In the seven years I've lived in this stronghold of the Afghan south - the erstwhile capital of the Taliban and the focus of their renewed assault on the country - most of my conversations with locals about what's going wrong have centered on corruption and abuse of power. "More than roads, more than schools or wells or electricity, we need good governance," said Nurallah during yet another discussion a couple of weeks ago. He had put his finger on the heart of the problem. We and our friends in Kandahar are thunderstruck at recent suggestions that the solution to the hair-raising situation in this country must include a political settlement with "relevant parties" - read, the Taliban. Negotiating with them wouldn't solve Afghanistan's problems; it would only exacerbate them. Ask any Afghan what's really needed, what would render the Taliban irrelevant, and they'll tell you: improving the behavior of the officials whom the United States and its allies ushered into power after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Morocco RPCV Sarah Chayes has made a home in Kandahar, Afghanistan, became fluent in Pashto, one of the main Afghan languages, and devoted her energies to rebuilding a country gutted by two decades of war.

Sarah Chayes writes: Failing Afghanistan

Sarah Chayes: Failing Afghanistan

by Sarah Chayes - Dec. 15, 2008 11:12 AM

Special to The Washington Post

KANDAHAR, Afghanistan - Nurallah strode into our workshop shaking with rage. His mood shattered ours. "This is no government," he stormed. "The police are like animals."

The story gushed out of him: There'd been a fender-bender in the Kandahar bazaar, a taxi and a bicycle among wooden-wheeled vegetable carts. Wrenching around to avoid the knot, another cart touched one of the green open-backed trucks the police drive. In seconds, the officers were dragging the man to the chalky dust, beating him - blow after blow to the head, neck, hips, kidneys. Shopkeepers in the nearby stalls began shouting, "What do you want to do, kill him?" The police slung the man into the back of their truck and roared away.

"So he made a mistake," concluded Nurallah, one of the 13 Afghan men and women who make up my cooperative. "We don't have a traffic court? They had to beat him?"

In the seven years I've lived in this stronghold of the Afghan south - the erstwhile capital of the Taliban and the focus of their renewed assault on the country - most of my conversations with locals about what's going wrong have centered on corruption and abuse of power. "More than roads, more than schools or wells or electricity, we need good governance," said Nurallah during yet another discussion a couple of weeks ago.

He had put his finger on the heart of the problem. We and our friends in Kandahar are thunderstruck at recent suggestions that the solution to the hair-raising situation in this country must include a political settlement with "relevant parties" - read, the Taliban. Negotiating with them wouldn't solve Afghanistan's problems; it would only exacerbate them. Ask any Afghan what's really needed, what would render the Taliban irrelevant, and they'll tell you: improving the behavior of the officials whom the United States and its allies ushered into power after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

I write this by flickering light, a fat candle at my right elbow and a kerosene lamp on my left. We get only three or four hours of electricity every couple of days, often from 1 to 5 a.m. Still, the bill has to be paid. To do that, you must wait in a total of eight lines in two different buildings. You almost never get through the whole process without hearing an uncouth bark as your turn comes up: "This desk is closing; come back tomorrow." Due to the electricity shortage, the power department won't open new accounts. Officially. But for $600 - 15 times the normal fee and a fortune to Afghans - you can get a meter installed anyway.

A friend recently visited the jail in Urozgan Province, north of Kandahar, where he found 54 prisoners. All but six were untried and uncharged and had been languishing there for months or years. A Kandahar public prosecutor told him how a defendant had once offered him the key to a Lexus if he would just refrain from interfering in a case the man had fixed.

Across the street from my cooperative there used to be a medical clinic. When it moved to a new facility, gunmen in police uniforms set up a checkpoint outside the empty building. Our inquiries revealed that they were the private guards of a senior government official. Their purpose? To serve as a graphic warning to the building's owners not to interfere in what would follow. A few days later, some friends of the official moved in. The owners had no say in the matter, no recourse. This government official is one of the men the United States helped put in power in 2001 and whom the international community has maintained and supported, no questions asked, ever since.

This is why the Taliban are making headway in Afghanistan - not because anyone loves them, even here in their former heartland, or longs for a return to their punishing rule. I arrived in Kandahar in December 2001, just days after Taliban leader Mullah Muhammad Omar was chased out. After a moment of holding its breath, the city erupted in joy. Kites danced on the air for the first time in six years. Buyers flocked to stalls selling music cassettes. I listened to opium dealers discuss which of them would donate the roof of his house for use as a neighborhood school. I, a barefaced American woman, encountered no hostility at all. Curiosity, plenty. But no hostility. Enthusiasm for the nascent government of Hamid Karzai and its international backers was absolutely universal.

Since then, the hopes expressed by every Afghan I have encountered - to be ruled by a responsive and respectful government run by educated people - have been dashed. Now, Afghans are suffering so acutely that they hardly feel the difference between Taliban depredations and those of their own government. "We're like a man trying to stand on two watermelons," one of the women in my cooperative complains. "The Taliban shake us down at night, and the government shakes us down in the daytime."

I hear from Westerners that corruption is intrinsic to Afghan culture, that we should not hold Afghans up to our standards. I hear that Afghanistan is a tribal place, that it has never been, and can't be, governed.

But that's not what I hear from Afghans.

Afghans remember the reign in the 1960s and 70s of King Zahir Shah and his cousin Daoud Khan, when Afghan cities were among the most developed and cosmopolitan in the Muslim world, when Peace Corps volunteers conducted vaccination campaigns on foot through a welcoming countryside, and when, my friends here tell me, a lone, unarmed policeman could detain a criminal suspect in a far-flung village without obstruction. Kandaharis - even those who lost a brother or father in the 1980s war against Soviet occupation - praise the communist-backed government of former president Najibullah. "His officials weren't building marble-clad mansions with the money they extorted," says Fayzullah, another member of my cooperative.

One day I asked three of my colleagues - villagers with almost no formal education - what jobs they would choose if we were the municipal government of Kandahar. They spoke right up. "I would want to be in charge of public hygiene," said Karim. "The garbage piling up on our streets is a disgusting health hazard." Abd al-Ahad wanted to be the registrar of public deeds, "so the big people can't just take land and pass it out to their cronies." Nurallah wanted to be the equivalent of the FDA: the man responsible for weights and measures and the quality of merchandise in the bazaar.

After the Soviet invasion, which cost a million Afghan lives over the course of the 1980s, followed by five years of gut-wrenching civil war and another six of rule by the Taliban, who twisted religious injunctions into instruments of social control, Afghans looked to the United States - a nation famous for its rule of law - to help them build a responsive, accountable government.

Instead, we gave power back to corrupt gunslingers who had been repudiated years before. If they helped us chase al-Qaida, we didn't look too hard at their governing style. Often we helped them monopolize the new opportunities for gain. A friend of mine, one of the beneficiaries, was astounded at the blank check. "What are we warlords doing still in power?" police precinct captain Mahmad Anwar asked me in 2002. "I vowed on the Holy Koran that I would fight the Taliban in order to bring an educated, competent government to Afghanistan. And now people like me are running the place?" I had to laugh at his candor.

Into the context of the white-hot frustration that has been building since then, insert the Taliban. Since 2001, they have been armed, financed, trained and coordinated in Pakistan, whose military intelligence agency - the ISI - first helped create them in 1994.

What I've witnessed in Kandahar since late 2002 has amounted to an invasion by proxy, with the Pakistani military once again using the Taliban to gain a foothold in Afghanistan. The only reason this invasion has made progress is the appalling behavior of Afghan officials. Why would anyone defend officials who pillage them? If the Taliban gouge out the eyes of people they accuse of colluding with the Afghan government, as they did recently in Kandahar, while the government treats those same citizens like rubbish, why should anyone take the risk that allegiance to Kabul entails?

More and more Kandaharis are not. More and more are severing contact with the Karzai regime and all it stands for, rejecting even development assistance. When Taliban thugs come to their mosques demanding money or food, they pay up. Many actively collaborate, as a means of protest.

The solution to this problem is not to bring the perpetrators of the daily horrors we suffer in Kandahar to the table to carve up the Afghan pie. (For no matter how we package the idea of negotiating with the Taliban, that's what Afghans are sure it will amount to: cutting a power-sharing deal.)

The solution is to call to account the officials we installed here beginning in 2001 - to reach beyond the power brokers to ordinary Afghan citizens and give their grievances a fair hearing. If the complaints prove to be well founded, Western officials should press for redress, using some of their enormous leverage. The successful mentoring program under which military personnel work side-by-side with Afghan National Army officers should be expanded to the civilian administration. Western governments should send experienced former mayors, district commissioners and water and health department officials to mentor Afghans in those roles.

If the United States and its allies had fulfilled their initial promise and pushed the Afghan government to become an institution its people could be proud of, the "reconcilable" Taliban would come into the fold of their own accord. The Afghans would take care of the rest.

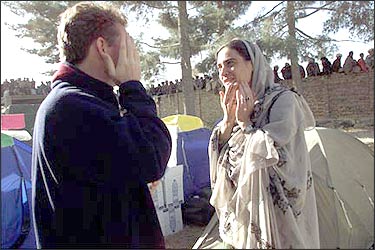

Sarah Chayes, the author of "The Punishment of Virtue: Inside Afghanistan After the Taliban," runs an Afghan cooperative that produces skin-care products.