April 12, 2003 - PCOL Exclusive: Every city is a village: Recommendations for the Digital Freedom Initiative

Peace Corps Online:

Peace Corps News:

Headlines:

Peace Corps Headlines - 2003:

April 2003 Peace Corps Headlines:

April 12, 2003 - PCOL Exclusive: Every city is a village: Recommendations for the Digital Freedom Initiative

Every city is a village: Recommendations for the Digital Freedom Initiative

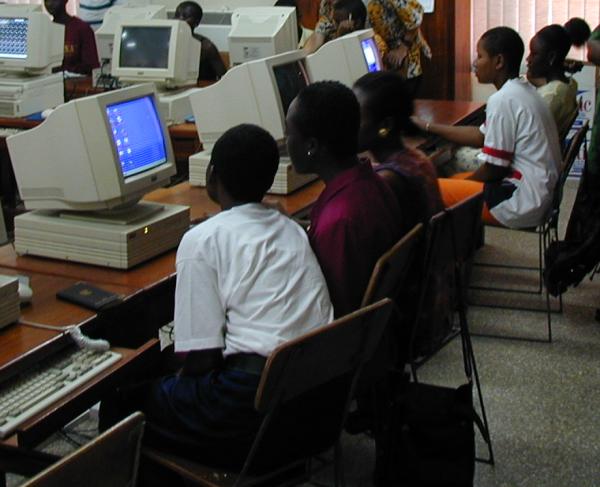

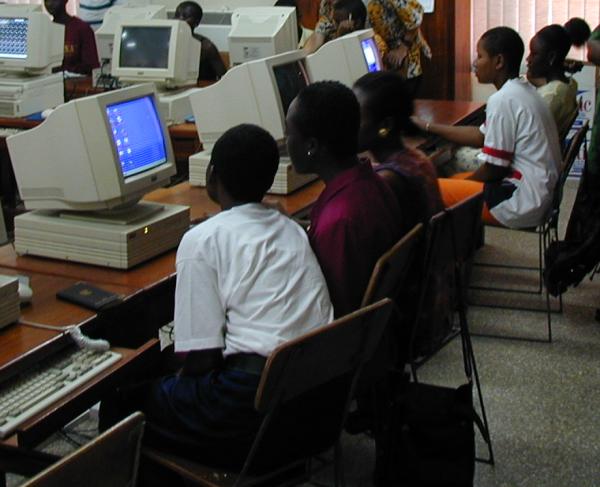

Figure 1. The urban and more affluent schools in West Africa have been able to set up computer labs for their students.

On March 4, 2003, the White House announced the Digital Freedom Initiative - a joint project between the Commerce Department, USAID, the Peace Corps, and private industry to promote economic growth by transferring the benefits of information and communication technology (ICT) to entrepreneurs and small businesses in the developing world and announced that DFI will be piloted in Senegal with 100 volunteers assisting small businesses and entrepreneurs in growing their businesses. If the project is successful, it will rolled out to 20 countries in the next five years.

Read and comment on this exclusive story written by Trevor Harmon, a volunteer who served as a math and physics teacher in Ghana from 1999 to 2001 and is now studying for his Ph.D. in Computer Science at the University of California at Irvine. The article explains the current state of computer technology in West Africa and how it could change as a result of DFI; it dissects DFI's stated goals and speculates on the potential for DFI's success; and it highlights a few possible shortcomings in DFI and gives recommendations for future projects. Read the article at:

Every city is a village: Recommendations for the Digital Freedom Initiative*

* This link was active on the date it was posted. PCOL is not responsible for broken links which may have changed.

Every city is a village: Recommendations for the Digital Freedom Initiative

By Trevor Harmon

April 6, 2003

Since 1961, the Peace Corps has been sending volunteers to Ghana, West Africa, to work in education, business development, and environmental protection projects. Most of these volunteers work in remote areas where poverty is extreme and the small rural communities have the greatest need for teachers, engineers, and other skilled professionals. I was surprised, then, when I learned that the Peace Corps had placed a volunteer in Accra, the largest and wealthiest city in Ghana, to teach computer literacy at an upscale high school. I asked a Ghanaian friend why Accra should get computer experts when the villages up north must surely have the greater need for computer skills and information technology.

"When you're talking about computers in Africa," he said, "every city is a village."

This simple statement explains the motivation behind the Digital Freedom Initiative (DFI), an ambitious new project sponsored by the U.S. Department of Commerce. Beginning with a three-year, $6.5 million pilot program in Senegal, its long-term goal is to bring the benefits of computer technology and Internet access to developing countries. Several government agencies are participating, including the Peace Corps, USAID, and the USA Freedom Corps. Private companies are also welcome to join the project. Hewlett-Packard and Cisco, two of the largest computer technology companies in the world, have already signed on.

As a pilot project, DFI is still quite new, and the details of its implementation have not been made public. Several documents are available on the DFI website1, but because the project is in its early stages, these documents are short on specifics. Instead, they offer plenty of nebulous phrases such as "enable innovation", "leverage leadership", and "enhance business competitiveness". Likewise, the press releases from Hewlett-Packard and Cisco claim that they will "co-invent locally relevant IT solutions" and "fuel technical education". Exactly how these organizations will accomplish such monumental tasks is unclear.

The dot-com boom and bust proved that computers and Internet access are not goals in themselves; they are merely tools. The directors of DFI should be careful not to fall into the trap of providing web browsers and disk drives to developing countries and simply hoping that economic prosperity will follow. Still, if every city in the developing world is a technological village, then even a little bit of progress can have a big impact. With the right planning, DFI can provide a foundation for growth in countries like Senegal and Ghana while helping to satisfy the global need for computer technology.

In the paragraphs that follow, I'll explain the current state of computer technology in West Africa and how it could change as a result of DFI. I'll also dissect the DFI's stated goals and speculate on their potential for success. Finally, I'll highlight a few possible shortcomings and offer some recommendations for future projects.

Computer Access In West Africa

Today, access to computers in West Africa is at about the same level that it was in the United States during the mid-1980s. Large banks in the region use computers for processing transactions, government agencies track documents and records with computer databases, and many high schools have at least one computer on campus for administrative tasks or the science lab (see Figure 1). In the home, however, computers are still a luxury available only to the wealthy. The concept of a "personal" or "family" computer does not exist, or at least is a very new phenomenon, just as it was in 1984 when the first Apple Macintosh went on sale in the U.S.

The perception of computers by the general public is also similar to that of the American public fifteen years ago. Many West Africans understand the need for computer technology in business, science, and education, but most aren't sure how computers can help them in their daily lives. Clearly, this perception comes from simple economics. When a computer can cost as much as the average annual salary in West Africa, the benefits of owning one are hard to justify.

But if there are indeed true benefits in bringing computer technology to the region, then the solution is not just a matter of overcoming poverty. As the creators of DFI have recognized, developing countries lack the skilled workers that are needed to grow and sustain a computer industry. The schools, too, lag far behind the developed world in teaching basic computer literacy. Knowledge of computers is rare among young people in West Africa, and many schoolchildren have never even seen a computer.

Despite this shortage of computer know-how, or perhaps because of it, I discovered a genuine hunger for computers in both children and adults during my two-year stay in West Africa. The Peace Corps had placed me in a high school in a small rural town of Ghana, and I occasionally found time to teach basic computer classes for my students in the evening. By chance, I was able to assemble an ad-hoc computer lab using the the six computers provided to the school by Ghana's Ministry of Education. (None of the local faculty knew how to operate the computers, so they were just collecting dust when I found them.)

The very first lesson remains clear in my mind: I gave no lecture; I simply allowed the students to play Solitaire on the computers. The idea was to give the students some practice with the mouse and reduce any apprehension they might have about technology--some were afraid to touch the computer for fear of breaking such an expensive machine. I also wanted to prove to them that a computer can be a tool for recreation, not just for business or learning.

To my surprise, the students needed little encouragement. Some of them brought cameras and posed for each other in front of the computers, smiling, hands hovering over the keyboard to give the impression that they knew how to type. Later, when I showed them how the computer can record and playback sounds, several of the girls began singing their favorite gospel tunes into the microphone, turning the class into an impromptu recording studio (see Figure 2). The computer classes became so popular that I later got requests from faculty members for private lessons.

Figure 2. Multimedia is a wonderful catalyst to get students interested in computer literacy.

If this experience is any guide, the Digital Freedom Initiative should have no trouble convincing the public of the benefits of computer technology. It shows that the scarcity of computers in Ghana, as well as Senegal and other developing countries, is clearly not a lack of motivation but a problem of economics and education. Computers are simply too expensive for these countries, and not enough people know how to harness the technology even when it is available.

Time to catch up

Naturally, developed countries are not immune to these very same issues. In the United States, for example, there is concern over the "digital divide" between the suburbs and the inner-city. This gap, however, is much narrower than it was a decade ago.2 Today, a basic home computer is affordable even for low-income American families--Wal-Mart sells them for $300--and virtually every high school in the country now has a computer lab of some kind. A more fundamental change is that computers have become nearly universal in American life, so there is a general appreciation of the benefits of computer technology and, perhaps more importantly, its limitations. This emergence of computers in business, education, and the home has occurred largely over the last fifteen years or so, which leaves developing countries about fifteen years behind.

Fortunately, such countries do not need fifteen years to catch up. They can leapfrog obsolete inventions and dead-end ideas, focusing only on technology that is known to work and is still relevant today. For instance, a Ghanaian acquaintance once told me that he was teaching himself MS-DOS, the Microsoft Disk Operating System, an unfriendly command-line environment. He said that people in developed countries had studied this system first before moving to its successor, Microsoft Windows, and he had therefore decided to study MS-DOS, as well. He didn't realize that it had since become extinct and is useful today only in a few arcane situations.

In a similar vein, dial-up Internet access over telephone lines is fast becoming out-of-date. Huge investments in upgrading to faster modems and increasing the number of dial-up access points are now going to waste. These days, the new standard is broadband Internet access through cable modem, satellite, or Digital Subscriber Line (DSL), and many homes and businesses are ditching their old analog modems. West Africa, on the other hand, has relatively little investment in dial-up networks, so it faces the unique opportunity of skipping the entire upgrade cycle and jumping directly to a broadband infrastructure.

So, in a certain sense, this lack of computer technology and infrastructure in West Africa could actually make development projects such as DFI a little bit easier to implement. The entire region is fertile ground for well-planned projects that avoid the mistakes and missteps of the past. With keen hindsight, plus a little help from developed countries, West Africa could slingshot itself into the digital age.

Communication centers are the key

If West Africa is years behind in computer technology, then the obvious goal of any development initiative is to close the gap. The DFI could be the kind of project that helps reach this goal. According to information in press releases and other public documents, it offers several new and fundamentally different strategies that set it apart from previous attempts at bridging the digital divide. One DFI objective in particular looks very promising: "Leverage existing information and communications infrastructure to promote economic growth."3

This idea, vague though it may be, makes a lot of sense. Past initiatives4 have attempted to copy ideas and business models from North America and Europe and apply them to West Africa, but these models are not always viable given the unique situation of developing countries. For example, the mantra of a certain U.S. software company is: "A computer on every desk and in every home".5 Although this business model has worked well in the affluent United States, where many families earn enough income to purchase a home computer, trying to provide a computer for the majority of families in a developing country would almost certainly be a non-sustainable effort.

Instead, the DFI should look to an existing model that has already been proven to work for another kind of expensive technology: the telephone. A residential telephone line is a luxury item in West Africa, and as a result, the so-called "communication center" has flourished even in the smallest of towns. These centers are nothing more than small shops that include at least one telephone (usually a fax machine, as well) and offer pay-per-minute telephone service to many who could not otherwise afford it. More than just payphones, these centers are private businesses that generate profit for their owners while sharing among the whole community the high cost of telecommunication.

With so many of these businesses already in place, the DFI could "leverage existing infrastructure" by promoting the use of computers at communication centers. Indeed, some centers located in the cities have already installed a computer or two, but the smaller centers, especially those in more rural areas, are still struggling to upgrade their services with computer technology. DFI could play a role here by providing computer training, installation support, and perhaps some type of financing to help local entrepreneurs overcome the steep cost of computer hardware. It could also promote open-source software6, such as Linux7 and OpenOffice8, as a cheaper alternative to commercial software packages costing hundreds of dollars each9.

The demand for these shared computers should grow as more people in the region become computer literate and discover the value of information technology. For example, a Peace Corps volunteer working in central Ghana discovered that funerals, a cornerstone of West African life, can be an unlikely source of income for entrepreneurs armed with a computer and a printer. She helped start a small but profitable business in her community that produced full-color funeral invitations for the recently bereaved. Similar business opportunities (but hopefully not quite so morbid) should appear in West Africa's computer industry over time and help accelerate the growth of its economy.

Internet for the masses

Computers, printers, and a few solid business plans will surely help this economy, but they will not be enough to make it competitive in the global marketplace. If West Africa is to reach that kind of goal, it will also require better access to the Internet. Luckily, the Internet seems to be exploding all over the region. Senegal, for instance, became the proud new recipient last year of a fiber-optic Internet backbone. This undersea cable, which joins Senegal to fifteen other countries in Africa, Europe, and Asia, provides enough high-speed Internet service for the entire population.10

The DFI has appeared at the perfect time for Senegal to take advantage of this new Internet backbone. DFI volunteers could apply their networking skills in helping local Internet service providers extend the backbone throughout the interior of Senegal. Laying fiber-optic lines to every town and city would be too expensive, of course, so a hybrid approach would be the best alternative. For example, the government could provide the funding for high-capacity data lines running only between the largest cities, and private businesses could then step in to provide cheaper, slower connections linking sites within those cities to central access points.

A possible medium for these intra-city links is Wireless Fidelity, or Wi-Fi. Wi-Fi is an umbrella term that refers to any type of wireless networking equipment operating in the 2.4 GHz or 5 GHz radio frequencies.11 Because these frequencies don't require licenses, the equipment is very inexpensive, and as a result, the popularity of Wi-Fi has risen while prices continue to drop. Today, wireless Internet access can be delivered to remote sites up to twenty miles away for about $200, making Wi-Fi an excellent match for West Africa.12 Senegal could, with help from the DFI, build inexpensive Wi-Fi networks that mesh together dozens of communication centers throughout a city. Sharing a single high-capacity access point in this manner would boost Internet connections to broadband speeds while avoiding the high cost of dial-up.

No technology without deregulation

A convenient side-effect of fast, always-on Internet access is the possibility of VoIP, or "Voice over the Internet Protocol". Simply put, it allows telephone conversations to take place over the Internet rather than over traditional copper lines. Although the sound quality of VoIP is worse than standard telephone service, it costs far less. Net2Phone13, for instance, provides Internet software that allows computer users in Senegal to call anyone in the United States for just ten cents per minute. If both parties have a computer, then calls can be made completely free using software such as PC-Telephone14. VoIP service is already popular in some Internet cafés in West Africa.

The shift from standard phone service to VoIP has hit a few regulatory speed bumps. Many West African countries, in an attempt to protect their government-owned telephone monopolies, have imposed strict controls over any company offering voice communication, in effect making VoIP illegal. In Ghana, an Internet service provider was jailed for providing VoIP service15.

These draconian policies have made the second goal of DFI, to "promote pro-growth regulatory structures", my favorite. It is a reminder that technology alone cannot solve the problems faced by developing countries. For the DFI to work, it will also need to begin tearing down long-standing ivory towers in the governments of those countries: high import tariffs, large bureaucracies, and a resistance to privatization of public industries. Such hurdles can prevent technology from entering West Africa and allowing it to thrive. Imported computer equipment, for example, even when donated to a non-profit organization, can be held up in customs for months while waiting for the proper documents to work their way through the system.16 By helping to eliminate obstacles like these, the DFI will make its work, as well as all future initiatives, easier and more effective.

Not the final answer

The Digital Freedom Initiative is a noble step in the right direction. It should help bring about an evolutionary change in the way developing countries use computer technology, but it still lacks a few vital components.

Most notably, it offers no plans for education. Computer literacy among the public is absolutely necessary if the initiative is to remain sustainable and have an effect over the long term. Until the level of computer literacy in a developing country reaches critical mass, any large-scale benefits promised by DFI may not appear. This does not mean that the initiative needs to produce computer scientists and electrical engineers, but it should at least strive to increase basic knowledge of computers, especially among younger people.17 In this new generation is where the real technology revolution is taking place in West Africa, and it is where the DFI should focus its efforts.

For example, a development agency called ActionAid, known for its strong presence in West Africa, sponsors after-school clubs to promote AIDS education and prevention. The idea is to help students grow more comfortable with complicated subjects, expose them to basic facts, and simply make learning a little more fun. In the same manner, the DFI could sponsor high school computer clubs, set up computer labs on campus, and train faculty in computer literacy so that local teachers can run the labs, thus making the project sustainable.18 Unfortunately, the DFI appears to have neglected the importance of general computer literacy in the communities where it will operate.

Another strangely absent component of the DFI is funding for computer hardware. The initiative's goal is to bring computer skills to developing countries, but such skills may have little value with so few computers available to those countries (see Figure 3). While the initiative should be applauded for not donating computers blindly and without regard to providing skills19, it seems to have gone to the opposite extreme by providing training alone and overlooking the difficulty of purchasing a computer in a developing country.

Figure 3. With so few computers in West Africa, the DFI's efforts may not have much of an impact.

The DFI need not become a charity in order to solve this problem. Instead, it would only need to offer some financial aid to those who want to purchase a computer. For instance, a partnership between DFI and local banks could provide low-interest loans to families who want to buy a home computer. Another possibility is a fund-matching program with the national governments of West Africa: For every two computers that a government buys for a public library or school, the DFI would provide funds for the purchase of a third computer. Programs like these would avoid the climate of dependency that comes from charity while still offering financial help and an incentive for individuals and governments to purchase computers on their own.

But perhaps the most essential part of the DFI has nothing to do with development work. It is a pilot project, after all, so its degree of success will decide whether it will expand to countries beyond Senegal. It will also guide the path of future technology development projects funded by other agencies and countries. A reliable and objective measure of its success is therefore mandatory. The DFI says it will judge its success by "performance benchmarks that measure small business growth, market efficiency gains, business integration with international partners and markets, and job growth."20

These criteria are rather hazy and are not directly related to the level of access to computer technology in a developing country. In fact, such benchmarks will likely improve independently of the DFI. They are purely economical indicators, and the economies of Senegal and other developing countries should continue to grow even without the support of the DFI. True performance benchmarks would include statistics such as the number of computers purchased from year to year, number of Internet access accounts in service, and the ability of graduating high school students to perform well on tests of computer literacy.

Despite these shortcomings, the DFI looks to be a superb project overall. It recognizes the importance of matching initiatives to the specific needs of developing countries, rather than trying to shoehorn a particular project into them just because it worked in the industrialized world. It also attempts to work at the grassroots level through individual businesses, rather than through a government bureaucracy, which should make its work more effective and longer lasting. Even if the DFI pilot project is judged a failure, it will at least have drawn more attention to the computer technology gap in developing countries.

About the Author

Trevor Harmon served in the Peace Corps from 1999 to 2001 as a math and physics teacher in Ghana, West Africa. He is currently working on a Ph.D. in computer engineering at the University of California, Irvine. He can be reached at trevor@vocaro.com.

Footnotes

1. See: http://www.dfi.gov

2. A study conducted by Grunwald Associates claims that Internet use among minority and low-income children in the U.S. is rapidly increasing, as reported by Reuters. See: "'Digital divide' shrinks among U.S. kids", http://www.cnn.com/2003/TECH/internet/03/20/digital.divide.reut/

3. The unabridged statement is "Leveraging existing technology and communications infrastructure in new ways to help entrepreneurs and small businesses better compete in both the regional and global market place." See: http://www.dfi.gov/pages/about.html|

4. In the Philippines, an aid-funded project to introduce a health information system was designed according to a Western model that assumed the presence of skilled programmers, skilled project managers, a sound technological infrastructure, and a need for information outputs like those used in an American health care organization. In reality, none of these was present in the Philippine context and the information system failed. See: http://idpm.man.ac.uk/wp/di/di_wp11.htm

5. Bill Gates, Microsoft Corporation: "We started with a vision of a computer on every desk and in every home...Every day, we're finding new ways for technology to enhance and enrich people's lives. We're really just getting started." See: http://microsoft.com/mscorp/articles/profile.asp

6. Open-source software is designed and built through public collaboration. Anyone can modify, distribute, and use open-source software free of charge, making it ideal for developing countries. See: http://www.opensource.org

7. Linux is a Unix-like operating system created by Linus Torvalds with the assistance of developers around the world. Developed under an open-source license, Linux is freely available to everyone. See: http://www.linux.org/

8. OpenOffice is a suite of productivity software including a word processor, spreadsheet, presentation manager, and drawing program. Though very similar to the Microsoft Office software package, it is open-source and can be used free of charge. See: http://www.openoffice.org/

9. Based on a sample of current retail prices, the Microsoft Windows operating system and Microsoft Office productivity suite cost around $625 per user. The Linux operating system and OpenOffice suite, though not quite as polished or user friendly as their Microsoft counterparts, are completely free.

10. Initially, the bandwidth of the cable is twenty gigabytes per second, nearly thirty times the total previous bandwidth for all of Africa. Plans are in the works to upgrade capacity to 120 gigabytes per second, the equivalent of 5.8 million simultaneous telephone calls. See: http://www.worldmarketsanalysis.com/sample_pages/5.html

11. Wireless networking equipment based on the Wi-Fi standard is also known as 802.11a (5 GHz), 802.11b (2.4 GHz), or 802.11g (2.4 GHz). See: http://www.80211-planet.com/

12. With the addition of high-gain directional antennas, two Wi-Fi networking cards or access points can communicate at distances of up to 30 kilometers with minimal signal loss. See: http://www.oreillynet.com/pub/a/wireless/2001/05/03/longshot.html

13. Net2Phone, Inc. offers PC-to-phone telephony software and calling cards that use VoIP networks. See: http://www.net2phone.com

14. PC-Telephone sells software that can make unlimited PC-to-PC calls without any additional charges. See: http://www.pc-telephone.com

15. According to Balancing Act, an African development advocacy group, a Ghanaian named Francis Quartey was jailed for allegedly providing VoIP services through his ISP. See: http://www.balancingact-africa.com/news/back/balancing-act_145.html

16. This happened to a friend of mine in the Peace Corps. She had managed to get her relatives and friends to donate four computers and have them shipped to the school where she was teaching. When the computers arrived in Ghana, they wallowed in customs for two months while the government sorted through the paperwork proving that the computers were actually donations and not for sale. The students weren't able to use the computers until the following semester.

17. While teaching an after-school computer class in Ghana, I discovered some cultural differences that make learning how to use a computer a bit more difficult for young people in West Africa. For example, my students often brought a "white board" to my regular classes during the day. These boards are thin, paper-sized pieces of wood painted white and coated with a clear varnish. The students take notes on them in pencil, then erase them using a mixture of soap and water. It saves them money because they don't need to waste paper on scratch work and practice problems. But in the evenings, when I tried to teach them how to use a word processor, I learned that they carried this concept of a "white board" a bit too far. Instead of simply closing an unwanted document, they would carefully erase every word that they had typed by holding down the Backspace button. I had to explain carefully that a computer screen does not need erasing. For more reflections on this experience, see: http://vocaro.com/trevor/peacecorps/girlsclub

18. Finding volunteers to teach computer literacy should not be difficult. The typical Peace Corps volunteer, for instance, is a computer expert by West African standards simply because she knows how to surf the web, send email, and tell the difference between a word processor and a spreadsheet. Passing on these basic skills is all that would be needed.

19. Carly Fiorina, Hewlett-Packard chairman and chief executive officer, said in a press release: "The Digital Freedom Initiative makes it clear that financial capital alone is not the greatest wealth multinationals can bring to the developing world; it is human capital. It is experience and knowledge and the ability to use those skills to empower local communities. It is using technology not as an end in itself but as an enabler to address fundamental problems of hunger, disease and economic development." See: http://www.hp.com/hpinfo/newsroom/press/2003/030304d.html

20. The unabridged statement is: "At regular intervals, DFI projects will be evaluated based on performance benchmarks that measure small business growth, market efficiency gains, business integration with international partners and markets, and job growth." See: http://www.dfi.gov/pages/about.html

Copyright © 2003 Trevor Harmon

Click on a link below for more stories on PCOL

4/11/03

Some postings on Peace Corps Online are provided to the individual members of this group without permission of the copyright owner for the non-profit purposes of criticism, comment, education, scholarship, and research under the "Fair Use" provisions of U.S. Government copyright laws and they may not be distributed further without permission of the copyright owner. Peace Corps Online does not vouch for the accuracy of the content of the postings, which is the sole responsibility of the copyright holder.

This story has been posted in the following forums: : Headlines; Internet; Computers; Digital Freedom Initiative; COS - Ghana; COS - Senegal

PCOL4209

94

.

You might like to know a little background to the reason the 6 PCs were in the school mentioned in the article.

The Ghanaian Ministry of Education contracted a British company, Philip Harris International, to set up a network of Science Resource Centres (SRC) in Ghana at a cost of some GBP19.75 million. The project involved the provision of science equipment, chemicals, PCs and even datalogging equipment to about 20% of Ghana's seondary schools.

Each SRC was supplied with a 45-seater school bus to transport students from satellite schols to the SRC for science practical lessons.

I was one of two installation engineers tasked with installing the science equipment and PCs in 110 schools in Ghana, including several in Accra, between 1995 and 1998. Each school received 6 PCs preinstalled with Windows 3.1, MS Office and a range of multimedia packages. The PCs were fitted with filters and adapted to better withstand the dusty conditions and uninterruptable power supply units and printers were supplied. Internet access in Ghana began to become available over the time I was there but this was too late to be incorporated into the project.

It is interesting that the author reports that in 1999 there were no staff capable of using the PCs. As part of the project, staff from Solihull College in the UK travelled toGhana and ran six residential training courses, each six weeks long and trained over 700 Ghanaian teachers in basic IT skills and the use of other equipment supplied to the SRCs. In addition, my colleague and I were available to give advice and technical support in Accra, and during our frequent travels round the country installing other centres. Teaching is not a prestigious career in Ghana and anecdotal evidence suggested at the time that at least some teachers, especially in rural areas, left the profession and used their new-found IT skills to find (relatively) more lucrative jobs in the city.

Wi-Fi networks are great.However,in small town with no any kind of telecom infrastructure,what will you use for backbone/back-aul?

Julius.

|

By Helene (82.198.1.64.satgate.net - 82.198.1.64) on Saturday, March 06, 2004 - 5:45 am: Edit Post |

Very nice site. Please take a look also to calling cards at www.connectto.com.

Thank you.

Hello

I will be very greatful if I can have a full information about the peace corps working in Accra City, their palce of work so I can get intouch.I will be happy to read from you.

Alfred

|

By Anonymous (69-174-88-2.chvlva.adelphia.net - 69.174.88.2) on Saturday, June 24, 2006 - 4:40 am: Edit Post |

MR. KUMAH

I HAVE A QUESTION: I WOULD LIKE TO KNOW IF YOU THINK OR FEEL THAT IT WILL BE POSSIBLE THAT A WALMART COULD BE OPENED IN GHANA, WEST AFRICA. ACCURA?

|

By Anonymous (adsl-tplus-90-212.telecomplus.net - 196.27.90.212) on Sunday, October 15, 2006 - 8:03 am: Edit Post |

Dear Sir,

ABOUT OUR COMPANY

VFC (Virus Free Computer)

none any virus, Trojan, spyware and addware

can damage the entire system.

http://www.fumaxtech.com

VFC (Virus Free Computer) is based on the concept of Network Computer initiated in 1995, the CEO of Oracle. Being able to take the effectiveness of Network Computer, VFC not only rules as a personal computer but also can share the network activities, including the resource of software and hardware. In 1999, VFC was the first announced using the network card as the linkage for data transfer mode. Furthermore VFC was announced as a complete PC system in 2004.

Virus Free Computer Applications

It's ok for chat and access internet

Hotel, Coffee Shop, Bus Station, MTR, Airport, Department Store, Exhibition, Inquiry Stand, Shopping Mall, Recreating Center, Sauna Center, Library, Public Area, School,

Nursery Center, Computer Center, Media Center, Internet Cafe, Family, Community, Commercial Bank, Securities Bank,Finnacial Market, Government Department,

Cooperation.

Fumax Technology Ltd infrastructure and its information technology can help your business on the path of prosperous in safety network. Welcome to join us four-win business --- Partner, Customer, Client and Enterprise.

Regards

Mansoor

FUMAX THECHNOLOGY LTD

Royal Road Nouvelle Découverte Saint Pierre MAURITIUS

Fax : 230 4315929 Email : fumax@intnet.mu

http://www.fumaxtech.com

I SHALL BE GLAD IF THE ORGANIZATION CAN RUN THE PROFESSIONAL BOBY WITH ME HERE IN WEST AFRICA GREAT NIGERIA, AND TO OPERATE IT FOR THE YOUNG MESSERS.

THANKS.

MR MIKE ISICHEI