Part of the writing process for me of writing the book was, “What do I need to process about my—that’s connected to my own grief? And what is truly the story that I want to tell?” And I think even Peace Corps Volunteers wrestle with that. Like, “What do I need to process because it’s where my emotions are.” And so for me personally, I wanted to figure out how in the world she died. And so when I started writing, there was a lot of focus. I mean, I had to translate these tapes from Bambara and from French into English. And so that took a lot of time. And then I wrote a lot about the death. And I think I needed to do that from an emotional standpoint because that was so powerful. But as I wrote, I realized, “This book is not about her death; this is a book about her life.” And that’s when I really started to draw on my Peace Corps experience and the things that I experienced with her. And I think that’s hard for any Peace Corps writer, is trying to decide really what is the story because there are so many experiences and feelings that one can write about.

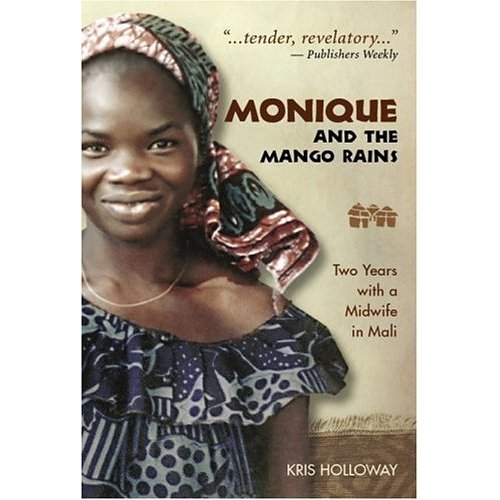

An Interview With Kris Holloway

Interview With Kris Holloway

Print this Page

* By Kris Holloway

* Country: Mali

* Dates of Service: 1989–1991

* Related Publication: Volunteer Voices

Amy Clark: I know that a lot of Peace Corps Volunteers write memoirs that are general about their experiences in their country, and very often those memoirs are written from the general viewpoint of cataloging the Peace Corps Volunteer’s experience there. In Monique and the Mango Rains, you take a different approach, and you tell someone else’s story. Can you tell us a little bit about what made you decide to write this particular story about Monique?

Kris Holloway: That's a great question. A lot of Peace Corps Volunteers write memoirs because it’s such a powerful experience. And for most people, it changed their lives in some way. There’s a before-Peace Corps experience and after-Peace Corps experience. And so, it makes sense that it generates writing because it generates powerful change and powerful feeling.

But for me, I think, as I said, I wasn’t really a writer. I mean, I did write when I was in Peace Corps. I wrote letters home to try to connect my family and the people that I loved—my friends and family—with what I was experiencing, so that they kept connected to me for those two years. But it wasn’t an internal process; it was more of an external. Like, “I want you to feel, and see, and smell what I’m seeing, and feeling, and smelling.” And that certainly helped me during my Peace Corps service feel less lonely and feel connected to my home. But I never felt like my Peace Corps experience was particularly different from other people’s so much.

The only thing that made it different was this outstanding woman that I became friends with. So I had always sort of thought, “Wow, I should really write a book about Monique Dimbele,” this midwife and healthcare worker who was sort of the first feminist in this part of rural Mali. And was saving women and children’s lives, was talking about female genital cutting, was talking about birth control, was working with women to keep their children healthy. And I was like, “Wow. I should really write about her.” But I didn’t; life is busy. I went to graduate school. I had kids. But when she died in childbirth as a midwife, my husband, who edited the book and who I met in Peace Corps. When we went back to Mali in 1999, you know, eight years after we had left, and I kept this tape recorder running talking with the midwives who attended Monique during that birth and her death. And I talked to her family members, and the village women, and the village chief. And I came home with these 16 hours of interview material. I said, “Oh, my gosh. People in Mali feel about Monique the same way I do. And if I don’t tell the world about who this woman was, no one will ever know her. No one will ever know that she’s not here anymore. Because half a million women die every year in childbirth, most of them in the developing world. So she could be seen as just a number. But she was my friend; she was this woman who changed the way I think about myself, and about women’s health, and about birth. So, my gosh, I want to let everybody know about her.”

So that was sort of the fire that I had within me to write this book. Part of the writing process for me of writing the book was, “What do I need to process about my—that’s connected to my own grief? And what is truly the story that I want to tell?” And I think even Peace Corps Volunteers wrestle with that. Like, “What do I need to process because it’s where my emotions are.”

And so for me personally, I wanted to figure out how in the world she died. And so when I started writing, there was a lot of focus. I mean, I had to translate these tapes from Bambara and from French into English. And so that took a lot of time. And then I wrote a lot about the death. And I think I needed to do that from an emotional standpoint because that was so powerful. But as I wrote, I realized, “This book is not about her death; this is a book about her life.” And that’s when I really started to draw on my Peace Corps experience and the things that I experienced with her. And I think that’s hard for any Peace Corps writer, is trying to decide really what is the story because there are so many experiences and feelings that one can write about.

Amy Clark: Can you tell us any more about your writing process and how you managed to so vividly capture some of those memories of living in Mali in words and on paper?

Kris Holloway: Well I think it was helpful that I did have those letters that I’d written home. Because they were—through those letters I really tried to explain to my family and friends what I was going through. So it wasn’t—like I said—a journal where I was just kind of processing my own experience, but it was really more trying to serve almost like a journalist and capture what life was like there. So that helped. Also, it so helped that I was married to my boyfriend that I met in Peace Corps. John, who had lived in my village with me for one year of his Peace Corps experience, so I could bounce things off of him, and say, “Well, do you remember this? And what was that like?” So he helped me fluff everything three dimensional.

And also, I had video of Monique here in the States, video that my parents and my sister had taken when they visited Mali when I was there. So I could see the mannerisms of Monique when she spoke, and I could see—I could hear the voices of people and the background sounds. So for me, it was almost like I had to immerse myself in a sensory experience because there’s nothing in my immediate world to remind me of this. So I would wake up at, you know, 5:00 a.m. in the morning because my kids were young and any parent can, you know, relate to the fact when the kids are awake and they’re young, you’re on. You know, there’s not a lot of down time. So I would put on, you know, Salif Keta or Umu Sangare or some music that brought Mali to life. I would smell mud cloth. Because in Mali there’s this rich, spicy scent to the air, and fabrics absorb it. So I would smell the, you know, the stuff I brought from Mali that I kept in a trunk so it retained some of its odor, and I would listen to Monique’s voice, and listen to the music, and kind of try to get myself back there and then write from that place.

Amy Clark: Can you just briefly tell us a little bit about your experience getting Monique published and what were some of the highs and lows of that publishing experience?

Kris Holloway: Briefly, huh? It took five years! So the first part was really getting the tapes translated. I also did a lot of research with anthropologists because I wanted to make sure that the story that I was telling of Monique actually illuminated some greater truths. There are not that many books written by or about African women. And so I knew that I wanted—I didn’t want to portray something that was so unique that it didn’t illuminate greater truth. And I thought it did, but I did a lot of research around social networks, and women’s health, and international development to make sure that I was getting at something deeper.

After that, I joined the national writer’s union to try to network with writers. Because it wasn’t my world; I didn’t know the first thing about writing and getting something published. And I knew I wanted to get something published. I wasn’t just going to write for my own mental health or my own pleasure; I wanted a book. And people thought I was pretty stupid, pretty naïve to think that I could just say, “I have to write a book and so I’m going to do it.” And, so I joined the national writer’s union. And I think I found out that I could write in scenes pretty well. I could write about 2,000 words and really describe a scene, but I realized I needed help creating a narrative flow. I mean, a book seemed really long. You know, wow, how in the world do you write, you know, 90,000 words? So I then realized I needed to work with fiction writers because they know how to do character development and tell a story. So I started taking fiction writing workshops. And they let me in! I was like, “I have to! This is a non-fiction book, but I need to learn from you.” And, you know, so that was really important in my development, these workshops, and then joining a manuscript critique group, where I had to turn in 25 pages every other week, or what have you.

So then I got this piece was published in World View magazine, and with that I got an agent. And then my agent tried to sell the book for about—I finished the manuscript with the great help of John, my husband. And she tried to sell the manuscript for a year and a half and couldn’t. You know, I still have all these rejection letters to remember that the “no” is always there—there’s always a “no”—and it just is one more step toward the yes. I think we get some of that patience and perseverance from our Peace Corps experience. Like, “Little road block, little road block, little road block, but, hey, you’re getting somewhere.” You know? Somewhere, something’s going to open up.

So finally, I got an academic publisher named Waveland Press, that said, “Yes” because they thought it would be really wonderful sort of as an ethnography, a personal ethnography, for the undergraduate market for women studies, for intro. to cultural anthropology, sociology, et cetera. But I still wanted it in the mainstream. I was like, “I want—I think everybody should read this. And we can all learn from this fabulous woman and the friendship I had with her.” So I had the great fortune of learning about a foundation called the Literary Ventures Fund. And they were started by a venture capitalist as a way to invest in books, and that they believe have the potential for changing the world. And they invested in Monique as their first nonfiction book.

Amy: Do you have any final words or pieces of advice for students who want to become writers, or Peace Corps Volunteers, or maybe even both?

Kris Holloway: Yes. I think the most important thing is if you want to write, write. I didn’t think I could write a book because it felt so big, you know? But then I knew I had to. And so if you have that feeling that comes from inside you like you have something to say, just keep writing. And don’t worry if it’s messy and ugly on the page. Don’t judge yourself by that. Just keep writing. Because you will get better. And form a group with other students who want to write. And there’s a lot of resources online for how to run critique groups. I’ve learned more giving good critique to other people’s work and receiving my own critique than through anything else. Because we all develop as writers; it’s not just a gift we’re given. It’s just something we have to work at. Just like anything: if you want to be a good runner, run. If you want to be a good singer, practice; you know, you sing all the time. So it’s nothing precious; it’s nothing magical. Just do it. So I think that’s huge for me. Just feel like you, for everyone to feel like they have a right to write, that they have a voice, and they need to use it.

I was angry at our society for somehow making people believe that you have to be a perfect speller or a perfect writer to write. And it’s just not true. The craft can come later; and though craft is important. So once you know that story, you sort of separated the wheat from the chaff. You know, really, what is it that you want to say? And then start learning craft. And I think the next thing is to get some small thing published. You know, it could be a student newspaper; it could be your local town newspaper. People want to hear young people’s voices. As I get older, I value the voices of young people more and more. And as a young person, I didn’t know that. I didn’t know how much older people wanted to hear me. I kind of thought they were just kind of—I don’t know—patting me on the back, “Oh, we want to hear you.” But it’s true because young people are the future, truly, and we want to hear about what their vision and what their stories are, and what they’re concerned about. So having that small piece published some place not only is important for other people to hear, but I think it also builds confidence in people as writers. “Oh, I got this piece published in my local paper. Well, maybe I could get something published in a larger paper or a magazine.” So these little concrete steps toward success, I think, could lead to something like a book.

Amy: Well, I wish you the best of luck. I hope it goes just as well for you as this has.

Kris Holloway: Thank you. Thanks, Amy.