2011.09.14: September 14, 2011: Ronald A. Schwarz writes: Kennedy's Orphans - The Story of Colombia 1

Peace Corps Online:

Directory:

Colombia:

Peace Corps Colombia :

Peace Corps Colombia: Newest Stories:

2011.09.14: September 14, 2011: Ronald A. Schwarz writes: Who are the First Volunteers? :

2011.09.14: September 14, 2011: Ronald A. Schwarz writes: Kennedy's Orphans - The Story of Colombia 1

- 2011.10.06: October 6, 2011: Malawi RPCV Gordon Radley tossed stones from Jerusalem over a muddy ridge in Colombia, scattered dirt from the family's cemetery plot, and recited the Jewish memorial prayer to keep a promise made 50 years earlier to honor the memory of his brother, Peace Corps Volunteer Larry Radley, who died in a plane crash there in 1962 Friday, October 07, 2011 - 11:52 pm [1]

- 2011.09.14: September 14, 2011: Peace Corps Interactive Timeline of first Peace Corps volunteers Friday, September 16, 2011 - 12:41 am [1]

Ronald A. Schwarz writes: Kennedy's Orphans - The Story of Colombia 1

"Kennedy's Orphans" is the story of Colombia One, the first group of Peace Corps Volunteers. They arrived at Rutgers University on June 25, 1961 and began training on the following day at 8:00 AM EDT. Two hours later a group bound for Tanganyika started training in El Paso, Texas. This happened less than four months after President Kennedy signed Executive Order 10924 that created the Peace Corps (March 1, 1961). The legislation that officially established the agency was passed by Congress and signed by the President on September 22, 1961 . . . two weeks after the first volunteers had arrived in Colombia. The following story is based on the experience of the author and the other 61 members of Colombia One. The content is drawn from draft chapters of a memoir - "Kennedy's Orphans" - that covers the volunteers' years in South America (1961-63) and their careers after President Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963.

Ronald A. Schwarz writes: Kennedy's Orphans - The Story of Colombia 1

Kennedy's Orphans

Ronald A. Schwarz

Minutes after midnight, September 7, 1961: Sixty-two men from all corners of America board a train at New York's Penn Station. Destination: the White House. We are Colombia One, the first Peace Corps Volunteers, on our way to meet our leader, El Presidente, John F. Kennedy. As dawn breaks, we arrive in Washington. In the morning hours we have a forgettable briefing at the State Department and a memorable photo-op session with Vice-President Lyndon Johnson.

In the late afternoon, we flash virgin passports to guards at the Pennsylvania Avenue gate and proceed to the White House. Richard Goodwin, one of Kennedy's Special Advisers, takes us on an insider tour through corridors connecting the offices of "the best and the brightest." He cautions, Athe meeting with the President is on hold.

Goodwin appears ill-at-ease. He had recently returned from meeting of hemisphere leaders in Uruguay where, in the early morning hours, he met a bearded, fatigue- outfitted diplomat: Che Guevara. Che conveyed his thanks the USA for the Bay of Pigs invasion noting that it "had been a great political victory for Cuba" and transformed them from an aggrieved little country to an equal. Che told Goodwin that "there is an intrinsic contradiction in the Alianza [Alliance for Progress] and that by encouraging the forces of change and the desires of the masses, the USA might set loose forces beyond its control that might end in more Cuban style revolutions in Latin America." [1]

Che's message may have been on Goodwin's mind as he guides us through the corridors of the Casa Blanca. A volunteer at his side explains our assignment to Colombia's national program of community development: "Our mission," he tells Goodwin, "is to encourage the forces of change and help the peasants take control of their own development." Unlike Guevara, we had given little thought to the revolutionary implications of our assignment.

Minutes after we enter the East Room, a buzzer sounds; the President is on his way. JFK, hand buried in his jacket pocket, descends the stairs and the rumble of conversation transforms into an electric silence. The President looks tired and distracted. At his side is his brother-in-law, the Peace Corps Director, Sargent Shriver. He reaches the floor of the East Room, is quickly surrounded by Volunteers and the campaign smile lights his face. Kennedy then speaks with passion of his hopes for the Peace Corps and the Alliance for Progress.

The President conveys his lack of confidence in the U.S. foreign policy establishment. It is not a new theme. During the 1960 election campaign against Richard Nixon, he criticized the "ill-chosen, ill-equipped, and ill-briefed ambassadors." JFK had read "The Ugly American" and wanted more Americans who, like the book's hero, worked at the grassroots and spoke the local language.

The President ends his briefing with, AI look forward to your return and want to hear what it's really like down there. He glances at Shriver and adds, AI don't know if this Peace Corps is going to work, but if you have any complaints don't write me, send them to Sarge.

A Profile of America's "Latest Weapon"

Caption: Members of Colombia I in a class on community development at Rutgers.

On paper, there is nothing exceptional about Colombia One. Almost half of us lack college degrees and one, Matt Deforest, a truck driver from Illinois, has only a high school diploma. In contrast to the degree-laden, Africa-bound teachers and engineers, we look and sound like what we are - a cross-section of young American men happy to gamble a few years overseas before the inevitable immersion into the challenges and comforts of adult life.

We report to Rutgers University on June 25, 1961. The training and two years of service begin at 8:00 AM on the following day. In the afternoon, we listen to Sargent Shriver's welcoming remarks and then plunge into countless meetings with reporters. The press captures our sense of humor and embryonic camaraderie, and dispels any notion that we are aspiring diplomats. The lead sentence in the Time Magazine article on the event reads,

Looking more like the freshman football team than America's latest weapon in the cold war, the first contingent of 80 Peace Corps volunteers sat in creaky wooden bleachers in the middle of the Rutgers University campus. [2]

We are young men with values shaped by World War II victories and post-war prosperity. For us, the Peace Corps is above all an adventure and secondly, an opportunity to help others. Only one member of the group views the assignment in

Our group includes a handful of Latinos: two with a Colombian heritage, one with Cuban parents and four of Mexican-American descent. Four were just 19, several were Army, Navy, Marine and Air Force veterans and two served in the Korean War. Geographically we covered a wide spectrum of states with the largest contingents coming from New York, California, Texas and Illinois. The training group includes one African-American and several Asian-Americans.

Caption: Members of Colombia I practice soccer in the Rutgers quadrangle.

A Diplomatic Arrival

The day after meeting with JFK, we board a chartered, propeller-driven, Avianca Super Constellation to Colombia. We land in Bogotá in the early morning under the cover of darkness. About a hundred people are on the tarmac to greet us. They include Colombian officials, U.S. Embassy representatives and CARE administrators. The largest contingent is from the Colombian military; soldiers dressed in combat uniforms and armed with automatic weapons.

Our spokesperson, a sleep-deprived Barney Hopewell tells the gathering that "We are ready to go to work to help the people of Colombia." The soldiers form a tight corridor from the plane, through customs, to the buses waiting to take us to Tibaitatá, a Rockefeller-funded agricultural research station - our home for the next five weeks.

The uniformed reception reflects caution, not ceremony. Colombia in 1961 is a wounded nation recovering from thirteen years of political violence that claimed more than 300,000 lives. Large areas of the country are prohibited zones for travel and volunteer placement. As young men, however, our optimism, naïveté and primitive faith in JFK's leadership inoculates us from anxiety and fear.

Colombians welcome us with warmth and enthusiasm due largely to the Kennedy charisma . . . and his Catholicism. We are ubiquitously referred to as Alos hijos de Kennedy B Kennedy's Children. We are hailed in the press . . . and misrepresented. A newspaper shows our pictures beneath a photograph of El Presidente Kennedy and identifies us as plumbers, carpenters, agronomists and, most frequently, as experts in "agricultural equipment."

On our first weekend in Bogotá, we meet the local elite, "los oligarchos." The project directors arranged for us to spend a weekend with Colombians who dominate the political institutions, own the huge farms and factories, run the universities and control the media. While they appear to support the aims of the Alliance for Progress, several agree with Che's analysis that it will ultimately undermine their power and privilege. One middle-aged woman hosting a volunteer in her mansion confesses that she "expects to be against the wall within a few years."

The following week we hear that our weekend with Colombia's upper class fueled a conflict at the Peace Corps' Washington Headquarters. The left-wingers on Shriver's staff viewed our warm-shower, gated-home hiatus as damaging to the agency's image. They wanted the world to see young, blue-jeaned Americans laying bricks for schools and working side by side with the peasants and Indians.

The first two weeks at Tibaitatá are filled with a succession of Ministerial visits and one by the President of Colombia, Alberto Lleras-Camargo. And, we have an audience with the Cardinal . . . downtown, at his quarters. As we extend our network of friends and acquaintances in Bogotá, we encounter university students, skeptics and critics on the left who see us as agents of Yankee imperialism and, for some, a branch of the CIA.

The Director of the Peace Corps in Colombia is Captain Chris Sheldon. Sheldon is wise, tough and attentive. In May 1961, four months before his arrival in Bogotá, his sailing school ship, the "Albatross," sank in a Caribbean storm. His wife and five students perished, and the tragedy is later immortalized in a book and a movie, AThe White Squall.

The Colombia One project is administered by CARE. The Director, Mert Cregger, is a licensed chiropractor who worked for a gold-mining company in Colombia before he joined CARE. Mert is a smart, indefatigable leader who earns our respect. CARE's activities in Colombia focus on food and tool distribution. Community development is in its portfolio, on paper.

The concept and practice of community development is new to the CARE/Peace Corps administration, and to the government of Colombia. Its Community Development Agency, Acción Comunal, has a short history, a new director and a small, poorly paid field staff. On a scorecard for "potential political disaster, the CARE-Peace Corps-Acción Comunal partnership earns an easy 10."

Getting Started

Caption: Members of Colombia I have five weeks of in-country training at Tibaitatá.

After five weeks of training at Tibaitatá, teams of two volunteers are dispatched to towns and villages throughout the country. The pairing is necessary because half of Colombia One still have difficulty advancing a conversation in Spanish beyond buenos dias and quiero una cerveza. By sending us in teams, the directors ensure that at least one of the Volunteers in a village can sustain a conversation.

My initial Peace Corps site is the small town of Santa Cruz, North of Bucaramanga. The setting is out of a Juan Valdez coffee commercial B green hills, cut by trails used by farmers and mules to transport sacks of sun-dried coffee beans to market. The town has 150 residents and is surrounded by family farms with a population of about 1,000. The stone-paved plaza has a Catholic church at a corner and a statue of the Virgin Mary at its center.

My partner, a fluent-in-Spanish Phil Lopes, and I settle into a spacious room in a house occupied by an extension agent of the Colombian Federation of Coffee Growers - Los Cafeteros. We paint walls, build furniture, buy horses and begin stage one of the community development process B meeting the locals and identifying their Afelt needs. This involves long walks on steep slippery trails, mounted visits to distant peasant farms, hundreds of cups of thick coffee, uncountable bottles of beer and endless conversations about President Kennedy. His status, in the minds of most Colombians, appear to be somewhere between the Pope and an outspoken Jewish carpenter.

In December 1961, a few months after we settle into our villages, JFK and his Spanish-speaking wife Jackie, arrive in Colombia. The Bogotá reception is tumultuous and the streets are packed with workers, peasants and shopkeepers. Looking out at the crowd from a window of the Presidential Palace, President Lleras offers JFK an explanation, AIt's because they believe you are on their side.

Kennedy's visit is widely covered on radio and in the press. It polishes the image of America, adds a notch or two to our status, and for the next eighteen months is featured in discussions in bars and general stores.

In our encounters with town dwellers and farmers (los campesinos) we preach the gospel of community development. The arrangement between CARE/Peace Corps and Acción Comunal calls for Volunteers to work with Colombian counterparts, promotores. In practice, some of us work closely with the promotores; others carve out their own niche and work separately.

Independently or together with counterparts, we inspire collective action to improve and build schools, roads and other infrastructure. Our main task is to organize community development committees (Juntas de Acción Comunal) in towns and in rural settlements (veredas).

The mobilization of villagers and the formation of committees generally go smoothly. The campesinos are attentive; they humor us and often go through the motions of a democratic vote. In fact, everyone except us knows who will run the juntas well before the scheduled Aelection.

Our weeks are filled with community meetings, manual labor, and travel to cities to secure technical assistance, financial aid and construction materials. We help farmers and townsfolk to repair and build roads, schools, health centers, playing fields, latrines and water supply systems. The major obstacles are the inevitable delays, our impatience, and our frustration with unfulfilled government promises of cement and bulldozers. Priests and local political bosses who try to hijack the Ademocratic process present another set of problems. Most, however, give us their support or bless us with indifference.

The Alliance for Progress also raises expectations of financial aid. We encounter officials and community leaders who see us as ambulatory checkbooks. In fact, we have no cash, materials or equipment. As "Kennedy's Children," however, we have access to Colombian authorities and feel no hesitation in requesting support from official agencies, the Coffee Federation and the private sector. CARE pitches in and provides sports equipment, picks and shovels and other tools.

The routine method of communication between the Peace Corps-CARE staff and the Volunteers is a mimeographed newsletter, the ALVOL. They outline monthly reporting requirements, guidance on how to purchase a horse (Athe returnable property of CARE) and information on conferences, life insurance and health tips. ALVOL 51 (July 16, 1962) notes, ANew snake bite serum will be issued to each volunteer. If you have old snake bite serum, please discard it on receipt of the new supply. Reminders to boil water and use condoms are favorite topics, and are largely ignored.

Communication between volunteers and staff is slow and technologically primitive. Some towns have telephones, but it takes a day or two, and luck, to complete a call. The Bogotá-based administrators contact us via a telegram that usually arrives within two or three days. The infrequent and limited contact with our directors is a blessing. It gives us time to make mistakes, and either correct them, or move on to something else.

For a group of youthful American males, Colombia provides countless opportunities for distraction. The sounds of salsa in buses, bars and boutiques are relentless. The beer costs eight cents a bottle and the women are beautiful. Most months a city holds a three to five day carnival, often with bullfights and the best matadors from Spain, Mexico and Colombia. All feature large cumbia and pachanga orchestras who play until dawn under mammoth tents. At the fiestas, we make our cultural contribution to Colombia B demonstrations of how to do "The Twist."

Air transport is cheap, and by staying in our villages for three consecutive weeks we "earn a week of leisure." A handful of volunteers cash in with astonishing regularity and the Cuerpos de Paz [the Peace Corps] achieves notoriety as los Cuerpos de Paseo - the vacation corps.

The Peace Corps administration contributes to our rounds of recreation by holding periodic conferences. It is their way to learn what we are doing, how the program could be improved, and our psychological condition. For the group of young, university-based psychologists who test us with relentless regularity, we are stepping stones to tenure.

One conference timed to remove us from possible violence during national elections in 1962, takes place in the cities of Santa Marta and Cartagena on the Caribbean coast. The venue for the Santa Marta conference is the Aguila beer factory. During breaks we have the option of coffee or a cold brew. Meetings last until midday, and afternoons feature water skiing and touch football at the beach. Evenings are devoted to diners at seaside cafés, endless rounds of poker and excursions to local brothels.

One nighttime adventure shared by a dozen volunteers features a private bus to the brothel Las Americas, hours of debauchery, a drunken brawl, police sirens and a high speed chase through the streets of Santa Marta. We escape capture and the incident is not picked up by the local press.

The First Peace Corps Fatalities

The month following the coastal conference, tragedy strikes. A handful of volunteers hustle airplane seats after spending their Easter vacation in the Chocó - a vast jungle region bordering the Pacific coast. The first plane out, an AVISPA DC-3, is over- booked and has room for only two volunteers. David Crozier and Larry Radley get on board. A few hours after takeoff the plane is reported missing and a search is quickly organized. The Colombian government and the U.S. Army send planes and helicopters but find no trace of the aircraft. A few days later the wreckage is spotted near the top of a steep mountain ridge. The tropical vegetation is dense; it is impossible to land the chopper, and a descent by cable is too risky. An attempt to reach the site on foot also fails.

On April 29th, a week after the plane was reported lost, a team of five men led by a Colombian Air Force officer and a U.S. Army Captain make a hazardous descent by cable from a helicopter hovering over the crash site. They build a landing pad and are joined by three Colombia One Volunteers, Ned Chalker, Steve Honore and Barney Hopewell. Ned's report of the scene reads, Athe people were unrecognizable, there were no whole bodies. Heads and arms and other pieces much too terrible to describe were lying around. The Peace Corps has its first fatalities.

Chalker, Honore and Hopewell confirm the identity of the dead Volunteers by their Sears boots. An official ceremony is held and the ground is sanctioned as a cemetery. Before departing, the rescue team constructs several wooden crosses. The remains of all passengers and crew are still at rest on the mountainside.

Following the death of their son, the Croziers' hand Sargent Shriver, a copy of a letter they received from David. The last line reads: "Should it come to it, I would rather give my life trying to help someone than to have to give my life looking down the barrel of a gun at them."

Shriver hangs a framed copy of the letter on his office wall. The Peace Corps acknowledges David and Larry's sacrifice by naming two training sites in Puerto Rico after them: Camp Crozier and Camp Radley.

The Second Year

The following year is far different from the first. Most of us are now separated from our original partners. New sites are opened and a handful of new Volunteers partner with members of Colombia One. Culture shock fades, our Spanish improves and we adapt to the Colombian way of doing things. Our towns and villages are now homes rather than places to escape from.

I leave my new partner, a Colombia II Volunteer, behind in Santa Cruz and begin year two with a vacation that takes me to Peru and Chile. I arrive in Lima the day after a coup d'état and stop at the Peace Corps headquarters to chat with Frank Mankiewicz, the country director. We look out his office window and watch tanks and soldiers patrolling the streets. Frank turns, looks me in the eye and says "Next time the Indians will be in those tanks." Che, it appears, is not without friends in the Kennedy administration.

I proceed to Chile for a week of skiing and a week of wine tasting. On my return to Colombia I learn that the Departmental (State) Director of Acción Comunal, a bureaucrat who never set foot in Santa Cruz, had inaugurated "his projects" – the two aqueducts built by juntas I organized. I confront the S.O.B. in his office and exit shouting epithets that I feared would get me expelled from Colombia.

A few days later a telegram from Chris Sheldon arrives in Santa Cruz. The message: "Your travel to Bogotá is authorized. Report ASAP." A few days later we meet, he suggests a transfer and the following month I arrive in a new site, Silvia, Cauca, about 1,000 kilometers southwest of Santa Cruz.

My partner in Silvia is the taciturn, mustached Al Wahrhaftig, one of the few scholars in Colombia One. Al did the leg work to open the site and we become part of a team with the Colombian Division of Indian Affairs and a United Nations program. Al has a master's degree in anthropology and skillfully adapts the philosophy and rules of Acción Comunal to the traditional leadership structure of the indigenous reservation communities we work with.

My monthly schedule includes 40 to 60 hours traveling alone on foot and horseback to remote villages, 12 to 15 nights sleeping on a bench or table, endless meetings with reservation leaders, dozens of days working on construction projects, and a visit to the State Capitol to discuss plans or request materials from government officials. Weekend activities include work on a school or road project in Silvia, soccer practice, league games, and dancing and drinking at a local bar. The pattern, with uncountable variations, is shared by the other members of Colombia One.

Community Development in El Chilcal

Darrel Young, Rick Jaspersen and Aurelio (their Colombian counterpart) hold their first big junta meeting in the rural settlement of Chilcal (pop. 200), in the Department of Nariño. The venue is a school that was designed, built and donated to the village by the Cafeteros. At the school, the residents agree on their first community development project - an aqueduct to bring potable water to Chilcal.

The following months are filled with dust-filled bus trips and meetings to obtain funds and technical support. Acción Comunal cuts a modest check and the Cafeteros contribute tubes, bricks, cement and the services of an engineer. The Chilcal residents supply the sand, gravel and labor. It takes almost a year to construct and community members contribute thousands of work days. In his account of the inauguration, Darrel notes,

It's a historic moment. People have changed. They look the same, but they carry themselves differently; shoulders are squarer, heads are higher and their voices are stronger, more confident . . . more hopeful.

A few weeks later, the Cafeteros change their policy and end their support for community development. The official reason is financial, but through Aurelio, Darrel learns the real reason:

The big bosses in Nariño's Cafetero headquarters became suspicious of Acción Comunal. They viewed the new assertive attitude and sense of self-confidence as threatening. The Cafeteros didn't withdraw support but wanted to deliver it in the traditional manner - top down, without local participation. They want their largess to be met with lowered eyes, deference and gratitude.

With a new volunteer partner but without help from the Cafeteros, Darrel continues to apply the community development approach in other settlements. Villagers hold festivals to raise cash and CARE donates a Cinva Ram machine. The residents make bricks and use them to build schools and clinics. Darrel's comment on his two years: "I joined the Peace Corps to save the world, and when I left saving the world seemed very doable."

Colombia One's Contribution

The variety and number of projects started and finished by Colombia One volunteers is far greater than anyone, including ourselves, would have predicted. The official report of completed projects includes 44 schools, 65 classrooms, 29 rural roads (200 miles), 27 aqueducts, four health centers, 26 cooperatives, 100 sports fields, several hundred latrines and the formation of hundreds of community development committees. An even greater number of projects are listed as Ain progress. Some figures reveal traces of statistical sorcery.

We get more credit than we deserve; "our projects" are mostly managed and completed by campesinos, our counterparts and local leaders. Our most important contribution is just being there, listening, and trying to get something done. As Americans working in rural villages, we brought attention and publicity to Acción Comunal.

Observers within and outside the Peace Corps administration agree that the Colombia One program exceeded expectations. David Hapgood and Meridan Bennett, two ex- Peace Corps staff, note in their book that "Without Peace Corps help, Acción Comunal might have disappeared in 1962, when it was still shaky, insecure and overextended." The Peace Corps Historian, Gerard Rice, writing about the program states that Ait was a significant success.

Another author comments that "Members of this first Colombia group . . . wrote in action the basic Peace Corps textbook on community development." These and similar comments suggest that the Volunteers of Colombia One helped transform a stumbling Colombian bureaucracy into a national development organization, one that still exists.

What Ever Happened to Colombia One

Fifty years have passed since our arrival in Colombia. In spite of being scattered throughout the USA and the world, we keep in touch. It began with a newsletter in 1965 and continues today via the internet. We visit each others' homes and meet periodically in small groups throughout America. Every five years, usually in conjunction with a national Peace Corps event, 20 to 30 of us get together for Colombia One parties hosted by Moon Mullins and Ned Chalker.

As part of the initial wave of returned volunteers in the early >60's, members of Colombia One played a role in Peace Corps management, recruitment and training. Several held positions in Washington, others were Peace Corps staff in Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Honduras, Peru, Turkey and the Philippines. Four served as Country Directors. Many others taught in training programs and helped prepare more than 5,000 volunteers for Peace Corps service, mostly for assignments in Latin America.

In 2003, after the death of Jim Puccetti, a Volunteer Leader and one of several in our group to marry a Colombian, I began an odyssey to investigate what happened to Colombia One. It involved frequent travel between my home in France to their homes in the USA and to archives in Boston, New York and Washington. What surprised me was how little my fellow volunteers had changed. All claimed the Peace Corps experience was one of the most important events in their lives. Their stories confirm this.

A Korean War veteran and modern Renaissance man, Bill Woudenberg, lives in a small apartment in Weehawken, New Jersey. He works part time as an architectural draftsman, his profession at the time he joined the Peace Corps. "Woody" is also an award-winning artist.

In Colombia, Woody invented a loom to weave bamboo for use in latrine construction. Years later, working for an international NGO, he applied the technique to the manufacture of reinforced concrete products used in grain and cold storage containers. Factories using the technology were built in Bangladesh and Togo and employed several hundred workers.

The technology, under his supervision, was also applied in the construction of an international airport and the national museum in Bangladesh. Reflecting on his experience, Bill tells me, A In the Peace Corps I learned I could survive. I never worried about a career. . . . I'm probably the poorest guy in Colombia One, but I've had a good life, no regrets."

Henry Jibaja, born in the USA to Cuban parents is one of the few Colombia One volunteers with a degree in agriculture. Looking back on his Peace Corps days, Henry recalls, Awe get to Colombia and they send me to Buenaventura, 26 feet of rain per year, one of the few places in the country where there is no agriculture.

In 1972, Sargent Shriver hired Henry to organize the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEC) headquarters in Florida. Henry played the key role in setting up VISTA in Florida and for 20 years was Director of the statewide volunteer coordination agency. He had opportunities for higher positions but that meant moving to Washington. Henry chose to stay in Florida to work with volunteers. He has no taste for tenured bureaucrats or political appointees: ADealing with them is awful."

In Tucson, I spend a few days with my first partner, the "Honorable" Phil Lopes. After the Peace Corps, Phil finished college and completed a masters degree in anthropology. He returned to the Peace Corps and served as Country Director in Ecuador and Co-Director in Brazil. The other Co-Director in Brazil, his wife Pam, is also a Returned Volunteer. In Arizona, Phil led the effort to establish Pima Community College, and the University of Arizona College of Public Health. He is now the minority leader in the Republican dominated Arizona House of Representatives and spearheads the effort to reform the state health care system.

Sitting in his living room in 2005, I ask Phil what he had accomplished recently. He hands me Section B of the Arizona Daily Star. The headline reads, "Pascua Yaquis get housing boost." The article outlines a new state law that gives a property tax exemption to off-reservation homes owned by low-income tribal members. Phil Lopes is listed as the primary sponsor. I offer congratulations but Phil interrupts, "Those Yaquis, they have good lobbyists. I wouldn't have been able to get it through the House without those lobbyists. I don't have the guns."

John Arango, whose father was born and raised in Antioquia, Colombia, spent his early post-Peace Corps years as Director of the Peace Corps Community Development Training Center at the University of New Mexico. He later served as Peace Corps Director in Ecuador and Panama (under Ambassador Jack Vaughn, the Peace Corp's second Director). A picture on a wall of his New Mexico home shows his wife Polly receiving an award from President Clinton for her work with disabled children.

In a long career as head of Algodones Associates, John focused on obtaining rights for illegal immigrants' access to education. He also played a part in the American Bar Association's successful struggle to obtain mandatory funding for legal services for the indigent. The case was successfully argued before the Supreme Court. John is now Director of New Mexico Legal Aid, a state-wide, non-profit organization with 12 offices that employs 35 lawyers.

Seated on his veranda, John tells me about a national meeting of lawyers he recently attended in Washington; "It dealt with defending the rights of the poor . . . and every one of us was a former Peace Corps Volunteer.

More than half of Colombia One spent some or all of their careers in international development and humanitarian activities. Collectively, they worked in more than 100 countries with the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank, the UN, the European Union, USAID, USIA, CARE, the Red Cross, and other public and private agencies. They initiated and participated in the establishment of low cost housing programs in Central America, rural electrification, small industry development in Nigeria, rural service centers in the Philippines, the reform of Kenya's health sector, disaster relief programs in Latin America, and a Famine Early Warning System for Sub-Sahara Africa.

As economists, administrators and consultants they designed and managed hundreds of projects and loan portfolios in and for developing countries. Rick Jaspersen held senior positions in the World Bank and the Inter American Development Bank, and is currently Director of the Latin American Department at the Institute of International Finance. Dennis Grubb directed projects to set up stock markets in India, Sri Lanka and Mongolia. Lyle Smith served as Director of Programs for Project Hope in China and established the first pediatric hospital in Shanghai. Bruce Lane, often working with Al Wahrhaftig, produced films on Mexico and Afghanistan and is currently putting together a documentary on Colombia One.

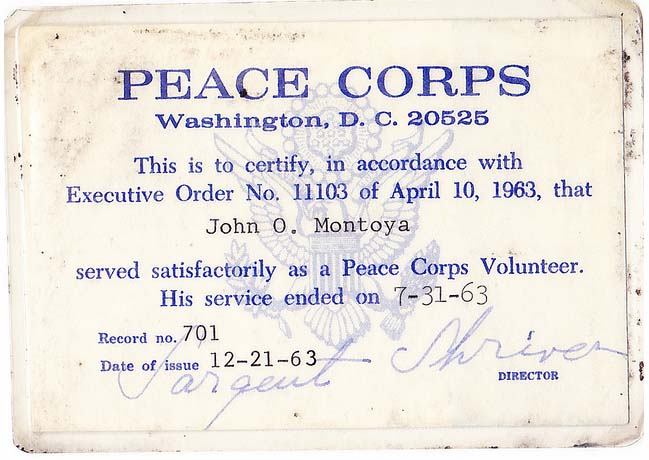

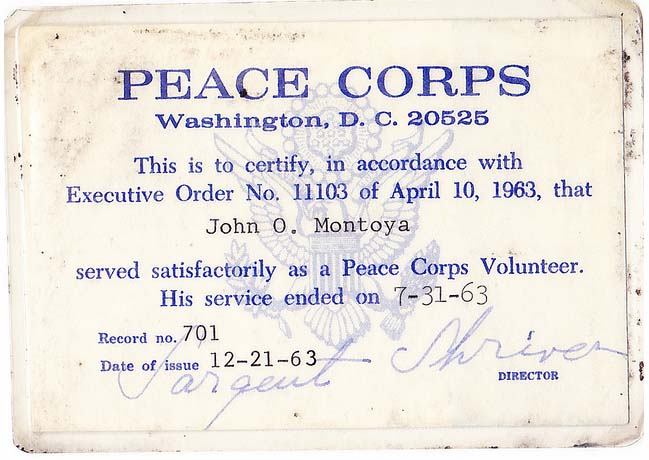

In the USA, Returned Colombia One Volunteers are leaders in education, public health, public service and in the private sector. Tom Torres worked with Model Cities, Head Start and served as Director for the Administration of Native American Programs for Hawaii and the Outer Pacific Islands. John Montoya was an Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) officer and was recognized with an achievement award for his efforts in fighting discrimination and poverty. Mike Lanigan managed disaster relief activities for the Red Cross in the USA, Puerto Rico and Peru. Tom Bentley and his ex-volunteer wife Elizabeth helped create the Indochinese Cultural and Service Center in Oregon.

The confirmed conservatives in Colombia One put their principles into practice in the private sector. John Luoma invented and manufactured a mini fork lift for use on construction sites. His latest venture is a commercial reforestation project and the production of chilies and papayas on his farm in the Yucatan. Buck Perry and his wife Evelyn (a Volunteer in Colombia III) are settled in South Carolina and manage their own electronic services business. Mike Willson worked for KFC and Brown & Williamson Tobacco as an advertising executive. Others with more moderate political leanings had jobs in real estate, construction, horticulture, information technology, education, law enforcement and government at local, state and national levels.

Steve Honore served as Peace Corps Director in the Dominican Republic (1978-81), and in 2000, received the Peace Corps' Franklin Williams Award for Outstanding Community Service. More than a half dozen including Jack Elzinga, George Kroon, Darrel Young, Bruce Richardson, Steve Honore and Al Wahrhaftig were professors at U.S. universities. Most members of Colombia One continue volunteer activities in their communities. Two, Michael Murray and Ned Chalker, spearhead major urban development projects, pro bono.

After his retirement as president of a large manufacturing company, Stewart-Warner, Michael Murray dedicated himself to public service in St. Louis. He was a founding board member for the $100 million reconstruction of Forest Park. The park is larger than New York's Central Park and includes a golf course, facilities for boating, tennis and ice skating, a zoo, a planetarium and two museums.

Murray is now President of the Board of the Metropolitan Park and Recreation District, a.k.a. The Great Rivers Greenway District. It features a connected series of greenways, parks and trails that cross state lines and will eventually encircle the St. Louis region. Commenting on his experience, Murray notes, ADeTocqueville had it exactly right when he observed how important citizen involvement is to our democracy.

Ned Chalker retired from the National Institute of Education (NIE), and in 2000 founded the National Maritime Heritage Foundation (NMHF). The Foundation is a partner with the District of Columbia and the Navy Department in the effort to build a national capitol tall ship, the Spirit of Enterprise, and a create a Washington Maritime Center. The projects are part of an urban redevelopment program for Southwest Washington. The NMHF also plans Ned, who grew up in the small town of Chester, Connecticut, summed up his Peace Corps experience in Antioquia: AI met all these people who after you got to know them were just like the people I grew up with . . . except they spoke Spanish.

While interviewing Ned in 2004, he hands me a printout from a blog site, Pharyngula. The author of the post is Ed Darrell, a George Bush Sr. political appointee and Ned's boss at the NIE in the 1980s. It reads:

I had a wonderful ‘program manager' named Ned Chalker – the guy who got things done. He was one of the original Peace Corps volunteers, and many in his network were the early recruits. They could all do anything, including make the government run well and cheaply -- and they were all waiting in second and third-tier civil service jobs for someone, like a John Kennedy, to come back to power and ask them to . . . make their nation good, grand and proud.

Kennedy's name and his vision of a democratic and socially responsible society continue to inflame political debate throughout the Americas. Of all JFK's initiatives, the one that most clearly carries his message is the Peace Corps. And, in the words of his biographer Robert Dallek, the Peace Corps remains "one of the enduring legacies of Kennedy's Presidency."

The Torch Keeps Burning

In September 2006, 22 members of Colombia One gather in Washington for the 45th anniversary of the Peace Corps celebration. The opening dinner is at a Colombian restaurant in Northern Virginia. Most show up in the latest Colombia One sport shirt, courtesy of Mike Willson. The logo on the chest reads "Colombia I – Numero Uno – y no lo olvides" (Colombia I – Number One - and don't you forget it).

The right sleeve has two embroidered flags – one, the stars and stripes of the USA, and another, the horizontal bands of yellow, red and blue; the colors of the flag of Colombia. A waiter leads Willson to the group table, looks at the sleeve and remarks, "You've got it wrong, the blue stripe belongs in the middle."

The following evening Returned Volunteers who served in Colombia attend a reception at the elegant residence of the newly appointed Colombian Ambassador to the USA, Carolina Barco-Isakson. Her welcoming remarks include a request to continue and expand people-to-people projects in Colombia. In private conversations with Colombian diplomats, two other topics are discussed – a Caribbean coast reunion for Colombian RPCVs and the return of the Peace Corps to Colombia.

Two years later, in February 2008, thirteen members of Colombia One participate in a four-day conference in Cartagena; 184 Returned Colombia Volunteers are present.

The conference, "Reconnecting with Colombia" is jointly organized by the Friends of Colombia (FOC) and the Colombian Embassy. California Congressman Sam Farr and Vanity Fair correspondent Maureen Orth are there; both were volunteers in Colombia in the mid-1960s. The reunion coincides with anti-FARC demonstrations staged in cities throughout the world.

We listen to speeches and discuss events and with Colombia's President Alvaro Uribe, Ministers, the U.S. Ambassador to Colombia, and Ambassador Barco. President Uribe announces that the FOC will receive La Cruz de la Orden Nacional al Mérito (The Silver Cross of the National Order of Merit). The award is presented to Arleen Cheston, President of the FOC, by the young woman who organized the anti- FARC demonstration in Cartagena.

The highlight of the four days is a party that features a live salsa orchestra and on the deck of the four-mast, 23 sail flagship of the Colombia Navy, "The Gloria." Discussions on ways of reconnecting with Colombia accelerate.

In February 2009, President Alvaro Uribe writes to Jody Olsen, Acting Director of the Peace Corps. The letter ends with: "We are honored to formally invite the Peace Corps to return to Colombia. We know what a valuable contribution the Peace Corps makes to both of our countries." In September 2010, after an absence of 30 years, Peace Corps Volunteers once again arrive in Colombia.

Rutgers (and NBC TV) Celebrate the First Volunteers

JUNE 2010: Anxious to celebrate our 50th Anniversary before we all pass the seven decade milestone, a handful of Colombia One volunteers initiate discussions with Rutgers University for a November reunion. The effort is spearheaded by John Montoya, Martin Acevedo and Buck Northrop; Darrel Young designs a plaque based on the logo he created for the 2006 Colombia One T- shirt.

On November 4th and 5th, thirty-four members of Colombia One are guests at the New Brunswick Marriot. Most are accompanied by wives and several come with their children. Rutgers University flawlessly manages the media and logistics. The first day includes lunch, speeches and interviews with the press and TV reporters. A team from NBC News records the happenings and conduct interviews. The following evening the story is broadcast nationally on the Brian Williams TV news segment, "Making a Difference."

The main event, the unveiling of the plaque, takes place on November 5th under a tent set up in the quad formed by the dormitories we occupied in the summer of 1961. It is a chilly and windy morning. The ceremony includes speeches by representatives from the Peace Corps, the Colombian Federation of Coffee-Growers, CARE and Rutgers University. Members of Colombia One offer inspirational anecdotes and war stories that resemble tribal legends.

The ceremony ends with the unveiling of a huge brass plaque next to the entrance to a dormitory. It is a replica of the flag of the USA with stripes formed by the last names of the 62 volunteers; Acevedo, Adcock . . . Yaeger, Young. The final paragraphs read:

This plaque commemorates those first volunteers; their enthusiasm, work ethic [and] deep commitment . . . captured the imagination of Americans and Colombians alike and set an example for generations to come.

It also honors the legacy of President John F. Kennedy, whose call in his inaugural address of 1961 they so eagerly heeded:

". . . ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country."

It is almost 50 years since we met with El Presidente in the White House. While he presided, we and a few thousand other Volunteers were lucky to serve in Latin America as Kennedy's Children. The experience opened our eyes to a new world of challenges and the opportunity to discover that life's greatest reward comes from trying to make it better for others.

Our service in the Peace Corps was the beginning. In our careers and personal lives we – as Kennedy's Orphans – helped transform JFK's vision into a legacy that continues to be harvested.

Footnotes:

[1} The Che Guevara remarks to Goodwin are a reconstruction of statements in Goodwin's notes

of the meeting.

[2} Time Magazine (July 10, 1961).}

APPENDIX: Colombia One Peace Corps Volunteers*

Martin ACEVEDO, Jr.

Howard Terry ADCOCK

Charles R. AKIN

John Brownell ARANGO

Ronald Conway ATWATER

Thomas Weinheimer BENTLEY

Ned CHALKER

David Leonard CROZIER

Richard James DANCEY

Matthew M. DeFOREST

Davey Edmund DOWNING

D. Jack ELZINGA

Alexander I. ESTRIN

Richard D. FIEDLER

Terrence T. GRANT

James Edward GREGORY

Ira E. GWIN

Dennis GRUBB

Neil Louis HANSEN

Ray Cloyne HASELBY

Stephan LeRoy HONORE

Byron T. HOPEWELL

Fred Z. JASPERSEN

Henry Joseph JIBAJA

Thomas J. KENWORTHY

George E. KROON

John W. KUHNS

Richard L. KUNZ

Bruce Elliott LANE

Michael A. LANIGAN

Albert William LEWIS, Jr.

John J. LEWIS

Phillip M. LOPES

John Frank LUOMA

Frederick Y. McCLUSKY

Gerald P. McMAHON

John Orlando MONTOYA

Enrique MORALES

James Thomas MULLINS, Jr.

Stephen Michael MURRAY

Harold Riley NORTHRUP

Kent OLDENBURG

Charles G. PERRY, III

James J. PUCCETTI

Lawrence M. RADLEY

Henry Bruce RAYMOND

Bruce D. RICHARDSON

Dennis M. SALGADO

Ronald Allan SCHWARZ

Lyle Leon SMITH

Emil Gustave STEINKRAUSS

James M. TENAGLIA

Tomas Rumaldo TORRES

Albert L. WAHRHAFTIG

James Roy WELCOME

Daniel Martin WEMHOFF

Thomas Charles WHALEN

Bradford Humes WHIPPLE

Michael Owen WILLSON

William Frederick WOUDENBERG

Roland Newell YAEGER

Darrel Allen YOUNG

*Al FERRARO trained with Colombia One and arrived in Colombia in 1962.

About the Author

Ronald A. Schwarz is an anthropologist who grew up in Brooklyn, New York. He was selected for the Peace Corps after graduation from Colgate University. Following his years in Colombia, he completed a doctorate in anthropology at Michigan State University and trained Volunteers for programs in Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Venezuela. He then returned to Colombia where he established and directed an anthropology field training program and a wooden toy factory.

Dr. Schwarz was a faculty member at Williams College, Colgate University, Tulane University and the Johns Hopkins University. Between 1990 and 2002, he was the Director of Development Solutions for Africa, based in Nairobi, Kenya. He is the co- editor of three books on anthropology and the principal investigator of research and planning documents for the World Bank, USAID, the U.N., the European Union and the bilateral development agencies of Denmark, Sweden, Germany, Japan and the United Kingdom.

About the Book

KENNEDY'S ORPHANS is the story of Colombia One, the first group of Peace Corps Volunteers. They arrived at Rutgers University on June 25, 1961 and began training on the following day at 8:00 AM EDT. Two hours later a group bound for Tanganyika started training in El Paso, Texas. This happened less than four months after President Kennedy signed Executive Order 10924 that created the Peace Corps (March 1, 1961). The legislation that officially established the agency was passed by Congress and signed by the President on September 22, 1961 . . . two weeks after the first volunteers had arrived in Colombia.

The following story is based on the experience of the author and the other 61 members of Colombia One. The content is drawn from draft chapters of a memoir - "KENNEDY'S ORPHANS" - that covers the volunteers' years in South America (1961-63) and their careers after President Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963.

An earlier version of this story appears as a chapter in "GATHER FRUIT ONE BY ONE" edited by Pat and Bernie Alter and published in 2011 by Travelers' Tales and Solas House. It is one of four volumes of Peace Corps stories edited by Jane Albritton.

Links to Related Topics (Tags):

Headlines: September, 2011; Peace Corps Colombia; Directory of Colombia RPCVs; Messages and Announcements for Colombia RPCVs; 50th Anniversary of the Peace Corps

When this story was posted in September 2011, this was on the front page of PCOL:

Peace Corps Online The Independent News Forum serving Returned Peace Corps Volunteers

| DC you in September

Come to Washington DC to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Peace Corps from September 21 to 25. There will be an open house at Peace Corps Headquarters, advocacy training, a service day, a staff reunion that all living directors will attend, Peace Corps Night with the Washington Nationals, the Peace Corps Gala, Third Goal Bash, a memorial to fallen Peace Corps Volunteers at Arlington Cemetery, the 50th Anniversary Walk of Flags and the NPCA's Peace Festival. Here's the schedule of events. |

| Peace Corps Featured at Smithsonian

Take a look at our photo essay of Peace Corps' featured program at the 2011 Smithsonian Folklife Festival on the National Mall in Washington DC to see how the festival showcased the work of Peace Corps volunteers in economic development and income generation; ways volunteers have helped support local groups to help educate communities; and food and cooking traditions that have played a role in the Peace Corps experience. New: Enjoy photos from the second week of the exposition. |

| Peace Corps: The Next Fifty Years

As we move into the Peace Corps' second fifty years, what single improvement would most benefit the mission of the Peace Corps? Read our op-ed about the creation of a private charitable non-profit corporation, independent of the US government, whose focus would be to provide support and funding for third goal activities. Returned Volunteers need President Obama to support the enabling legislation, already written and vetted, to create the Peace Corps Foundation. RPCVs will do the rest. |

| How Volunteers Remember Sarge

As the Peace Corps' Founding Director Sargent Shriver laid the foundations for the most lasting accomplishment of the Kennedy presidency. Shriver spoke to returned volunteers at the Peace Vigil at Lincoln Memorial in September, 2001 for the Peace Corps 40th. "The challenge I believe is simple - simple to express but difficult to fulfill. That challenge is expressed in these words: PCV's - stay as you are. Be servants of peace. Work at home as you have worked abroad. Humbly, persistently, intelligently. Weep with those who are sorrowful, Care for those who are sick. Serve your wives, serve your husbands, serve your families, serve your neighbors, serve your cities, serve the poor, join others who also serve," said Shriver. "Serve, Serve, Serve. That's the answer, that's the objective, that's the challenge." |

Read the stories and leave your comments.

Some postings on Peace Corps Online are provided to the individual members of this group without permission of the copyright owner for the non-profit purposes of criticism, comment, education, scholarship, and research under the "Fair Use" provisions of U.S. Government copyright laws and they may not be distributed further without permission of the copyright owner. Peace Corps Online does not vouch for the accuracy of the content of the postings, which is the sole responsibility of the copyright holder.

Story Source: PCOL Exclusive

This story has been posted in the following forums: : Headlines; COS - Colombia; 50th

PCOL47299

71

My best friend Raymond Wood served in the Peace Corp in the late 1960s and I need information about his service for a biography I am writing about hm. Please contact me at 314 308 7075 4944 Lindell 7w, st. louis mo 63108:

RAYMOND WOOD, HEADED NASH CENTER

Published August 3, 1995

Funeral services for the Rev. Raymond W. Wood, 50, a civil rights activist and the first director of the Jesse E. Nash Health Center in 1973, will be held at 7 p.m. today in St. John Baptist Church, 184 Goodell St.Burial will be at 10 a.m. Saturday in Ridge Lawn Cemetery, Cheektowaga.Mr. Wood died Saturday (July 29, 1995) at his home in Tampa, Fla., after a short illness.Born in Rochester, he came to Buffalo with his family as a child. He was valedictorian of his class at Lafayette High School, attended Elmhurst College and earned master's degrees in divinity, social work, public health and public administration. He received his doctorate in public administration from the University of Southern California. In the 1960s, he served as a Peace Corps volunteer in the Philippines and took part in the historic civil rights marches in Selma, Ala., and Washington, D.C., with the Ministers' Alliance.In addition to his post at the Jesse Nash Center, he was executive director of Hunter Health Plan Inc. in Lexington, Ky., and associate administrator of the D.C. General Hospital in Washington, D.C. Five years ago he became the first African-American vice president of the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute of Tampa.Surviving are a daughter, Leslie Wood of St. Louis; his father, Wardell; a brother, Jerry; and a sister, Patricia Baxter