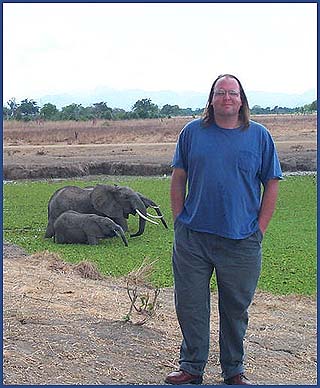

Ethan Zuckerman founded Geekcorps, a sort of Peace Corps for geeks

Ethan Zuckerman: the WorldChanging Interview

WorldChanging Interviews

If you want to know how information technology works in the developing world, Ethan Zuckerman's your man. Zuckerman founded Geekcorps, a sort of Peace Corps for geeks; serves as a fellow at Harvard's Berkman Center for Internet & Society (where he's teaching on digital democracy and exploring how blogs and mainstream media interact to change coverage of developing world issues); works with the Open Society Institute, looking for ways to better connect technology and the developing world; and edits BlogAfrica, the best source of access to African bloggers around.

In his provocative new essay, Making Room for the Third World in the Second Superpower, Zuckerman argues that digital democracy and new media tools will have to undergo profound changes to make a difference in the developing world. It's a powerful piece, one I encourage you to read, one which raises a number of key questions. To get a start on answering those questions, I spoke with Ethan earlier this week:

Alex Steffen: You noted recently on your blog, that the blogosphere has more or less failed on Darfur, that despite serious efforts to organize more blog coverage of the genocide there, there's been little change in focus.

Ethan Zuckerman: Let me temper that slightly. There has been increased coverage of Darfur in the blogosphere, but that that increase has more or less paralleled an increase in coverage in the mainstream media. The people drawing the focus on this have been a handful of courageous people like Samantha Power and Nicholas Kristoff, and the people doing the reporting on this aren't bloggers, they're human rights organizations like Human Rights Watch. People like Jim Moore have done a great job of beating the drum, but Darfur isn't a story that came out of the blogosphere, and it's not a story that was particularly amplified by the blogosphere.

Which raises the question, "In a world full of serious problems, what is this medium that we've created actually good for?"

(more...)

The community of people who blog right now are largely wealthy, white European and American technocrats. The stories that come out of the community and tend to get amplified tend to be stories having to do with having to do with technology and American politics.

Those are the stories people in the blogosphere relate to, like the story of Reverend AKMA getting asked to stop using WiFi outside of a Nantucket public library, which has gone around remarkably fast. Being accused of bandwidth theft is something people can identify with immediately. But issues which fall outside of the immediate experience and concern of the people blogging in some ways actually seem to be harder to talk about in the blogosphere than in mainstream media.

AS: How might we change that?

EZ: I think we get people to tell stories. That's the big lesson we learned with Salam Pax. Once we had someone in Iraq with whom we could find some common context -- hey, we listen to some of the same music, clearly we have a few things in common -- we took a huge step. What was going on in Iraq was happening to someone we had some connection with. We'd probably care a lot more about Sudan if we were hearing more from the actual aid workers and refugees themselves.

But it's not just Sudan. Right now, one of the conflicts everyone needs to be tremendously worried about is unfolding in Burundi, where Hutu rebels based in the Democratic Republic of Congo have crossed the border to slaughter Tutsis in a refugee camp. It's the latest event in a regional war that's been going on since the genocide in Rwanda a decade ago. The war involves, at minimum, Burundi, Rwanda and DRC - and risks almost every other nation that borders eastern DRC.

That actually wouldn't be a hard place to try to get people to blog. Rwanda's got a lot of cybercafes and a lot of pretty technically knowledgeable people. And their perspectives would be incredibly useful. But I'm not sure anyone's actually blogging anywhere in Rwanda at the moment. It's hard for good blogging to appear out of nowhere.

We haven't had our first developing world A-list blogger yet. We haven't even seen anyone in the West who writes primarily, or even frequently, about developing world issues developing the kind of reputation that would help them get the word out on crises like these.

AS: I wonder also if we haven't set up an inadvertent reward system in the blogosphere which makes the emergence of bloggers like that less likely? I know that most of the things we do on WorldChanging that are really good and original don't get picked up by all that many people, but every once in a while we have a story, and it almost always involves technology, that gets picked up everywhere. It's really hard not to be lured into feeling, Well, that's what people want to hear about --

EZ: You've actually just identified the essential problem of free market journalism. In free market journalism you're allowed to print whatever stories your audience wants to read. And because you know your audience is more interested in Michael Jackson than Jesse Jackson, you're going to run fewer stories on policy and more on the abuse of boys on Neverland Ranch. Unless you get some extremely strong current of countervailing opinion, your coverage tends to fall towards the lowest common denominator. That's why the international news hole in domestic television coverage has shrunk to almost nothing in recent years. The assumption is that no one's interested.

That's why a blogging community that pays attention to the rest of the world is so important. If bloggers talk about what's happening in Africa, say, that not only means that more people have access to information about what's going on there, it also means that there's a countervailing force which shows the editors at the New York Times that people are interested enough in these issues to read about them.

AS: The best-read bloggers today are almost exclusively folks who are or have been involved in the business of technology in one way or another. But I wonder if, given the sheer number of people who are coming online and starting blogs and starting to communicate, parallel A-lists might not be possible, composed of people whose spheres of concern are different? Is the focus on technocratic concerns written into the blogosphere's DNA?

EZ: That's one of the most interesting questions we're looking at.

Look at what's gone on with Brazilians and Orkut. If you look at new Orkut memberships over the last few months, they've been overwhelmingly coming from Brazil. Spend any time on Orkut and you largely find Portuguese speakers, which is driving the English speakers nuts. What was supposed to be a social networking service for wealthy American technocrats is becoming a social networking service for wealthy Brazilian technocrats.

So we know that we can change what language is being spoken and to some extent the nationality of the technocrats involved. But it's not all clear that we can change what we talk about. That is, demographic shifts in the blogosphere may be easier than psychographic ones.

AS:So how do we change what we're talking about?

EZ: Well, I think we need to change who we're talking with, and that takes building new kinds of bridges.

One of the kinds of bridges I'd like to build is between talk radio and blogging. For much of the world, talk radio shows are their blogs: you have something to say, you find a platform to say it on, lots of people can hear you say it and they respond to it. Encouraging people to blog in Ghana is all well and good, but at the moment, most of the interesting debate there is happening on talk radio. (And here we need a quick shout-out to Christopher Lydon, former host of The Connection, who has been plugging this idea for some time now.)

If we could connect the two, it might change the nature of both media, but building a cross-over medium is non-trivial. At the moment a lot of it is just technological. It's pretty unrealistic to expect people in most parts of the world to set up Moveable Type. Heck, for that matter, in a lot of the parts of the world that I work in, just getting people enough experience with computers and the minimal expertise to use Blogger would be a pretty big deal. This stuff is still pretty hard for folks.

AS: The tendency has been, in the developed world, to point to two main developments as indicators of the emergence of the Second Superpower: online organizing, like MoveOn and the Dean Campaign and the rise of blogs. Might there be a different set of criteria when looking for signs of the emergence of the Second Superpower in the developing world?

EZ: If what we mean by Second Superpower is that bottom-up can work as well as top-down and that technology can go a long way in enabling this, then yes, I think you have to look for very different things.

One of my favorite examples has to do with election monitoring in Ghana. In Ghana in 2000 we had a pretty critical presidential election. The leader who'd taken power in 1979 was stepping down. For the first time an opposition had a chance to stand and there was widespread fear -- for good reasons -- that there would be election fraud and intimidation.

The coping strategy that everyone came up with was fascinating. It basically involved cellphones and talk radio. What happened is guys would go out to polling places with their cellphones, they'd see someone obstructing access to the polls, and then they'd call a talk radio station and describe what was going on. That put enough pressure on the police that they had to show up and investigate. It proved remarkably effective.

I see that very much as a Second Superpower type of behavior. And I think techniques like that are spreading quickly. But as far as having a forum for global debate about what we want the world to be like, I don't see a huge amount of that happening. And until it does, I don't think the Second Superpower will have much in the way of an ideology or be much of a political force.

AS: You mention in Making Room the usefulness of technology in fighting corruption, avoiding censorship and protecting human rights. You imply that technology can help developing world nations find their way to democracy. How can technology help that process?

EZ: I guess that's not exactly where I'd hang my hat on the subject. Right now you have the Bush campaign running around saying that we had 40 democracies ten years ago, but we have 120 now, but the truth is a lot of those are fictitious democracies. There's the shell of a democracy, but while people may have the vote, the process has been so effectively subverted that the will of the people almost doesn't matter.

It's pretty hard to expect technology to turn non-democracies into democracies. Where I think technology can make a huge difference is where you have a young and fragile democracy. In those cases, I think what helps is finding ways to empower individuals.

Empowering individuals, for example, to avoid systematic corruption -- that's the kind of project which has leverage. Put the customs service online. Customs is a place where there's an enormous amount of corruption, where goods come in the door and lots of money changes hands under the table. If you can put that system online, it becomes much harder to subvert. When the whole thing is on paper, it's easy for a corrupt official to charge you money for the stamp or refuse to process your invoice unless they get a bribe. When it's all online, it's much easier to say, here's my money, here's my form, where's my shipment?

AS: You can make the systems transparent?

EZ: That's what the focus has to be: finding systems in young democracies which aren't transparent, and putting them online in a way which encourages public review. Public bidding for government contracts is an important one. Procurement procedures, which are hugely important in developing world governments and where graft is common. Put these online, and when someone who isn't related to the prime minister loses a bid, they can make a stink about it to the press.

Tackling the property rights system is another example. Take all the land deeds and putting them online, so that people can get clear title to their land as Hernando de Soto suggested we have to do. That's a hard problem. It's a hard problem technically and its a hard problem legally. It's still pretty rare to see big efforts like that taking place, but that's where the really exciting possibilities for strengthening democracy can be found.

One of the challenges in all of this is that it's next to impossible for new governments to take this on by themselves. In many cases, governments are going to take this on when multilateral aid agencies come in and make it possible financially. Then you end up with a really complex allocations problem. In a world where we're trying to deal with HIV/AIDS, where we're trying to undertake reconstruction in Afghanistan and Iraq, where we're dealing with famine and war, where does putting up a really good property system for Senegal fit in?

AS: And yet, fighting corruption would seem to be pretty vital in making head-way on a bunch of other more drastic problems.

EZ: It is, but it's not just corruption we're talking about here. It's corruption when you're a shopkeeper trying to get your shipment of widgets in and the guy won't let them through unless you pay him a thousand dollars under the table. But it's not corruption when you're a farmer and you're trying to buy a piece of land and literally no one knows who owns it. That's just incompetence and bureaucracy and the challenges of dealing with legacy systems. In many developing nations, those challenges are at least as substantial as the problems of corruption.

You get rid of corruption by getting a government that understands that the consequences of corruption. Look at what's happened in Kenya, where it's clear that unless Kenya can address corruption in a reasonable fashion there's real danger of fiscal crisis. President Mwai Kibaki was elected on a platform of

promises to eliminate corruption -- but people are growing increasingly frustrated that so little progress has been made.

But these larger issues of efficiency in government and transparency and legal systems which work -- they're essential, but I don't know that anyone has much of an idea of how to go about fixing them.

AS: If you go back ten years or so, there was this real sense out there, at least among the hand-waving crowd -- of which I often count myself a part -- that censorship and human-rights violations were almost solved problems, that maybe we hadn't quite caught up to the technology yet, but that with the Net there was just simply no way that a country like China was going to be able to keep its people down with secrecy and censorship, and that in a world of video camera, cellphones and satellites, horrors like the El Salvador death squads were things of the past. That idea doesn't seem to have worn well.

EZ: You're absolutely right. What we're finding is that the rest of the world is much more complicated than we thought it was.

Look at censorship in China. What we're seeing there is that you have huge numbers of people getting online, it's much harder to have the same kind of command and control over the Internet in China that you might have had five years ago.

On the other hand, the PRC is also investing enormous amounts of money in technology, buying what are essentially intrusion detection systems, very sophisticated firewalls that can look packet-by-packet at what's coming through, find specific content and screen it out. The government's become as effective an adopter of technology as the masses.

We tend to think of information technology as inherently and essentially democratizing. It's not. A lot of it comes down to who gets the tools first. When it's the activists and the artists and the kids, the technology looks and behaves one way. When repressive governments catch on, and realize that they can use these tools, too, very different things happen.

AS: At our global scenarios meeting a few weeks ago, we had a discussion about the explosion of the Nigerian film industry and the incredible work being done by groups like Witness. People are doing incredible work at the scenes of conflict and oppression, to create the kind of images that it takes to move public opinion. If you live in a place where a warlord, mafia boss or dictator is making life very difficult, having the ability to visually document the abuses that are going on is invaluable, and there have never been more tools for doing just that. At the same time, sooner or later those warlords are going to catch on that these tools cut both ways. How long is it going to be before we start seeing the developing world versions of Triumph of the Will, with digital video filmmakers extolling the virtues of the local dictator?

EZ: We're already seeing that. If you look at the situation in Sudan, it's very clear that the Sudanese government has been hiring pr professionals for decades to try to figure out how to deal with its public relations problems. And while you've got lots and lots of people standing up and saying Sudan is a genocidal regime, go online and you'll discover tons of websites essentially arguing the contrary. Trace those sites to their roots and you find they belong to a small number of organizations who are tied to a Sudan-American or Sudan-UK "friendship" organization of some sort or another.

The same sort of grassroots techniques we're trying to use to get people to talk about and organize about these issues are getting used by dictators. I'm quite certain that if we dropped 40,000 video cameras on Darfur and set up high-speed Internet uplinks, we'd simultaneously have people making films about how horrible the conditions are in the camps and the Sudanese government going around filming smiling happy refugees. With these technologies, whoever gets there hand of the switch first gets to decide what they get used for.

One of the things that happened in China that shocked people the most was when China started blocking Google and redirecting to Chinese search engines, because there was a recognition that technology had gotten to the point where if the Chinese government had wanted to get slightly more sophisticated they simply could have pushed people towards propaganda.

AS: And if you go online in China and say the government needs to be changed, you're likely to wind up in jail. But that doesn't mean that there's no discussion of reform in China. Xiao Qiang, the UC Berkeley Journalism professor, made the point to me that precisely because the Chinese government can censor the whole Net, there is a new forum for civic dialogue emerging in China, but it's emerging very tangentially and swaddled in discussion about other topics. He says that Chinese Net users are become very astute about having political conversations in non-political terms.

EZ: That's a great example of how different cultures work in different ways with these technologies, which is something entirely too poorly understood in America.

AS: The strength of many of the tech bloom technologies in which folks like us tend to put our faith is based on the power of networks. We tend to forget that networks are only secondarily about connecting machines. I wonder the extent to which many of our problems reflect not the limitations of the technologies themselves, but our limited abilities to form effective international networks of people and build new conversations?

EZ: We tend to get obsessed with the networky aspects of things, and I think for the large part its because we're incredibly disconnected Americans. To me, the whole notion of the social software movement seems this strange, profoundly disconnected, urban, alienated 21st Century phenomenon. The notion that we're so detached from our communities that we need to go online and iterate our friends in order to put ourselves in a community context again -- that maps really badly, if at all, to most of the rest of the world.

AS: Do you see signs that we're getting better at the human side of innovation?

EZ: Slowly but surely we are. What we're increasingly all discovering through the world of Open Source development, is that an approach which thinks of the people who create the tools and the people who use the tools as different groups of people is probably the wrong way to go about developing anything. What you really want to do is figure out the people who are going to using the tool and work with them to create it, and that takes building relationships.

Unfortunately, at this point, that pretty much guarantees that certain kinds of tools will come into being -- because some people are ready and willing to participate in that process -- while other more needed tools won't, because the people who would use them aren't. If you want to build a tool that will be useful for political activism in Central Asia, you'd damned well better have some Central Asians involved in the process. But at this point, that sort of inclusion is just not happening. There's a little more sophistication on the part of people who develop software for the developing world, but not a lot more. More often what you get is an American company saying "We've created a solution for the developing world and now they can use it." That's dumb. That's really, really dumb, and depressingly common.

This is why it's so important to build up software authoring [?] populations around the world. To get this stuff to actually work, you have to do some sort of joint, collaborative design, where you get people from different countries coming together to create solutions. You need people who understand who understand the local problems and also have the skills to write the code. It's not like Microsoft is going to release a new KiSwahili version of Windows and all of East Africa's problems are going to go away. The problems take new code, not just new translations.

AS: This is the key point behind the idea of redistributing the future. Software now runs much of the physical world. If you want to run a power grid, even a distributed one, you need software. If you want to run a modern hospital, or a cellphone network, or a airport, or to design new medicines or new crops, you need software. And the software needs of developing world countries are often quite unique. But the way folks in the developed world have often gone about trying to help is by saying, "Here's the future -- why don't you adopt it?"

EZ: That's absolutely true. That's absolutely true! It's very much a push paradigm. Look at people's explanations of why it's important to bridge the digital divide: lots and lots of people are saying if we could just get the Internet to the people in Kenya they'd be able to use all the breakthrough health information we're coming up with, they'd be able to get crop information and make more money, and they'd be able to get great information on HIV/AIDS -- in other words, they'd be able to consume the information we're building in the West.

This approach fails to understand what's interesting about this work. What's interesting about digital technology is not just that it lets you create tools and hand them out to large audiences, but that once you figure out how to use those tools you're able to build new tools for your own local, specific purposes, but in ways that contribute to the rest of the world as well. It's not just about getting computers into hospitals and schools. What it's really about is ensuring that we have software developers all over the world who can help those doctors and teachers design the tools they need.

AS: How can WorldChanging readers help? Let's say I want to figure out how to get involved: what's your syllabus for Effective Participation in Technological Choice in the Developing World 101?

EZ: A lot of it's just coming into being right now.

Aspiration Tech is essentially trying to put together a collection of what they're calling social source software. The idea is to figure out the best of what's out there for people who want to, say, run a human rights database, and look at who it's available to and what sort of work needs to be done to move it the next step. It's all well and good if there's a great political activism tool that only exists in English, but perhaps it'd be really useful to have it in Spanish and French and Arabic and so on. This is a great way to line smart people up with opportunities to put their talents to work.

Over a longer term, we're hoping to identify some of the most important unsolved software problems. I'll just sort of throw one out: I think that interactive voice response systems are maybe the most critical information technologies needed by the developing world.

Recognizing that in a lot of the world we have low rates of literacy, and that paper-based or even screen-based systems don't work all that well, but that cellphone penetration is incredible everywhere in the world, being able to build really good interactive voice systems is a vital means of connecting people and information. Press one if you want to hear this in KiSwahili, press two if you want to hear this in Songo, enter a code to tell us where you are and we'll give you the weather report for the next week, press three if you want to know what the price of maize is in Nairobi this week. The tools really aren't thereyet, as open source tools. Voxiva has pretty badass IVR tools for the developing world (disclosure - I'm an investor); and there are other commercial tools, but it's very hard to build an open, free solution at this point.

I'd like to see a lot of open source hackers start getting involved with projects that aren't just the next KDE desktop widget but could have powerful implications for large numbers of people. Some of the needed work has to do with new tool creation, but a lot of it has to do with localization, a lot of it has to do with making existing tools work on lower-end systems, a lot of it has to do with bundling and making things smarter and easier for people to adopt.

Another huge thing that I'd like to see more people working on is starting new conversations in the blogosphere. A lot of what I'm spending my time on right now is reading and trying to edit a news feed of about 200 African blogs, trying to get a sense for what are the things going on in that community that'd be interesting to the larger blogosphere, and pulling those out. One thing I would love to see is bloggers adopting each other, saying, this is interesting, here's a blogger writing well about Kenya; I'm going to start reading them regularly, plugging their stuff and introducing them to my community of people.

What's gone on Iran is so interesting, where you have a blog community that had built itself up locally to the point where there were 60,000 people listening to each other and then you have Hoder standing up saying Wait a second, we're just talking to each other. Some of us have to start blogging in English. Some of us have to get heard by the rest of the world.

If we could get the US and European blog communities committed to listening, what could we do with that energy?

AS: This is something we've really been kicking around at WorldChanging. It's our sense that there's a whole mess of people out there doing incredible work out there, work which would benefit from more exposure and work which would benefit the world if more widely known.

EZ: I'm certain that's true.

AS: And, as Wendell Berry said, "To work at this work alone is to fail." People can learn much from people working in other fields. Someone working on hunger can learn a lot from an innovative approach used by someone working on urban design and affordable housing. Those are the kinds of connections that aren't made well --

EZ: But we're in a new enough medium that there aren't yet the fifteen required reading blogs on a subject like environmental chemistry. That means a great deal of opportunity to build targeted generalist media, to do precisely what you guys at WorldChanging are doing and say we're interested in environmentalism. we're interested in political activism, we're interested in human rights, and we're interested in where these things cross over. That makes it possible to draw new connections that mainstream media might miss.

It's also a place where the digital nature of all this stuff becomes handy. We Google stuff because we don't read from the front page to the back page anymore. So when you guys are saying new things that might be important to a specific set of readers, it's going to get found at one point or another.

My concern though, is who's reading and who's writing.

AS: We get readers from all over the world, and that's fun. But the kind of people who are more actively involved, commenting, sending us suggestions and so on, are pretty much entirely from the West. We've had a hell of time finding contributors who are interested in changing the world, have a track record of blogging or writing in English, and who live outside the developed world. With one exception, everyone on our team lives in the US or Western Europe. That's not because we don't want to have contributors from Africa, Asia and Latin America.

EZ: Your challenge is perfectly representative of the blogging world as a whole, though. The few countries which have come on board outside the US and Western Europe have primarily done so in their own language. There's a good Polish blogging community, a good Persian community and a pretty sizable Portuguese crowd, but these still represent the smallest fraction of bloggers.

Which makes me a big believer that this virtual stuff needs more of a physical component. We need to be getting on airplanes and going out and finding people in countries which are poorly represented, who are already community leaders or interesting thinkers, and figuring out how to get them into the dialogue. But people who can blog well across cultural lines are rare. They need to be natural bridge-builders, to have one foot in each culture, to be bilingual or multilingual, but most of all, to be people who can understand enough about their own culture to make it understandable to people from outside of it.

AS: We need a new generation of bloggers?

EZ: Absolutely. Blogging is an elite technocratic culture. My guess is that just being on the Internet doesn't turn us into global citizens, that we need a different kind of conversation. We need people who can build bridges between that culture and the situations in which most of the rest of the world find themselves, which are very, very different. We need to identify individuals, help build up their own blogging communities, and get them meaningful coverage from folks like you guys on the outside who can tell their stories. Once we get to the point where the majority of the top 100 bloggers on Technorati aren't Americans, we'll be ready to have an entirely different conversation.

Those folks aren't out there now. We need to help find them. And it's going to require a more concerted effort than just sending out a lot of email and looking at a lot of websites and hoping that someone shows up. It takes advocacy work to get the tools into more hands, and tool work to make sure the right tools are available, and community work to make sure that someone is listening when they talk.

But that's worth doing. I think more and more that one of the big root causes of many of our problems is just lack of understanding. If we had a clearer sense for what people in the developing world thought and felt and what things were priorities to them and what things were difficult for them, it would be much easier for the rest of us to make a real difference. We've got income gaps and technology gaps, sure, but ultimately, I think the attention gap is the biggest of all.