Looking back, it is clear that the strength of America’s military forces and intelligence capabilities – along with the willingness to use them – held the Soviets at bay for more than four decades. But there was another side to that story and to that struggle. There was the Agency for International Development overseeing development and humanitarian assistance programs that improved – if not saved – the lives of millions of people from disease, starvation, and poverty. Our diplomats forged relationships and bonds of trust, and built up reservoirs of expertise and goodwill that proved invaluable over time. Countless people in foreign countries wandered into a United States Information Agency library, or heard from a visiting speaker and had their opinions about America transformed by learning about our history and culture and values. Others behind the Iron Curtain were inspired to resist by what they heard on Radio Free Europe and the Voice of America. In all, these non-military efforts – these tools of persuasion and inspiration – were indispensable to the outcome of the defining ideological struggle of the 20th century. I believe that they are just as indispensable in the 21st century – and maybe more so. It has become clear that America’s civilian institutions of diplomacy and development have been chronically undermanned and underfunded for far too long – relative to what we spend on the military, and more important, relative to the responsibilities and challenges our nation has around the world. I cannot pretend to know the right dollar amount – I know it’s a good deal more than the one percent of the federal budget that it is right now. But the budgets we are talking about are relatively small compared to the rest of government, a steep increase of these capabilities is well within reach – as long as there is the political will and wisdom to do it.

Robert M. Gates says: Tools of persuasion and inspiration – were indispensable to the outcome of the defining ideological struggle of the 20th century

U.S. Global Leadership Campaign (Washington, D.C.)

As Delivered by Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates, Washington, D.C. , Tuesday, July 15, 2008

Thank you very much for the introductions.

Thank you Condi Rice for the kind words, and above all, for your principled and visionary leadership of the Department of State.

One of the reasons I have rarely been invited to lecture in political science departments – including at Texas A&M – is because faculty correctly suspect that I would tell the students that what their textbooks say about government does not describe the reality I have experienced in working for seven presidents. Organization charts, institutions, statistics, structures, regulations, policies, committees, and all the rest – the bureaucracy, if you will – are the necessary pre-condition for effective government. But whether or not it really works depends upon the people and their relationships. For significant periods since I entered government 42 years ago, the Secretary of State and Secretary of Defense were not on speaking terms. The fact that Condi and I actually get along means that our respective bureaucracies understand that trying to provoke us to fight with one another is not career-enhancing. Such efforts still occur, of course. After all, this is Washington. But the bureaucratic battles are a good deal more covert.

Of course, the human side of government is always a source of both humor and embarrassment. Will Rogers once said, “I don’t make jokes. I just watch the government and report the facts.” And the conduct of diplomacy, where – as Secretary Rice can attest – protocol and propriety are so very important, provides an especially fertile ground for amusement.

For example, there was the time that President Nixon met with Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir, shortly after Nixon had appointed Henry Kissinger as Secretary of State. With Golda Meir in that meeting was her very erudite foreign minister, Abba Eban, a graduate of Cambridge. At one point in the meeting, Nixon turned to Golda Meir and said, “Just think, we now both have Jewish foreign ministers.” And without missing a beat Golda Meir said, “Yes, but mine speaks English.”

Then there was the time that President Nixon visited Italy and had a meeting with the Pope. Kissinger and Nixon had along with them Secretary of Defense Mel Laird, but they decided that Laird as, in effect, secretary of war shouldn’t be invited to meeting with the Pope. So, Nixon the next morning went in for his private audience with the Pope, and the other Americans waited outside for the general audience. And who should come striding down the hall of the papal apartments but Mel Laird smoking an enormous cigar, he had decided he wanted in on the meeting. Kissinger was beside himself, but finally said, “Well, Mel, at least extinguish the cigar.” And so Laird stubbed out his cigar and put it in his pocket.

The rest of the American party a few minutes later went in to their meeting with the Pope, everyone took a seat. A couple of minutes into the Pope’s remarks, Kissinger heard this little patting sound going on, he was in the second row with Laird on the end, there was a wisp of smoke coming out of Laird’s pocket. Everything seemed under control. A couple of minutes later, Kissinger heard this loud slapping noise. He looked over smoke was billowing out of Laird’s pocket. The Secretary of Defense was on fire. Now the rest of the delegation heard this slapping noise, and they thought they were being cued to applaud the Pope. And so they did. And Henry later told us, “God only knows what his Holiness thought, seeing the American secretary of defense immolating himself, and the entire American party applauding the fact.”

I am honored to receive this award, and I consider it a privilege to be associated with the United States Global Leadership Campaign. It is a truly remarkable collection of “strange bedfellows” – from Save the Children to Caterpillar, from Catholic Relief Services to AIPAC, and even Boeing and Northrop Grumman. This organization has been a prescient, and often lonely, advocate for the importance of diplomacy and international development to America’s vital national interests – and I commend you for that.

Though my views on these subjects have become better known through recent speeches, in many ways they originated and were reinforced by my prior experience in government during the Cold War. Looking back, it is clear that the strength of America’s military forces and intelligence capabilities – along with the willingness to use them – held the Soviets at bay for more than four decades. But there was another side to that story and to that struggle. There was the Agency for International Development overseeing development and humanitarian assistance programs that improved – if not saved – the lives of millions of people from disease, starvation, and poverty. Our diplomats forged relationships and bonds of trust, and built up reservoirs of expertise and goodwill that proved invaluable over time. Countless people in foreign countries wandered into a United States Information Agency library, or heard from a visiting speaker and had their opinions about America transformed by learning about our history and culture and values. Others behind the Iron Curtain were inspired to resist by what they heard on Radio Free Europe and the Voice of America.

In all, these non-military efforts – these tools of persuasion and inspiration – were indispensable to the outcome of the defining ideological struggle of the 20th century. I believe that they are just as indispensable in the 21st century – and maybe more so.

Just last month I approved a new National Defense Strategy that calls upon us to “Tap the full strength of America and its people” – military and civilian, public and private – to deal with the challenges to our freedom, prosperity, and security around the globe.

In the campaign against terrorist networks and other extremists, we know that direct military force will continue to have a role. But over the long term, we cannot kill or capture our way to victory. What the Pentagon calls “kinetic” operations should be subordinate to measures to promote participation in government, economic programs to spur development, and efforts to address the grievances that often lie at the heart of insurgencies and among the discontented from which the terrorists recruit. It will take the patient accumulation of quiet successes over time to discredit and defeat extremist movements and their ideology.

We also know that over the next 20 years and more certain pressures – population, resource, energy, climate, economic, and environmental – could combine with rapid cultural, social, and technological change to produce new sources of deprivation, rage, and instability. We face now, and will inevitably face in the future, rising powers discontented with the international status quo, possessing new wealth and ambition, and seeking new and more powerful weapons. But, overall, looking ahead, I believe the most persistent and potentially dangerous threats will come less from ambitious states, than failing ones that cannot meet the basic needs – much less the aspirations – of their people.

In my travels to foreign capitals, I have been struck by the eagerness of so many foreign governments to forge closer diplomatic and security ties with the United States – ranging from old enemies like Vietnam to new partners like India. Nonetheless, regard for the United States is low among the populations of many key nations – especially those of our moderate Muslim allies.

This is important because much of our national security strategy depends upon securing the cooperation of other nations, which will depend heavily on the extent to which our efforts abroad are viewed as legitimate by their publics. The solution is not to be found in some slick PR campaign or by trying to out-propagandize al-Qaeda, but rather through the steady accumulation of actions and results that build trust and credibility over time.

To do all these things, to truly harness the “full strength of America,” as I said in the National Defense Strategy, requires having civilian institutions of diplomacy and development that are adequately staffed and properly funded. Due to the leadership of Secretary Rice and before her Secretary Powell, and with the continuing strong support of the President, we have made significant progress towards pulling ourselves out of the hole created not only by the steep cutbacks in the wake of the Cold War – but also by the lack of adequate resources for the State Department and the entire foreign affairs account going back decades.

Since 2001, international affairs spending has about doubled, State has begun hiring again, billions have been spent to fight AIDS and malaria in Africa, the Millennium Challenge Corporation is rewarding better governance in the developing world, and Secretary Rice has launched a program of transformational diplomacy to better posture the diplomatic corps for the realities of this century. The President’s budget request this year, as Condi said, includes more than 1,100 new Foreign Service officers, as well as a response corps of civilian experts that can deploy on short notice. And, for the first time in a long time, I sense real bipartisan support in Congress for strengthening the civilian foreign affairs budget.

Shortfalls nonetheless remain. Much of the total increase in the international affairs budget has been taken up by security costs and offset by the declining dollar, leaving little left over for core diplomatic operations. These programs are not well understood or appreciated by the wider American public, and do not have a ready-made political constituency that major weapons systems or public works projects enjoy. As a result, the slashing of the President’s international affairs budget request has too often become an annual Washington ritual – right up there with the blooming of the cherry blossoms and the Redskin’s opening game.

As someone who once led an agency with a thin domestic constituency, I am familiar with this dilemma. Since arriving at the Pentagon I’ve discovered a markedly different budget dynamic – not just in scale but the reception one gets on the Hill. Congress often asks the military services for lists of things that they need, but that the Defense Secretary and the President were too stingy to request. As you can imagine, this is one congressional tasking that prompts an immediate and enthusiastic response.

It has become clear that America’s civilian institutions of diplomacy and development have been chronically undermanned and underfunded for far too long – relative to what we spend on the military, and more important, relative to the responsibilities and challenges our nation has around the world. I cannot pretend to know the right dollar amount – I know it’s a good deal more than the one percent of the federal budget that it is right now. But the budgets we are talking about are relatively small compared to the rest of government, a steep increase of these capabilities is well within reach – as long as there is the political will and wisdom to do it.

But even as we agree that more resources are needed, I believe that there is more to this problem than how much money is in the 150 Account. The challenge we face is how best to integrate these tools of statecraft with the military, international partners, and the private sector.

Where our government has been able to bring America’s civilian and the military assets together to support local partners, there have been incredibly promising results. One unheralded example, one you will not read about in the newspapers, is in the Philippines. There the U.S. Ambassador – Kristie Kenney – has overseen a campaign involving multiple agencies working closely together with their Philippine counterparts in a synchronized effort that has delegitimized and rolled back extremists in Mindanao. Having a strong, well-supported chief of mission has been crucial to success.

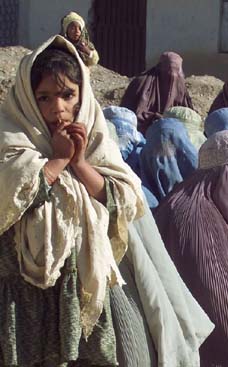

The vastly larger, more complex international effort in Afghanistan presents a different set of challenges. There are dozens of nations, hundreds of NGOs, universities, development banks, the United Nations, the European Union, NATO – all working to help a nation beset by crushing poverty, a bumper opium crop, and a ruthless and resilient insurgency. Getting all these different elements to coordinate operations and share best practices has been a colossal – and often all too often unsuccessful – undertaking. The appointment this spring of a UN special representative to coordinate civilian reconstruction in Afghanistan is an important step forward. And at the last NATO defense ministerial, I proposed a civilian-military planning cell for Regional Command South to bring unity to our efforts in that critically important part of the country. And I asked Kai Eide, when I met with him last week, to appoint a representative to participate in this cell.

Repeating an Afghanistan or an Iraq – forced regime change followed by nation-building under fire – probably is unlikely in the foreseeable future. What is likely though, even a certainty, is the need to work with and through local governments to avoid the next insurgency, to rescue the next failing state, or to head off the next humanitarian disaster.

Correspondingly, the overall posture and thinking of the United States armed forces has shifted – away from solely focusing on direct American military action, and towards new capabilities to shape the security environment in ways that obviate the need for military intervention in the future. This approach forms the basis of our near-term planning and influences the way we develop capabilities for the future. This perspective also informed the creation of Africa Command, with its unique interagency structure, a deputy commander who is an ambassador not a general, as well as Southern Command’s new orientation and priorities in Latin America.

Overall, even outside Iraq and Afghanistan, the United States military has become more involved in a range of activities that in the past were perceived to be the exclusive province of civilian agencies and organizations. This has led to concern among many organizations – perhaps including many represented here tonight – about what’s seen as a creeping “militarization” of some aspects of America’s foreign policy.

This is not an entirely unreasonable sentiment. As a career CIA officer I watched with some dismay the increasing dominance of the defense 800 pound gorilla in the intelligence arena over the years. But that scenario can be avoided if – as is the case with the intelligence community today – there is the right leadership, adequate funding of civilian agencies, effective coordination on the ground, and a clear understanding of the authorities, roles, and understandings of military versus civilian efforts, and how they fit, or in some cases don’t fit, together.

We know that at least in the early phases of any conflict, contingency, or natural disaster, the U.S. military – as has been the case throughout our history – will be responsible for security, reconstruction, and providing basic sustenance and public services. I make it a point to reinforce this message before military audiences, to ensure that the lessons learned and re-learned in recent years are not forgotten or again pushed to the margins. Building the security capacity of other nations through training and equipping programs has emerged as a core and enduring military requirement, though none of these programs go forward without the approval of the Secretary of State.

In recent years the lines separating war, peace, diplomacy, and development have become more blurred, and no longer fit the neat organizational charts of the 20th century. All the various elements and stakeholders working in the international arena – military and civilian, government and private – have learned to stretch outside their comfort zone to work together and achieve results.

For example, many humanitarian and international organizations have long prided themselves on not taking sides and avoiding any association with the military. But as we’ve seen in the vicious attacks on Doctors Without Borders in Afghanistan, and the U.N. Mission in Iraq, violent extremists care little about these distinctions.

To provide clearer rules of the road for our efforts, the Defense Department and “InterAction” – the umbrella organization for many U.S.-based NGOs – have, for the first time, jointly developed guidelines for how the military and NGOs should relate to one another in a hostile environment. The Pentagon has also refined its guidance for humanitarian assistance to ensure that military projects are aligned with wider U.S. foreign policy objectives and do not duplicate or replace the work of civilian organizations.

Broadly speaking, when it comes to America’s engagement with the rest of the world, you probably don’t here this often from a Secretary of Defense , it is important that the military is – and is clearly seen to be – in a supporting role to civilian agencies. Our diplomatic leaders – be they in ambassadors’ suites or on the seventh floor of the State Department – must have the resources and political support needed to fully exercise their statutory responsibilities in leading American foreign policy.

The challenge facing our institutions is to adapt to new realities while preserving those core competencies and institutional traits that have made them so successful in the past. The Foreign Service is not the Foreign Legion, and the United States military should never be mistaken for the Peace Corps with guns. We will always need professional Foreign Service officers to conduct diplomacy in all its dimensions, to master local customs and culture, to negotiate treaties, and advance American interests and strengthen our international partnerships. And unless the fundamental nature of humankind and of nations radically changes, the need – and will to use – the full range of military capabilities to deter, and if necessary defeat, aggression from hostile states and forces will remain.

In closing, I am convinced, irrespective of what is reported in global opinion surveys, or recounted in the latest speculation about American decline, that around the world, men and women seeking freedom from despotism, want, and fear will continue to look to the United States for leadership.

As a nation, we have, over the last two centuries, made our share of mistakes. From time to time, we have strayed from our values; on occasion, we have become arrogant in our dealings with other countries. But we have always corrected our course. And that is why today, as throughout our history, this country remains the world’s most powerful force for good – the ultimate protector of what Vaclav Havel once called “civilization’s thin veneer.” A nation Abraham Lincoln described as mankind’s “last, best hope.”

For any given cause or crisis, if America does not lead, then more often than not, what needs to be done simply won’t get done. In the final analysis, our global responsibilities are not a burden on the people or on the soul of this nation. They are, rather, a blessing.

Thank you for this award and I salute you for all that you do – for America, and for humanity.