Perhaps Saakashvili believed that, with the world's eyes on the opening of the Olympic Games in Beijing, he could launch a lightning assault on South Ossetia and reclaim the republic without substantial grief from Moscow, as he had Ajaria in 2004. His statements once the war began demonstrated that he expected real Western help in confronting Russia. Whatever prompted him to miscalculate, the strategic realities ignored by the Bush administration in pumping up Saakashvili's ambitions reasserted themselves as soon as Moscow responded to Saakashvili's gambit with the largest military assault, by land, sea, and air since the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979. Within days, Georgia lost both South Ossetia and Abkhazia to Russia, two thousand Georgians were dead, tens of thousands had been displaced, foreigners were being evacuated, and Gori and Tbilisi, their airports bombed, appeared threatened.

As Russian bombs rained down on Georgia and Saakashvili pleaded for help from the West and for a cease-fire from Moscow, Putin stated bluntly that "Georgia's aspiration to join NATO . . . is driven by its attempt to drag other nations and peoples into its bloody adventures," and warned that, "the territorial integrity of Georgia has suffered a fatal blow." The Bush administration answered with boilerplate language of protest, failing even to dispatch Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice to the region until six days later for rounds of shuttle diplomacy. Saakashvili complained that "all we got so far are just words, statements, moral support, humanitarian aid." But neither the United States nor Europe will risk Armageddon for Georgia. For Saakashvili, game over.

Jeffrey Tayler writes: The pitiable David-and-Goliath asymmetry of Georgia's dustup with Russia, plus Saakashvili's repeated hyperbolic declarations to satellite news stations, have obscured both the United States' culpability in bringing about the conflict, and the nature of the separatism that caused it in the first place

At Putin's Mercy

Georgia's forty-year-old president, the liberal Mikheil Saakashvili, may possess many admirable attributes - dashing looks, fluency in several languages (including English), a degree from Columbia Law school, and a heartfelt commitment to a Westward-looking future for his country - but strategic acumen, even plain old-fashioned common sense, do not, it is now tragically apparent, figure among them. Rather, Saakashvili is well-known in Georgia for his authoritarian streak and hotheadedness - the most damning character flaws imaginable in a confrontation with the calculating former spymaster and current Russian prime minister Vladimir Putin.

Saakashvili won presidential elections in 2004 promising to impose Tbilisi's writ on the three Russia-backed rebellious republics of Ajaria, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia. In short order, without firing a shot, he reclaimed Ajaria and sent its leader, Aslan Abashidze, fleeing to Moscow. But his reckless decision last week to shell and then invade South Ossetia (populated mostly by ethnic Ossetes holding Russian passports) and attack Russian forces stationed there, combined with his now obviously misplaced faith in the senior Bush administration officials, including President Bush himself, who have been glad-handing him since he came to power following the Rose Revolution of 2003, may yet undo his presidency and return Georgia to Russian vassalage.

The pitiable David-and-Goliath asymmetry of Georgia's dustup with Russia, plus Saakashvili's repeated hyperbolic declarations to satellite news stations, have obscured both the United States' culpability in bringing about the conflict, and the nature of the separatism that caused it in the first place. (Among other assertions, Saakashvili has called Russia's response to Georgia's assault on South Ossetia "a direct challenge for the whole world," and has said, "tomorrow Russian tanks might reach any European capital . . . [the war] is not really about Georgia but in a certain sense it's also an aggression against America".)

The United States started cozying up to Georgia before Saakashvili's time, during the ultra-corrupt presidency of Eduard Shevardnadze. At Georgia's request, in 2002 the U.S. began training, equipping, and modernizing the Georgian military for counterterrorism operations. It was a reasonable course of action in the wake of 9/11, and it especially made sense in view of the Baku-Supsa pipeline and plans to build the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline - the sole energy conduits to bypass Russia, thereby lessening the Kremlin's potential stranglehold over gas and oil exports from Central Asia to the West. But rigged elections for the Georgian parliament in November of 2002 incited widespread demonstrations. With backing and direction from American NGOs, and possibly guidance from U.S. ambassador Richard Miles (the former chief of mission in Belgrade who had helped the Yugoslav opposition peacefully topple Milosevic), the Georgian opposition carried out the Rose Revolution, unseating Shevardnadze and eventually resulting in the instatement of the charismatic pro-American Saakashvili.

Once in office, Saakashvili quickly sought to ally his country with the West, voicing aspirations to join the European Union and NATO. The Bush administration, flush with enthusiasm for promoting democracy after "liberating" Iraq, and certainly aware of Georgia's role as transit arena for the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline, was receptive. President Bush visited Tbilisi in 2005 and declared Georgia "a beacon of liberty," even as troublesome signs of Saakashvili's authoritarian streak were coming to light. The Georgian opposition has levied charges against Saakashvili of corruption and murder, and Western human rights groups, and even the State Department, have criticized him for the excessive use of force in suppressing demonstrations and restricting freedoms of the press, assembly, and political representation.

Soon Bush began promoting a third round of expansion for NATO and supported Georgia's ambitions to join. (Two previous rounds, in 1999 and 2002, proceeded over strong Russian objections, and had encompassed the Baltic states and erstwhile Soviet satellite countries in Eastern Europe.) In April of 2007 President Bush signed into law the NATO Freedom Consolidation Act, which advocates, and allocates funding for, the accession to NATO of the former Soviet republics of Georgia and Ukraine (as well as Albania, Croatia, and Macedonia). The pledge of mutual defense enshrined in the North Atlantic Treaty declares that, "an armed attack against one [member] . . . shall be considered an attack against . . . all." It was a protection Saakashvili hoped to avail himself of so as to free Georgia from the sphere of influence Putin was reasserting for Russia in former Soviet domains. Despite the fury to which the subject provoked Putin, the Bush administration lavished praise on Saakashvili and set about lobbying other NATO member states on his behalf, with mixed success.

The mere possibility that Georgia and Ukraine might join NATO prompted Russia to start flexing its military muscles and prepare for confrontation with Saakashvili and the West. In July of 2007 Russia suspended its participation in the Treaty of Conventional Forces, a landmark security accord of the post-Cold-War era. Apparently as a warning to Tbilisi, in August of that year a Russian aircraft fired a missile (which did not explode) onto Georgian territory. Clashes between Georgia and separatist militias in South Ossetia and Abkhazia increased; and although Saakashvili proposed autonomy to the two republics, he refused to rule out the use of force against them, scuppering the negotiations' chances of success. In September of 2007, Russia successfully tested what may be the world's most powerful conventional explosive device (dubbed Papa Vsekh Bomb, or the "Dad of All Bombs," by the Moscow media), a thermobaric, "air-delivered ordnance . . . comparable to a nuclear weapon in its efficiency and capability," in the words of a deputy chief of Russia's General Staff. Then, in a move reminiscent of the Cold War's grimmest days, Russian TU-95 long-range bombers resumed round-the-clock patrols that had ceased with the fall of the Soviet Union. These bombers have repeatedly veered toward NATO airspace, inciting alliance members Britain and Norway to scramble their fighter jets to intercept them. The bombers always retreat, but this, and a Soviet-style military parade - the first since the collapse of the USSR - held on Red Square this year, signal one thing: Russia is back.

Neither the Bush administration nor Saakashvili got the message. Germany, France, and Belgium, however, fearful of antagonizing Moscow even more, and especially concerned about Georgia's festering conflicts in South Ossetia and Abkhazia (stability and recognized borders are prerequisites for NATO membership) declined to endorse President Bush's initiative to bring Georgia into NATO. At the alliance summit in April of 2008, despite appeals from President Bush, NATO refused to offer Georgia a Membership Action Plan (the first step toward accession) and postponed the issue until the next summit in December. Under the auspices of the NATO Freedom Consolidation Act, the United States has nevertheless continued to finance the general upgrading of the country's military. About one hundred American military advisors were in Georgia when war broke out.

Emboldened by the prospect of membership in the world's most daunting military bloc, Georgia has had scant reason to compromise over the separatist regions. Were NATO to have admitted Georgia (the prospects seem dimmer than ever now) Georgia could have turned such disputes into casus belli between Moscow and the West. But that the United States would even consider proposing Georgia for membership in NATO reflects a blindness to the consequences of the first two rounds of NATO expansion and defies elementary strategic logic. Leaving aside how enrolling a tiny, technologically backward nation located in the remote Caucasus region jibes with NATO's treaty-adjured mission to "promote stability and well-being in the North Atlantic area," the next round could kill what remains of Russia's strategic cooperation with the West - cooperation the West will need, for example, to fight Islamic extremism in Central Asia, contain nuclear threats from Iran and North Korea, and control the proliferation of nuclear weapons. And Russia, with vast reserves of oil and gas, its arsenal of ICBMs, its million-strong conventional forces, its advanced arms industry, and its close relations with states like Iran, Syria, and North Korea, retains considerable capacity as a maker or breaker of international equilibrium. The West needs Russia on its side, much more than it could benefit from admitting Georgia to NATO, and even more than it would profit from the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan and Baku-Supsa pipelines. Moreover, NATO's previous encroachments into formerly Soviet terrain, in conjunction with NATO's 1999 war to prise Kosovo from Yugoslavia (an historic Russian ally and fellow Orthodox Christian nation) ignited in Russia the very anti-Western passions that have propelled nationalistic Vladimir Putin to sustained approval ratings of between 70 and 80 percent and threaten a new cold war. (When, in February of 2008, the United States recognized Kosovo's independence, Putin objected angrily, warning that a precedent was being set that would apply to South Ossetia and Abkhazia.)

Putin has strongly and repeatedly voiced objections to NATO's proposed expansion. Most notably, in February of 2007 he delivered an address in Munich that expressed a consensus - still valid - among the Russian political elite and people as a whole. After obliquely inveighing against the hegemonic pretensions of the United States, Putin called the upcoming enlargement an attempt "to impose new dividing lines and walls on us," and "a serious provocation that reduces the level of mutual trust." He need not be paranoid to discern in U.S. foreign policy evidence of hegemonic intent. The 2002 National Security Strategy declared that, "Our forces will be strong enough to dissuade potential adversaries in hopes of surpassing or equaling the power of the United States," and abandoned deterrence - the dominant peacekeeping principle of the Cold War. The Strategy issued in 2006 went further, proclaiming that, "It is the policy of the United States to seek and support democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world" - an implicit threat to Putin's autocratic regime, rendered all the more cogent by the "color revolutions" that American NGOs supported in Georgia, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan. The Bush administration's plans to station elements of a missile-defense shield in Eastern Europe have also poisoned relations with Moscow, especially since the shield could conceivably be deployed to shoot down Russian ICBMs after a first strike by the West. This is a strategically defensible apprehension in view of America's continuous upgrading of its nuclear arsenal and its drive to establish nuclear primacy, plus the ongoing decay of Russia's atomic weapons.

Since Saakashvili came to power, U.S. policy toward Georgia has been marked by ignorance of the Caucasus' history, and by aggressive assertion of lofty ideals divorced from realities on the ground. Whatever Saakashvili says about Georgia's relations with Russia now, the two countries share a deep history that complicates the present. Georgia, in fact, owes its very survival as a state to Russia. In 1783, the Georgian King Irakli II signed the Treaty of Georgiyevsk with Russia that would allow Russia to annex his country two decades later. The Georgians, wearied by Mongol, Ottoman, and Persian invasions, had for two centuries been pleading for Russian protection; to get it they were ready to surrender their sovereignty.

Georgia's problems with South Ossetia and Abkhazia stem from age-old internecine hatreds, accusations of massacres, and the two separatist regions' longstanding fears of what they regard as Georgian imperialism. Ethnically distinct from Georgians, the Ossetians are an ancient Iranian-Caucasian Christian people that the Mongol and Turkic invasions of the Middle Ages drove high into the rockbound barrens of Caucasus Mountains. Only Russian suzerainty over the region, established in the nineteenth century, allowed them to return to the fertile lowlands; whence the historical Ossetian amity toward Russia and view of Russia as something of a savior. Ossetia's division into North and South is artificial and stems from Joseph Stalin's tenure as commissar of nationalities in the 1920s, during which the future dictator drew the multiethnic Soviet Union's administrative boundaries in accordance with a policy of "unite-and-conquer," joining peoples with longstanding enmities into various "republics" and "autonomous zones" that would inevitably quarrel among themselves and therefore look to the Kremlin to keep the peace. Stalin (né Dzhugashvili), himself of Ossete and Georgian parents, split Ossetia, placing the southern half in Georgia (and giving it a measure of Soviet-style pseudo autonomy) and the northern half in Russia.

The peace collapsed with the dissolution of Kremlin rule in the region. In 1990, as the Soviet Union was crumbling, the South Ossetians declared independence from Georgia. In response, the Georgian leader at the time, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, abolished their autonomy. The South Ossetians then revolted against Tbilisi and ethnic Georgians fled South Ossetia en masse. Yeltsin brought about a cease-fire in 1992, under which Russia, with Georgia's consent, stationed troops in South Ossetia, ostensibly to keep the peace. Since then clocks in Tskhinvali have run on Moscow time; the ruble has served as the main currency; and Russia has granted citizenship to a majority. Saakashvili often vowed to impose his writ on South Ossetia, but the presence of Russian troops, to say nothing of the vehement anti-Georgian sentiments of the population, led to an often incendiary stand-off, with clashes occurring right up to the outbreak of the war.

To the west of South Ossetia lies the Republic of Abkhazia. Annexed by Russia in 1810, but joined to Georgia by - again - Stalin, Abkhazia is home to the virulently anti-Georgian, Abkhaz people, about one fifth of whom are Muslims who look to their (Muslim) brethren across the border in Russia for support. When the Soviet Union collapsed, Abkhaz separatists, aided by Russia, expelled Georgian troops from the republic, and a quarter-million ethnic Georgians fled with them. In 1994 Abkhazia declared independence (recognized by no one). Most Abkhaz are now Russian citizens. At least until the current war, CIS and UN peacekeepers patrolled the Abkhaz border with Georgia. Saakashvili pledged to recover Abkhazia, but UN-sponsored negotiations foundered, and no resolution has been in sight for a long time. Formally, at least, all sides - Georgia, Russia, the United States, and the European Union - recognized the sacrosanct nature of Georgia's borders - the same borders Stalin had drawn precisely in order to provoke the very conflicts that erupted in the Caucasus region with the fall of the Soviet Union and that we see unfolding now. The sole reasonable solution to the conflict - referenda in the two republics on independence, accession to Russia, or return to Georgian rule - has, so far, not figured in peace negotiations. Saakashvili opposed the idea in the past, and the Bush administration continues to insist on Georgia's territorial integrity - that is, on Stalin's borders. There is little doubt that now neither the Ossetes nor the Abkhaz would choose to rejoin Georgia.

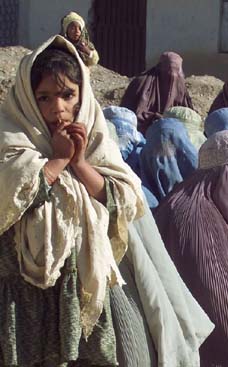

Perhaps Saakashvili believed that, with the world's eyes on the opening of the Olympic Games in Beijing, he could launch a lightning assault on South Ossetia and reclaim the republic without substantial grief from Moscow, as he had Ajaria in 2004. His statements once the war began demonstrated that he expected real Western help in confronting Russia. Whatever prompted him to miscalculate, the strategic realities ignored by the Bush administration in pumping up Saakashvili's ambitions reasserted themselves as soon as Moscow responded to Saakashvili's gambit with the largest military assault, by land, sea, and air since the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979. Within days, Georgia lost both South Ossetia and Abkhazia to Russia, two thousand Georgians were dead, tens of thousands had been displaced, foreigners were being evacuated, and Gori and Tbilisi, their airports bombed, appeared threatened.

As Russian bombs rained down on Georgia and Saakashvili pleaded for help from the West and for a cease-fire from Moscow, Putin stated bluntly that "Georgia's aspiration to join NATO . . . is driven by its attempt to drag other nations and peoples into its bloody adventures," and warned that, "the territorial integrity of Georgia has suffered a fatal blow." The Bush administration answered with boilerplate language of protest, failing even to dispatch Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice to the region until six days later for rounds of shuttle diplomacy. Saakashvili complained that "all we got so far are just words, statements, moral support, humanitarian aid." But neither the United States nor Europe will risk Armageddon for Georgia. For Saakashvili, game over.

The United States has, for all intents and purposes, abandoned Saakashvili, the poster-boy of the color revolutions, and left him at the mercy of Putin, who appears bent on exacting revenge. Moscow and the separatist leaders in both republics have pledged to charge Saakashvili in the Hague for genocide. The lessons that emerge from the Russia-Georgia war are clear: Russia is back, the West fears Russia as much as it needs it, and those who act on other assumptions are in for a rude, perhaps violent, awakening.

The historically volatile Georgians overthrew their two previous democratically elected leaders for much less than humiliation at Russia's hands and what will be the permanent loss of their two coveted wayward regions. Bitter notes of resignation and reproach toward the West are already creeping into Saakashvili's public pronouncements. "I have staked my country's fate on the West's rhetoric about democracy and liberty," he wrote in an op-ed piece for the Washington Post. He will take little comfort in remembering that the Bush administration, in adopting the outlandishly unrealistic National Security Strategy of 2006, did the same.