouldn't do it again

Beware the Half-Truth

February 14, 2011 | Bundu; Kwagga A; Durban, South Africa | Vetting explained

Click to view jabulani9998's profile Posted by:

jabulani9998

Viewed 3,055 times

Shared 63 times

Last updated: February 16, 2011

iReport -

I came to South Africa with Nelson Mandela's Long Walk to Freedom in my backpack and the words of wise men ringing in my ears. "Be the change you want to see in the world," advised one. "Everyone can be great because everybody can serve," said another. "Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country," suggested a third. Much like these sages of yesteryear, the Peace Corps recruiters had had plenty to say about the merits of volunteerism but spoke only sparingly about its perils, and the agency's administrators in South Africa weren't any more forthcoming. I've had a decade to reflect on my time as a volunteer, and I've come to the conclusion that the Peace Corps failed me by consistently understating the dangers of service. I was never naïve enough to believe that living in a developing country would be risk free, but I also never imagined that my service would be so fraught with danger that I would leave the country a year early with a diagnosis of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

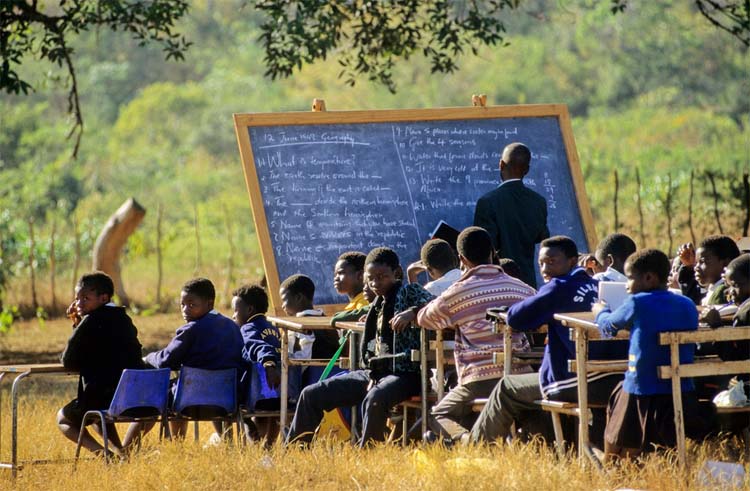

I spent my first three months in South Africa acquiring the language and technical skills I would need for my work as a trainer of primary school teachers. During this training phase, I lived with an Ndebele family in a rural town that didn't have the resources needed for a plunge into the deep end of the 20th century. Bundu did boast a cellular tower that soared above the corrugated steel roofs of the town's mean homes, and a handful of households did have a modern convenience or two, but most of the townspeople were still stuck in the days of pit latrines, community water spigots, and candlelight. I didn't mind the inconveniences of 19th century living, though. Actually, I thrived on the challenge, and it showed. In an informal poll among my fellow volunteers at the end of training, I was voted the person most likely to request an extension of service at the end of my two-year commitment.

I achieved something akin to celebrity status soon after my arrival to the moderately more developed Kwaggafontein, the town that should have been my home for two years. Men waved and yelled my name from a distance when they saw me walking down the street. Women I had never met told me that they loved me in the aisles of the local grocery store. Children lined up to shake my hand. I was bigger than the Beatles-though infinitely less popular than Jesus in that predominantly Christian town-and all because I was the only white guy who had ever lived there. I began to think that the results of that most-likely-to poll might prove to be true.

The honeymoon phase of my relationship with South Africa was short-lived, however. Within a couple months of my arrival to Kwaggafontein, the often brutal realities of life in a country only six years removed from the colonial nightmare that was apartheid began to erode the fantasy narrative that the Peace Corps had helped me construct. I started to hear gunshots every couple nights. One of my volunteer friends narrowly avoided being raped-and possibly killed-by two armed thugs. I sat in the office of one of the schools I served and listened to a woman complain to the vice principal about the corrupt police officers who made it impossible for her to report the gang of men who had raped her ten-year-old granddaughter at gunpoint. In direct violation of Peace Corps policy, I began carrying a small knife on me. I had convinced myself that the knife I brought to the gunfight would keep me safe.

It wasn't until I took a road trip with a group of friends several months into my stint that I realized just how vulnerable I was, even with that knife in my pocket. Craving a taste of big city nightlife on our first night in Durban, we took a cab to a trendy beachfront bar district. The siren call of American rock lured us into a two-story bar called Joe Cools. We dug deep into our pockets to buy our over-priced drinks and then sat near a cluster of pool tables.

I hadn't yet taken a swig of my beer when I saw a bull-necked Afrikaner shove a significantly smaller black guy to the floor, just a few paces from where we sat. Because the Afrikaner didn't look pissed and the people standing around didn't seem concerned, I immediately wrote off the incident as horseplay. A black employee scurried over to the man's side and helped him to his feet. The guy was barely vertical when the Afrikaner clocked him with a punch that knocked him horizontal again. The sound was unreal, completely unlike Hollywood's interpretation of a punch. Obviously unfamiliar with that adage that admonishes against kicking people when they're down, the Afrikaner booted the guy in his face two, three, four times before starting in on his stomach. He stomped his guts again and again like a boy trying to stamp out every vestige of life in an anthill. I knew that if somebody didn't intervene, I was going to be watching a man kicking a corpse before long. When no one else moved to help, I sprang from my seat and jumped between predator and prey. The onslaught ended after one final kick to the ribs.

Ignoring my glare, the Afrikaner barked some orders at the guy who had initially helped the victim. He ordered him to remove the unconscious man from the bar and to clean the pool of blood forming around his head. I noticed just then that the Afrikaner was wearing a Joe Cools T-shirt. The thug was a bouncer.

As I glanced around the bar, I saw it for what it was for the first time. Although whites made up less than 10% of the country's population, the only two black people present were the guy on the floor and the man who would soon drag him out the door. We had traveled back in time to the segregated South and hadn't even known it.

I was returning to my table when the Afrikaner and another bouncer of Neanderthal proportions turned their attention on me. "You got a problem, bro?" asked the second bouncer in a thick Afrikaans accent. He held a cue stick.

"I got no problem, bro," I spat, my brow pinched.

"Then sit the fuck down and drink your beer, bitch."

I don't back down from bullies, but this was clearly a battle I couldn't win, so I swallowed my pride and sat the fuck down.

Before I could formulate a coherent thought, the first bouncer bent over and said something that was totally incomprehensible, so heavy was his accent and so loud was the music. "What?" I asked again and again until I finally understood him.

"Do you support the kaffir?" he had asked.

"I came here to drink a beer, not to watch some dude get kicked to death," I said.

"Maybe you should get the fuck out if you don't like it."

"Let's just go," said one of my friends. It was good advice, given my big mouth. We grabbed our drinks and left.

As we walked down the boardwalk venting and processing, I noticed a group of white police officers walking toward us. I itched to report the beating, but I'd recently seen a news report about a horrific police training video shot a couple years prior showing a group of white officers commanding their dogs to maul two black men, and I didn't have much faith that these cops would see past the victim's skin color. It didn't take more than the shake of a friend's head to convince me to keep walking.

We eventually sat on a retaining wall that separated the beach from the boardwalk. I cast glassy-eyed stares into the Indian Ocean for several minutes before turning back toward the bar. The victim was now lying on his back at the bottom of the bar's outdoor staircase. An ambulance soon entered the scene and parked about a hundred feet from the moaning man; minutes later two police cars parked behind the ambulance. Much like the EMTs, the officers did nothing but talk among themselves. Though none of the paid professionals took any notice of the groaning victim, a group of white teenage girls did. As if playing a game of hopscotch, they giggled and jumped over the man. I wanted to vomit.

I was making a meal of my left thumbnail and shaking my head in disbelief at this display of human indecency when I noticed a red dot on the back of my hand. I shot to my feet and demanded of my friends that we leave immediately.

"What's wrong?" one friend asked.

"There was a red dot on my hand," I said, my voice trembling.

They shared confused looks with one another.

"Laser sighting," I explained. "We need to leave now."

We were in a taxi on our way back to our hostel minutes later. I silently mulled over that red dot for what remained of the night. Was some thug pointing a gun at me to scare me away so I wouldn't talk to the police? Given that the country had the world's second highest per capita murder rate at the time, that's possible but unlikely. My guess is that it was either a laser pointer or a light from the bar itself. I probably jumped to conclusions, but I wouldn't stake my life on it.

I tried to lose myself in my work when I returned to Kwaggafontein. I spent my days in the classrooms working with teachers, while in the afternoons I facilitated workshops or advised community organizers. I was happy most days, pleased to be playing my small role in the rebuilding of South Africa, but no sooner had I shored up my resolve to stay for the duration of my two-year commitment than I would hear or see something that would shake me. One Monday afternoon about a month after my return from Durban, one of the shotgun-toting security guards I had befriended at the town's shopping plaza nonchalantly recounted the weekend's gun battle with the would-be bank robber who had shot him three times in his leg. Weeks later a group of townspeople discovered that two Kwaggafontein men had killed a local taxi driver, so they dragged the alleged murderers from their homes and beat them to death in the street. Days after that I was awoken late at night by gunshots just outside my host family's house. Lying on my belly on the floor of my room, I listened in horror as a man I presumed to have been shot cried out in pain from the street in front of the house. I lied to my family about the violence whenever I called home to hear their voices.

The chaos started to wear on my psyche. I began having a recurring nightmare about three knife-wielding maniacs chasing me down an unfamiliar street and eventually stabbing me to death, and when I stayed with friends in a hostel in Pretoria, they told me that I screamed in my sleep. My fuse became virtually non-existent. When a teacher started talking on his cell phone in the middle of one of my workshops, I gave him an earful in front of the rest of the staff. And the constant attention I received anytime I left the house became maddening. I yelled at more than one child who pestered me for attention. I was clearly losing myself, but I was too proud to concede defeat.

"Go home," said one of my fellow volunteers, a middle-aged woman of Buddhist self-possession who had followed me outside when I walked out of an asinine in-service training exercise at a Peace Corps conference marking the midpoint of our service.

"I can't," I said.

"Why?"

"People are counting on me."

"South Africa is messing you up. You aren't the same person I met a year ago."

"I'm not quitting."

"We're a lot alike, you and me. Five minutes left in the fourth, down by twenty-we're the kinda people who keep playing hard when everyone else wants to quit. But this isn't a game. How's your mom gonna feel if you come back messed up or if she has to claim your body?"

Her words stung, but they might have saved my life. Following several weeks of introspection, I asked the Peace Corps administration to book my flight back to America. After I explained to the head of my host family my reasons for leaving, she nodded and said soberly, "Yes, you must go."

"Um, OK," I said. I didn't want her to drop to her knees and start wailing, but I'd be lying if I said that I wasn't expecting my news to elicit a tear or two.

"When we heard that those men want to hurt you, we thought, Yes, he must go."

"Wait…what?" I asked, thinking I had misheard her.

"Themba heard some men say they want to throw stones at you until you are dead."

"When did he hear that?"

"Maybe two weeks past, maybe three."

"Why the hell didn't you tell me?" I asked, fuming.

"We did not want you to go."

"But you just said you thought I should go."

"Yes, you must go."

"But why didn't you…you know what, never mind," I said, shaking my head in frustration as I walked away.

I left South Africa a couple weeks later with vouchers for a clinical psychologist in my backpack-a Peace Corps doctor had diagnosed me with PTSD at my exit examination-and the words of a wise woman ringing in my ears. "Some causes are worth dying for; some aren't. You need to decide if anyone here will benefit from your death," she had advised. If I had died in South Africa, someone might have named a soccer field after me, but my name wouldn't have become a rallying cry. My death would have been meaningless, and those I had entrusted with my safety would have been to blame.

When people ask me about my experiences, I share with them both the good and the bad; and when they ask me whether I would recommend Peace Corps service, I tell them that I'm glad I served because I had some eye-opening experiences that have forever changed me, but I also say that I wouldn't do it again. If you're thinking about joining the Peace Corps and you want to hear or read about the brighter half of the truth about service, then talk to a Peace Corps recruiter or visit their website. But if you're searching for the whole, unadorned truth, you're going to have to look elsewhere.

-J. Elvis Herman