"I became a teacher in Africa and my whole life changed. I was happier, I had a purpose, and no one ever asked me, "What are you going to do with your life?" I had left home. I was becoming the person I wanted to be, not just a young man with a job but someone developing a sensibility. I had volunteered because I wanted to know the world and myself better. The route from New York to my destination, Nyasaland, took in Rome, Ben-ghazi (Libya), Nairobi, Salisbury (Rhodesia), and finally the tiny aerodrome at Blantyre. Flying low into that last stop, I could see tiny thatched-roof mud huts surrounded by banana groves and maize fields. This sight lifted my spirits. The thrill was intensely like being on another planet. In some ways it was just as remote, a parallel universe, but I thought of it as my Eden. It was December 1963, and I was glad to be gone. I'd been dismayed by the spirit of the times, the violence, the complacency, the racism, the militarism, the weird quest for material goods. I was well aware, with a lightness of soul, that I was unburdened. Everything I owned in the world fitted into the small suitcase I had with me. I had nothing in the bank, no property; did not own so much as a chair. I was superbly portable. I had just turned twenty-two. That first departure for Africa led me to a lifetime of travel. It shaped the way I see the world and showed me that there was more to write about than my own inner miseries. I realized that what at first seemed so alien-a schoolhouse of barefoot students at the end of a red clay road-was not so different at all. Wishing to express this experience, I became a writer. Although I joined one of the earliest Peace Corps groups to go overseas, I was not heeding the call from President John F. Kennedy. Apart from being a coastal New Englander, as he was, I felt I had nothing in common with this remote figure or the complexities of his ambitious and ruthless family. I joined instead partly because the Peace Corps was committed to helping people who were at last free from colonial control. As for the rest, it was a leap in the dark. Author Paul Theroux served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Malawi in the 1960's."

Paul Theroux writes: Obama, the Peace Corps, and the Lesson of My Life

Paul Theroux: The Lesson of My Life

Yes We Can!

In 1963, Paul Theroux joined the Peace Corps, shaping both is future and his view of the world: Cue President Obama's new appeal to public service...

I became a teacher in Africa and my whole life changed. I was happier, I had a purpose, and no one ever asked me, "What are you going to do with your life?" I had left home. I was becoming the person I wanted to be, not just a young man with a job but someone developing a sensibility. I had volunteered because I wanted to know the world and myself better.

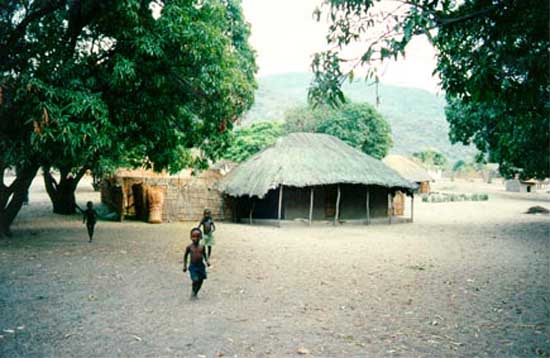

The route from New York to my destination, Nyasaland, took in Rome, Ben-ghazi (Libya), Nairobi, Salisbury (Rhodesia), and finally the tiny aerodrome at Blantyre. Flying low into that last stop, I could see tiny thatched-roof mud huts surrounded by banana groves and maize fields. This sight lifted my spirits. The thrill was intensely like being on another planet. In some ways it was just as remote, a parallel universe, but I thought of it as my Eden.

It was December 1963, and I was glad to be gone. I'd been dismayed by the spirit of the times, the violence, the complacency, the racism, the militarism, the weird quest for material goods. I was well aware, with a lightness of soul, that I was unburdened. Everything I owned in the world fitted into the small suitcase I had with me. I had nothing in the bank, no property; did not own so much as a chair. I was superbly portable. I had just turned twenty-two.

That first departure for Africa led me to a lifetime of travel. It shaped the way I see the world and showed me that there was more to write about than my own inner miseries. I realized that what at first seemed so alien-a schoolhouse of barefoot students at the end of a red clay road-was not so different at all. Wishing to express this experience, I became a writer.

Although I joined one of the earliest Peace Corps groups to go overseas, I was not heeding the call from President John F. Kennedy. Apart from being a coastal New Englander, as he was, I felt I had nothing in common with this remote figure or the complexities of his ambitious and ruthless family. I joined instead partly because the Peace Corps was committed to helping people who were at last free from colonial control. As for the rest, it was a leap in the dark.

Today, we live in a world much like the one I knew as an absolute beginner, more than forty years ago. Technology is brighter now, but so what? Bewilderment persists, we're as fallible as ever, and most thoughtful people, especially the young, have the same question: Where is my place in the world?

Once again we have a president who is calling on us to engage with our community and the world. Just as then, we face war and violence-this time in Iraq, Afghanistan, and the Middle East. What's new is the prospect of global economic collapse: Hard times can divide us, or they can help us to understand each other better. In such fragmented times, finding the connections among us seems more urgent than ever. Travel-not sightseeing, but real encounters with real people-has never mattered more in helping us to see how we're crowding a blighted planet, how interdependent we are.

Just after Christmas in 2006, I saw a familiar face in a small hamburger restaurant near where I live on the North Shore of Oahu. Apparently unrecognized by anyone in the place, Senator Obama, in an aloha shirt, sat at a large table with his sister and about seven children, on a holiday outing. After they had finished eating, I introduced myself. The senator was tall, witty, charming, the soul of friendliness. He wanted to talk. No sooner had we exchanged pleasantries than I became engaged in a conversation unlike any I have had before or since in this little surfing town. "You know, like you, I've spent a lot of time in Southeast Asia. I lived in Indonesia," the senator said, as a way of introducing himself. We talked about Africa, about Cuba, about Hawaii. He wanted me to know that not only had he read my work but he had traveled and lived in distant lands, as well as in the poorer parts of America. In the conversation that followed, we talked about books, and life in general, but most of all we talked about the richness of the places we'd seen and how they had influenced us. Senator Obama seemed to define himself by the depth and complexity of his experience as a young man looking for his place in the wider world. With a glow of sympathy that was enlarged by humor and intelligence, he was utterly at home in the world. I mentioned that he'd make a great president and that he ought to run. He said he was studying it. That was the word he used. "But there's no hurry," I said, and making a play with his name in Swahili I added, "Haraka, haraka, haina baraka." He understood and laughed at this owlish jape ("Too much of a hurry makes bad luck"-or an unsuitable Barack, since his name and luck or blessing are synonymous). This in itself was an event: the only time in twenty years when anyone in my little town showed any knowledge of Swahili. Not long after that encounter, Obama gave a speech at Cornell College, in Iowa, calling on his audience and all Americans to go out and serve their community. "Growing up, I wasn't always sure who I was or where I was going," he said, describing how he got all sorts of advice, as young adults do, just before he became a community organizer in Chicago-when he decided, as he put it, "to step into the currents of history and help people fight for their dreams."

Obama's speech was a call to participate, to make a difference, to be more than a spectator in life. And since taking office, President Obama is once again calling on us to serve, to "engage" with the world. I don't immediately think of politicians as the greatest role models, but this man had his apprenticeship on the mean streets. His early foreign policy moves suggest a new way of looking at world conflicts. He has instructed George Mitchell, his special envoy to the Middle East, to go out and "listen."

This particular moment is remarkable-and different from the past eight or even sixteen years-because everyone on earth seems to be experiencing the same shrinking of net worth and an ensuing solemnity. But rather than retreating, many have chosen to look deeper into the possibilities that have arisen because of the global recession: Volunteerism is on the rise. Peace Corps applications jumped by 175 percent in the month of January over a year earlier. President Obama has pledged to boost Ameri-Corps and double the size of the Peace Corps. He is urging us to get to know our neighbors, here and in the world, and not to lecture or do battle but to listen and work.

The Peace Corps experience holds lessons for us all as travelers. As a teacher in Africa, I learned to listen. I discovered people with real lives and real problems, as well as dreams of transformation much like my own. From this distant place in Central Africa-colonial Nyasaland, soon to be independent Malawi-I saw America clearly, its virtues and its failings. Travel was revealed to me as an experience of being myself, in contact with people who had no preconceptions of who I was.

My decision to join the Peace Corps was an implicit rejection of sightseeing. Even then, tourists went to Africa as sensationalists and voyeurs. It was a novelty to be an American teacher in a little schoolhouse at the end of a narrow red clay road

in the bush. Whenever I mentioned Africa, people talked about Ernest Hemingway, and I laughed, thinking of him as strictly a bwana on safari, killing animals and talking to his gun bearers in what we called "kitchen Swahili." My hero then was not Hemingway, the rich visitor and fantasist, using the machismo of money, but Nelson Mandela, the committed individual, who'd just been given a sentence of life imprisonment on Robben Island for sabotage against South Africa's white regime, at the Rivonia trial.

I took pains to learn to speak the local Chichewa language grammatically. I never went on a safari, I did not own a camera, and most of the wild game I saw were the hyenas that raided my garbage pile, the bats that hung from the eaves of my house, and the occasional snake-black and green mambas-that rattled through the thicknesses of dead leaves on bush paths and in sun-heated maize fields. I stayed in Africa six years.

In Africa I had no material ambitions or hope of advancement. As an English teacher, I earned a stipend, just enough to support myself, but because it was so much more than anyone else in the country was earning I had nothing to complain about. It was only when I went into town and met, say, an American embassy official that I was reminded of my obscurity. Round about this time, the very youthful L. Paul Bremer, who was exactly my age but much more presentable, was shuffling paper at the U.S. embassy in Malawi as economic and commercial officer, earning a good salary and in the upward spiral of the diplomatic service. Later he would hold the exalted position of American proconsul in Iraq.

Around this same time, Chris Matthews was teaching in Swaziland, and Paul Tsongas, the late senator from Massachusetts, was a Peace Corps teacher in Ethiopia. When I met Tsongas much later, or bumped into other former Peace Corps volunteers (diplomats, businessmen, teachers, doctors), I found we had a great deal in common and had enjoyed many similar experiences, and felt an immediate bond. Most of all, I respected them for their years of service. None of them had had it easy, and some had had it very hard. An American consular official I recently met in India had spent two years in a tiny village in south central Zaire, in a mud hut, with no electricity, on a dead-end jungle road. The best years of his life, he said.

For the two years I was in Malawi, I never made a telephone call and my only contact with my family was in letters that took up to a month to arrive. This suited me fine. The instant connection in today's world tends to distort the experience of being far from home. What sort of a life is it when, on the days when things are going bad, you are able to dial Mom for consolation? The experience should involve remoteness, inconvenience, hardship, even risk; isn't that the whole point of being away? I don't understand a recent graduate doing a mediocre job, finding an apartment, getting into a routine in the hope of advancement. I do understand, with Huck Finn, the wish to light out for the territory ahead of the rest. I lived among people who, on the surface, seemed to have very little. Money was so scarce, they were practically existing on the barter system. The students' notebooks were always damp and penetrated by the odor of wood smoke from the cooking fires of their huts or the kerosene stink from the lamps: Electricity was rare in their villages. Though they wore a simple school uniform, my students were barefoot. Their soles were toughened by walking to school, and they played soccer barefoot. Before we developed a lunch program, lunch for most of them was a whole boiled potato or a few stalks of sugarcane that they chewed to stave off hunger. It would be easy, but misleading, to list all the things my students and their families didn't have. This is what celebrities do when they visit villages in Africa: Out of a guilty, grotesque, almost boasting self-consciousness, these wealthy visitors enumerate the insufficiencies. That's because they don't stay very long. If they stayed longer, perhaps a few years, they would see what I saw in Africa: the resiliency of the people. Africans knew neglect, drought, flood, bad harvests, hunger, disease, and-more insidious than any of these-tyrannical government; and yet in the face of these adversities they had developed survival skills, and prevailed. For more than forty years I've heard outsiders lamenting the plight of Africans-and, given AIDS and Darfur and Zimbabwe, sometimes justly; but I seldom hear, except from someone who has lived closely among them, how Africans, ignored by the world, have managed to save themselves, often in the bitterest of circumstances. My teaching had its uses for them, but what I taught was negligible compared to what I learned. Yes, after two years my students spoke and wrote English well, and some of them went on to college. But today, despite forty years of volunteer efforts, Malawi is probably worse off than it was back in 1963. The population has quadrupled to more than thirteen million (of these, one million are orphans), and the per capita income is $160 a year.

People talk about culture shock. I should have experienced it when I saw those mud huts or had my first case of malaria, or my surprising bout of myiasis-the putzi, or tumbu, fly eggs from my infested shirt hatching into maggots under my skin (I later turned this experience into a short story, "White Lies"). I learned to cope. I got culture shock when I came back to the United States. The country was pretty much the same-the Vietnam War was much hotter, more divisive, and destructive. But I was different.

I maintained links with my students and others in the country, and with my fellow Peace Corps teachers. Every summer we spend five days together: They are the best friends I have. I know many former volunteers who stay in touch with their village, or with friends, over many decades. The Malawi Children's Village, an orphanage, was started by former volunteers and has grown into a substantial project.

Like many people who have been affected by such an experience in a distant land, I did not come all the way home; nor did I leave that experience behind. It stayed in my mind, it informed my decisions, it made me strong. To all of this, there are people who will say, "What's the point?" But those are the same people who'll say what's the point of writing a poem, or learning a language, or going for a hike, or lingering on a wooded path to watch a bird flash onto a branch.

Whenever someone asks me what I think he should do with his life, I always say, First, leave home. Get out there, where if you care to listen, you will find many other people dreaming of making connections and changing the world, just like you. The only mistake is in thinking that you will make an important difference in the lives of the people you're among. The profound difference will be in you.