I went for the same reason that most people my age would have gone. It was during the height of the war in Vietnam, and having just gotten out of college, I had no idea what the hell I was going to do in life. I was an English major, but I wasn't aspiring to be a writer or anything like that, so joining the Peace Corps seemed like a good idea. I actually got married to a fellow Peace Corps member but she was killed shortly after our arrival to Ethiopia by a runaway policeman's car. It was the beginning of the rumblings of the Communist takeover of Ethiopia, which happened a few years later. There were accusations all throughout our training that the Peace Corps was an arm of the CIA, which wasn't true. But there was intense anti-American sentiment going on for sure. Luckily, I was badly injured so I was sent back home. Therefore my experience of Ethiopia was brief and tragic. Once I got back I managed to enroll in a graduate program in the University of Louisville in Humanities. No sooner did that happen than the draft started chasing after me. I mean, I'd managed to defer for a year I think, but then they got me in the end.

Ethiopia RPCV Charles Traub Joined the Peace Corps Peace Corps for idealistic reasons and to avoid the draft

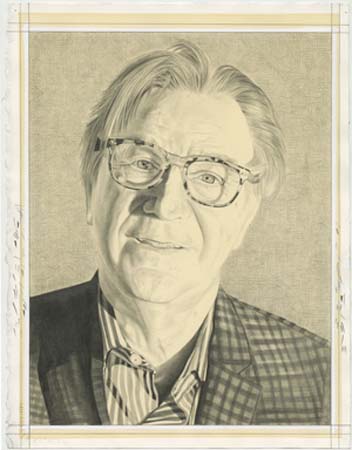

CHARLES TRAUB with Phong Bui

by Phong Bui

On the occasion of his exhibit Object of My Creation: Photographs 1967 – 1990 (February 17 – April 23, 2011 at Gitterman Gallery) the photographer Charles Traub welcomed Rail publisher Phong Bui at the MFA Program in Photography, Video, and Related Media at the School of Visual Arts in New York City, where Traub has been Chair since 1987, to discuss his life and work before an audience of graduate students.

Phong Bui (Rail): I'd like to begin with the front space of the exhibit, which contains landscape images that are depicted with a certain kind of diffused softness, as well as equal distribution of light and dark. More importantly, they are composed frontally to the picture plane. The back room, however, contains pictures of urban, suburban, and rural environments that show more dramatic interplays between light and dark as well as abstraction and representation. Were the two groups of photos made separately? How did they initially come about?

Charles Traub: It was Tom Gitterman's idea to show this body of my earliest work. What you see in the back room, mostly square pictures, were basically done prior to my going to graduate school. As I explain in the catalog essay, I had been an English major at the University of Illinois, and the last semester of my senior year I started working with a camera, which my father left me when he died. I met some remarkable people, and I knew immediately that this was the right medium for me, or at least the right kind of pursuit for me. I was really thrilled, in fact, to have something that I felt so passionate about. All of those pictures in one way or another were influenced by deeply examining everything I could lay my hands on, as well as by keeping up with everything that was going on in the art world. Even though I never had any formal art training, my background as an English major did help me to discover that you could make metaphors or equivalencies of your own experience that were not literal. This was an exciting discovery for me. Initially, those pictures just came out of this understanding that photography is about seeing what the world looks like as a picture. Later, when I went to graduate school at the Institute of Design-where their teaching methodology really emphasized Bauhaus traditions and where they encouraged experimentation-I knew that my life would be changed forever. I remember draping people with plastic as subjects for a photograph, or making lots of solarizations, or playing with contrast as you could in the heavy blacks and use of whites and tonalities that played off each other optically, and where white itself became an object in the picture. In any case, those pictures cover a period of about three years; it isn't much of a sweep relative to my whole oeuvre and my whole practice. But it was an intense one; no matter what, I made pictures every day.

Rail: There is intensity regardless of the differences in subject matter in this exhibit; this is a quite an accomplishment, considering you made these works when you were 22, 23 years old. And how about your choice of formats; the landscapes, as one expects, are horizontal, but then the pictures of the urban and the suburban, rural environment are- -

Traub: Square.

Rail: And in some cases slightly off square.

Traub: Maybe about two or three pictures are not exactly square.

Charles Traub, "Paris, KY, 1968." Copyright Charles H. Traub, Courtesy Gitterman Gallery, New York.

Rail: Did you choose the square because all of its equilateral lengths disallow any thrust or emphasis in any one direction? Malevich, Mondrian, and to some extent Albers made use of the neutrality of that format.

Traub: It was more intuitive, I would say, in both cases. First of all, as far as the landscapes, I don't even know if we really should call them landscapes; rather, they are abstractions of trees that deal with the edge-to-edge problem and the over-all image that becomes the object. Secondly, the square pictures relate to the idea of framing a still life, an idea which I have been using continuously. My latest book is called Still Life in America. Lately, I've been making some paintings, which I've coined "In the Still Life." I think almost any image that gets printed on paper or painted on canvas becomes a still life. And the camera certainly freezes everything into a certain kind of stillness. In other words, those landscapes were an experiment to see how the camera can innately transform an image that has no single object of focus, no one structure that objectifies itself in the picture. They are, in fact, about the intensity of surface that contains subtle tonalities and varieties of edges, or entanglements that allow some kind of emotional connection to the picture as an object, not as a facsimile of anything real.

Rail: Right. And its flatness.

Traub: Of course, because I was interested in both Abstract Expressionist and Chinese landscape's space that have no fixed perspective, where everything that appears is equally distributed on the picture. Indeed, everything is floating.

Rail: That makes sense. Anyway, I noticed a huge difference between two images in the exhibit. One depicts a young boy sitting on the front lawn right in the center axis of the picture which is enhanced by the square concrete slabs before him in the foreground in relationship to another square formed by the interval between his legs and crossed arms. The other is of an older teenager who is lying, sort of sliding off of the picture in the foreground, in the grass; a house looms behind him.

Traub: Yes, the first one was taken in Indianapolis, Indiana, which is its title (1969) and likewise, the second was taken in Paris, Kentucky (1968). This was another lifetime ago.

Rail: The second picture reminds me of Andrew Wyeth's "Christina's World." Although in Wyeth's painting the figure is more central in the landscape, looking away to the house that sits on the edge of the horizon, while in your picture the boy is placed in the foreground, almost sliding off into the abyss below. And he is looking away from the viewer, with the house behind him.

Traub: As far as references to Wyeth's "Christina's World," I would say that I was aware of the painting, as it was one of the most famous images of its day, but whether I was literally thinking about its relation to "Paris, KY" I can't tell you now. You probably recognize the similar sentiment that exists in all of those earlier pictures; they all share a certain kind of Southern Gothic, spooky, nostalgic, and maudlin sensibility. It was part of how I grew up in Kentucky. I also studied a lot of Southern literature such as Wendell Berry, Flannery O' Connor, Faulkner, etc. Those particular narratives were always in my head. The picture of the young boy was taken while I was working at my first job out of college, photographing art at what is now the Indianapolis Herron Museum. It doesn't have the complex yet literal narrative element that the Wyeth's painting has. It's a direct confrontation with the boy as a metaphorical form found by chance on that afternoon when I took it, period. I was certainly more interested in the relationship between how the white body comes forward and black recedes when one uses a two-and-a-quarter square camera. As we all know, it's pretty easy to make a fairly formal, powerful picture by sticking the image in the middle of that square. The trick is to work with the dynamics of the square and the subtleties of how the image is placed, slightly off to its left or right with 1/16 of an inch, like the way Mondrian would do in his paintings. In this case I wanted to float him more or less in the middle. Thus, the contemplative boy becomes a form-a figure, floating in a mysterious abyss. The viewer is thus allowed to bring his or her own interpretation of the photograph depending on what kind of triggers the image incepts them.

I have to say, at that period of my life, Kentucky, Louisville, and central Illinois was the gist of my experience. I hadn't yet gone to Chicago. I think you also have to put into perspective that the practice of photography had been so connected, at least in our ethnocentric perspective until recent years, with American themes, American landscape, the topographic landscape, or the social landscape. The idea of landscape in the photographic modality was so important. There was a great show The Photographer and the American Landscape that John Szarkowski curated in 1963 at MoMA, which included my first teacher Art Sinsabaugh's powerful pictures. His Midwest landscapes are still very original and very powerful pictures. Most of his pictures were about the sparseness and starkness of living on that land, which I knew well. My father was born there.

Rail: Which is where?

Traub: Lincoln, Illinois, which is right in the middle of the state. My father loved every inch of it. I remember when I was a kid my father would drive us from Louisville to Lincoln to see my grandmother, and when we'd get near the border my father would say, "Wow, we're in the land of Lincoln, isn't it beautiful?" I would say things like, "Lincoln was born in Kentucky," or, "How do you compare this barren landscape to those rolling hills with green trees and blue grass in Kentucky?" And he'd say, "Well, you just don't see it." "What do you mean I don't see it; there's nothing to see here," I said. He said, "It's in the horizon." Ten years later I found myself at the University of Illinois and I saw for the first time a Sinsabaugh picture, which basically changed my whole life. I said, "My god, that's what my father was talking about." Sinsabaugh's entire vision was about capturing the narrow space between the sky and the surface.

For your information, Sinsabaugh was a student of Aaron Siskind, whom I later studied with; he became my friend and mentor as time passed by. I met him in the last semester of my senior year in college at University of Illinois. At that point my father had just passed away, and he left me a camera. As I mentioned earlier I didn't want to continue as an English major-or for that matter become a reporter, although journalism was one of my modules taken. Photography and the pure pleasure of its art was what captured my soul. It was a couple of years before I could completely get into it. I went off to the Peace Corps for idealistic reasons and indeed, to avoid the draft. Then, the inevitable happened. I was drafted.

Rail: Tell me about the Peace Corps.

Traub: Oh, that's a tragic and awful story. I went for the same reason that most people my age would have gone. It was during the height of the war in Vietnam, and having just gotten out of college, I had no idea what the hell I was going to do in life. I was an English major, but I wasn't aspiring to be a writer or anything like that, so joining the Peace Corps seemed like a good idea. I actually got married to a fellow Peace Corps member but she was killed shortly after our arrival to Ethiopia by a runaway policeman's car. It was the beginning of the rumblings of the Communist takeover of Ethiopia, which happened a few years later. There were accusations all throughout our training that the Peace Corps was an arm of the CIA, which wasn't true. But there was intense anti-American sentiment going on for sure. Luckily, I was badly injured so I was sent back home. Therefore my experience of Ethiopia was brief and tragic. Once I got back I managed to enroll in a graduate program in the University of Louisville in Humanities. No sooner did that happen than the draft started chasing after me. I mean, I'd managed to defer for a year I think, but then they got me in the end.

Rail: How long were you in the army? Where were you sent? And what was the experience like?

Traub: The army was the worst of the worst. It was a time when they were making a point of drafting college graduates. My whole company was educated and we were all going as infantryman straight to Vietnam. As luck would have it, I was a point-man with a shotgun! But fate was watching over me: two weeks before departure, in a practice battle I was beset with a bad case of diarrhea. I took the wrong medicine and the captain threw me out. I was "back on the block." What luck! I called Aaron Siskind in Chicago and told him I wanted to study photography as a graduate student. He said, "Okay Bud, come on out." And the rest is history.

Rail: When you were studying with Siskind at the Institute of Design, did he ever talk to you about the philosophy of Black Mountain College?

Traub: He certainly mentioned it, but never talked in specifics. I learned more about it on my own later, and it became a model in my teaching. Siskind did talk about teaching, about pedagogical practice, not as a means to teach us how to teach, but as a means to explain why he thought like he did. He loved poetry, Wallace Stevens and Charles Olson. He loved architecture and was enthusiastic about all kinds of technology. He was a thoughtful man-a man about ideas. He taught me that photography was about ideas, not just picture-taking. That was the world that I understood, aspired to, and focused on. It wasn't the photo world of journalists who travel the world. Although we were always a little envious of them. Ours was a world of committed practice to what the camera could do as a creative art form. It wasn't very big. All the 20th century giants knew each other and they were friendly and accessible to younger photographers and people who were interested in their works. I remember going to New Orleans and calling Clarence John Laughlin and saying, "I'm a photographer and I'd like to meet you." And he said, "Please, come!" And the reason they were generous with their time is because there really weren't very many people in the world of creative photography practicing it seriously. Quite similar to avant-garde and experimental films, there just weren't many people doing it and there was practically no audience which would appreciate and support the work. It was like an activity, a practice that was always in the basement or a little hole somewhere. And that's how it was with trying to create or add a photo class in the school's curriculum: It was generally seen as a marginal medium. It wasn't considered very serious. Even at the Institute of Design, a so-called "progressive" institution. Up to a period in the '70s, people like Harry Callahan, Arthur Siegel, and Aaron Siskind were all treated as a bunch of outcasts. But that's how it was during that time. And the few of us who were serious realized that we were not going to be able to continue practice as photographers unless we had a job, and the only job that we really could have was to teach somewhere. And it was very competitive. I remember being beat out, as soon as I got out of graduate school, by Emmet Gowin for a position at Dayton Art Institute in Ohio. It was Emmet's first job, which he held for three years. All of the older generation and mine, from Lisette Model, Berenice Abbott in New York, Henry Holmes Smith in Indiana, Nathan Lyons in Rochester at the George Eastman House were very dedicated to the art of photography. A small number of admirers like me were all passionate about the medium. Out of that passion came an obligation to champion the mission of photography as a creative form. It had to be brought to the forefront, to be recognized as a respectable art form, not to be a footnote in an art history text as it has always been. It needed to become the center of dialogue in the new art world. At present, since that mission has been accomplished, it is hard to remember the collective effort of all who went out and taught at schools all around the country, and now every school world-wide have serious photography programs. We won! We succeeded! [Laughs.] One thing for sure is that the younger generation won't have to struggle with that issue.

Rail: Let's go back again to your early years: you graduated in '71 from the Institute of Design at- -

Traub: The Illinois Institute of Technology, yes.

Rail: Which was the same year that Ralph Gibson's Lustrum Press published Danny Seymour's brilliant book A Loud Song, and, a year later, published Robert Frank's powerful The Lines of My Hand. Were you aware of their works? Or of discourse around them-how, for instance John Szarkowski, the so-called "patron saint" at the MoMA with his strict minimalist formalism wasn't at all generous to Frank's expressive and expansive, engaged responsiveness to social reality?

Traub: Absolutely. I was aware of the splits between those who work in what I now call "real world witness" and those who work in abstracted and fabricated ways. While I work in the former rather than the latter, I can appreciate it all. I don't make any pretense that the photographer is really objective or that he has any handle on truth. A body of work is a synergism and it can make a very powerful statement about a condition-political, social, existential, or purely whimsical. I have yet to find a synthesis of my social visual consciousness and my desire to make an object of art, the latter of which is currently the main focus of contemporary photography. Though subconsciously it is inevitable that it all comes together; what one is, what one sees. I would say that the formal issues seem to be the first thing that come to mind when I take a picture. What results has always been a perpetual struggle to balance some kind of content with camera-seen organization.

And as much as I understand the importance of Robert Frank's The Americans, it never hit me when I was in grad school. I suppose that MoMA didn't anoint it early on also because it was too fuzzy, a bit imprecise, poetic, lacking in the technical and removed objectivity that the "great curator" frequently championed. For me, the work was too caught in its period, it leaned a little too much to On the Road, the Beats, etc. It was more cinemagraphic but nothing wanted to come after it. Yes, I know I'm challenging a pillar of the canon! But in the same light, if you look at Winogrand or William Klein, you'll see a more expansive oeuvre. They really are playing with how the camera sees and how prolific it can be in etching out a fuller experience of witnessing. At the same time, each creating a stylistic identity. In the case of Klein, his pictures served us on many levels, always socially concerned and angry. Confrontational, abstract, and disturbing. Winogrand, on the other hand, holds a bigger political tool but he is whimsical, funny, and always human.

Rail: How did you become director of Light Gallery? And what about your involvement with the Chicago Center for Contemporary Photography?

Traub: Light Gallery was created by a man named Tennyson Schad, a wonderful man who was a copyright lawyer at Time Life, where he met his first wife Fern. They thought, wouldn't it be wonderful to have a gallery that showed all these Life magazine pictures? Which they did, but when they met Harold Jones (the first director) he said to them, Why don't you also show contemporary American photography since there are great young and old photographers out there who don't have any representation? That was how it got started. At any rate, because of my background as an educator at Columbia College Chicago, where I built the department, what is now the Chicago Center for Contemporary Photography, and also because of my relationship with Siskind, Callahan, and others who were represented by Light Gallery, they brought me to New York. Mind you, I was doing color street portraits at that time, which aren't essentially different from my earlier landscapes in that they share confrontation with the surface and filled the frames. And I wanted to photograph in New York no matter what! So being the director of the Light Gallery during that time was not a bad thing. In fact, it was a more powerful job than I realized. However, it was encumbered by many difficulties. The hardest one was that I was an artist while being the director. Needless to say, it created an innate conflict of emotional interest. To be perfectly candid, I suffered because my peers thought of me in those terms, not as the photographer/artist that I thought of myself as. It was a great experience nevertheless because it was the beginning of the boom of photography. The first year we were there, we did a million dollars worth of business. Today, many galleries do that in a week. We thought, my god, this is unbelievable! But, Tennyson was a whimsical man and we spent all that money on expansion. However, we represented many postmodern artists before postmodernism was born. Light Gallery, along with MoMA was the center of the photographic universe.

Rail: Were there specific moments that gave you a sense that photography became legitimate in the '80s?

Traub: We had an opening with Andy Warhol attending (circa 1979), then we went to Studio 54 for a party. It was all glamorous! And even though photography at MoMA was still pretty segregated from the rest of their activities, it at least had its own section. Light was essentially a photo gallery, but we were crossing over and dealing with artists who weren't necessarily straight photographers but were experimenting with the medium and mixing it up with other materials and techniques. i.e.; Chuck Close, Tom Barrow, Robert Heinecken.

I remember Ansel Adams's newly limited edition of "Moon Rise" which sold for $15,000. There were 1,000 of them, approximately. Somebody calculated at that time that the negative was probably the most valuable contemporary art piece in the world because one could create multiples. The "art-gallery world" was tremendously segregated from us and by us; basically it only dealt with photography gratuitously. I remember wanting to bring Warhol, Rauschenberg, Chuck Close, Steven Posen, Ed Ruscha, and several other artists who were crossing over to do a show at Light. And even the staff at Light didn't get it!

I'd add: the medium of photography was championed first by photographers, whether it was Steichen, Stieglitz, Nathan Lyons, John Szarkowski, Harold Jones, or whoever. There were very few writers or curators who knew anything about the creative fine art of photography. Those who did had basically fallen under the influence of other photographers.

Rail: What happened next?

Traub: I left Light Gallery in 1980 and did freelance photography and corporate stuff while keeping up with my own work as well as writing, publishing books, and teaching as an undergraduate senior seminar at SVA and other places. David Rhodes, President of the SVA, called me up one day in 1987 and said, "In addition to the two graduate programs at SVA-painting and illustration-would you consider helping to create an MFA program for photography?" He initially wanted to build a straight photography program with darkrooms and all of those conventions, and I said, "You can't possibly begin a program at this point-without going digital." Because there was already some digital activity in the school at that time around '87 I said to him, "you know, we have to be ahead of the loop; we have to lead it in some way," and he liked the idea. Actually, I later wrote a book on the subject with Jonathan Lipkin, an SVA alum, In the Realm of the Circuit: Computers, Art, and Culture, published by Pearson/Prentice Hall in 2004, which broadly shows the history and development of creative applications of technology and how I saw the digital world as the integrator, the great interlocutor of all creative practices, not just photography. The book reflects many of the ideas and principles of Black Mountain College. It calls for the integration of the arts and humanistic values which are made plausible by the fact that everything can now be reduced to zeroes and ones. It's easier to cross the platforms of our disciplines. I really believe that the digital world is everything that we need to keep dreaming the dream of creativity forward. And we need to understand that there are no borders from one art to the next. Or, for that matter, between the sciences, humanities, and art. We have to look backwards, to know our history in order to move forward. I think we all have to be very critical, sort of looking backwards at the history in order to move forward. We have to find new ways to reinvent images that come from various sources. And that's how I wanted this department to embrace and grow.

Rail: I remember talking to Jonas Mekas and Shigeko Kubota about the Sony Portapak, the CV-2400, made available by 1967, which basically split the film community in half. Those like Michael Snow, Ken Jacob, and others were against it while Jonas, Shigeko, and Nam June Paik all thought of it as a new paintbrush, which makes sense since it fits the same do-it-yourself spirit of the Fluxus artists.

Traub: Today, we have simply electrified the Fluxus idea. In my generation there are many artists crossing many borders; I don't care if it's photography performance, video, poetry, or mapping, it's an image. And I think the political element is always to be considered, "What am I a part of?" "Why?" and, "How can I make a difference/change perceptions?" Narcissism and self-satisfaction are our enemy, not to mention commercialism. As artists, we are all propagating a commodity of sorts. Let's face it, Wall Street is our biggest collector. On the other hand, we're all a part of it because we love the basic idea of nurturing the creative soul.

What we have to remember is it's about looking, after all. And we have to look hard, carefully, and critically.