2011.10.22: October 22, 2011: Former Uganda Country Director J. Larry Brown writes: Peace Corps Washington

Peace Corps Online:

Directory:

Uganda:

Peace Corps Uganda :

Peace Corps Uganda: Newest Stories:

2011.10.22: October 22, 2011: Former Uganda Country Director J. Larry Brown writes: Peace Corps Washington

Former Uganda Country Director J. Larry Brown writes: Peace Corps Washington

"Peace Corps lore is that in any Peace Corps country, the Country Director rules the roost. He runs an outpost thousands of miles away, often two to three days flying distance, and culturally light years away. While I, as Country Director, supposedly had programmatic and financial authority at post, Washington monitored and controlled everything. Young hires in Washington would check the accuracy of our monthly cash count, verify the legitimacy of in-country travel I had authorized, and require HQ sign-off on all hiring done at post. Washington even required me, along with all my staff, to sign in and out of work each day, and then to submit weekly timesheets, practices I had never been forced to follow in forty years of previous employment. Always we were monitored, and always we had to jump and then wait. Washington's demand late on a Friday afternoon, for example, meant working that evening or the weekend, but when we needed a decision from HQ, we often waited weeks, and sometimes forever. Our needs often were ignored. Like the volunteers who felt treated like children, those of us supposedly in charge of each country post found that we had insufficient latitude to mold and shape it as we believed it should be. Washington ultimately decided everything, a clear case of the tail wagging the dog."

Former Uganda Country Director J. Larry Brown writes: Peace Corps Washington

Peace Corps Washington

by J. Larry Brown

Caption: The board room on the 8th floor of Peace Corps Headquarters in Washington, DC where the Peace Corps Director presides over meetings with his senior staff making decisions that affect countries of service all over the world. Photo: Hugh Pickens

Peace Corps lore is that in any Peace Corps country, the Country Director rules the roost. He runs an outpost thousands of miles away, often two to three days flying distance, and culturally light years away. Into this imposing situation the Peace Corps sends a Country Director who is supposed to make everything happen. So off I had marched with the best of intentions, into this challenging wilderness, but only to find out that from Washington's point of view we were the figures at the bottom of the puppet strings. The fingers of Washington reached into every aspect of my work. Like the volunteers who felt treated like children, those of us supposedly in charge of each country post found that we had insufficient latitude to mold and shape it as we believed it should be. Washington ultimately decided everything, a clear case of the tail wagging the dog.

The Washington bureaucracy, probably like all Washington agencies, has a myriad of offices designed to insure, assure, inspect, delegate and even dictate. Most of them are manned by civil service or foreign service people who meant well and wanted to do their jobs well. But governmental employees almost always fear doing something wrong or letting something go wrong on their watch. This fear, in turns, leads to rigidness, often times distrust, and almost always people taking their jobs far too seriously in the narrowest, most overbearing sense.

The fear and rigidity was manifest in a highly bureaucratic and controlling sense when Washington interacted with those of us running the posts. HQ informed us that we were being sent budget and planning guidelines tomorrow to cover our next three years, and they were to be completed and returned to Washington at a set date for HQ review. Our plans would then be sent back to us for revision based on Headquarters' comments. We were then told to re-write and return the documents in final form in ten days so HQ could decide how much money and how many volunteers we would receive in the coming year.

The pervasive bureaucratic requirements always were in force. While I, as Country Director, supposedly had programmatic and financial authority at post, Washington monitored and controlled everything. Young hires in Washington would check the accuracy of our monthly cash count, verify the legitimacy of in-country travel I had authorized, and require HQ sign-off on all hiring done at post. Washington even required me, along with all my staff, to sign in and out of work each day, and then to submit weekly timesheets, practices I had never been forced to follow in forty years of previous employment. Always we were monitored, and always we had to jump and then wait. Washington's demand late on a Friday afternoon, for example, meant working that evening or the weekend, but when we needed a decision from HQ, we often waited weeks, and sometimes forever. Our needs often were ignored.

Unfortunately, these practices represented only the typical marionette string control from Washington. Sometimes it got much worse. Every so often the Inspector General would come from D.C. to spend a week or two poring through the files and records in our offices. Each government agency has an IG office, and all its employees report to Congress on compliance with existing policies. The IG's job literally was to find anything and everything that did not represent flawlessness. During an IG audit, the staff was petrified, not only having to take time to assist the IG, thereby taking precious time from their other duties, but also standing in fear that the IG's findings of multiple small violations of policy would cover their own areas of responsibility. At the same time, the IG inspector were motivated to find as much imperfection as possible, because it justified his job, salary and continued ability to travel from country to country in an obviously futile effort to insure organizational perfection.

While IG inspections thankfully were not frequent, the long arm of the General Counsel's office was usually more of a presence. Out of the blue in only my fifth week at post, I was notified by the GC (General Counsel) that I needed to submit my ethics disclosure form for 2008. Glancing at the forms and instructions that poured from my printer as I ran off the attachments, I noted that I was to report every financial investment I had ever made and still held, including routine things like university retirement accounts, our daughter's college savings account, and even the earnings and investments of my wife who was not a government employee. Struck by the onerous and intrusiveness of the "request", I emailed the GC to ask for clarification. On the instruction forms it noted that the report was to be completed by all people who had been at post sixty days or more in 2008. But my wife, daughter and I had not arrived in Uganda until early January, 2009, only thirty-five days before.

It turned out that the GC's order for me to complete these forms was in error, but no apology was forthcoming. It was a good lesson for me: the GC's office existed to make sure that we made no errors, but it maintained the right to make even reckless ones. In my return email, I said that while I would submit whatever was required of me in the future, I was not sure that my wife would submit her own financial disclosure information since she had never been a government employee.

My message resulted in the receipt of a lengthy missive full of legalese, and without the usual first name greeting but addressed to "Dr. Brown…" And it was not from the attorney who had first contacted me but from the General Counsel himself. I was dressed down for being only the second person in his 20+ years of government ethics work who had "refused" to complete a required form, and I was notified that my failure to do so could lead to a highly serious outcome. Trying to figure out a way to pursue my questions without responding in kind, I sent back a "Dear Carl…" email that suggested we are colleagues and should work on matters together, even possibly waiting until the next year when the matter was ripe before discussing it. I also noted that in his memo to me, he stated that I would have to give my wife's financial information to Peace Corps, whether she was a government employee or not. Yet I found a clause stating that if I did not know about or control her income I was not required to report it. My subsequent query back to the GC led him to notify me that the matter was now so complicated that he and his staff would review it and get back to me. Whatever the outcome of this "review", the implications was clear: Washington was in charge and I, in Africa, was the marionette who would jump up and down when told to move.

The hyperactive GC was not the real culprit, but only one of many ethics officers in every government agency that annually require government employees to bare their hearts and souls, particularly their pocketbooks, to prove that they had not done something illegal. This bizarre, overly-intrusive and bureaucratic nightmare stemmed from as far back as Nixon and Watergate, and is part of Washington's over-reaction to virtually every expose. Integrity, common sense and innocent-until-proven-guilty are not the hallmarks of government any more. The rule now is control: show me, prove it, display it, tell all… even about your personal lives. I was now caught up in this snare.

The irony for me was not to see how government tried to implement transparency and reform that I supported in principle, particularly ethics-related reporting, but to see how rigidly and foolishly the principle was applied. In order to determine that I and other relatively lower-level employees were "ethics clean" they relied on my completion of this pro forma report. It did not require me to list amounts of income or the total of my investments, only the sources. And this under-reach was countered by the over-reach of requiring that the report cover my wife's income. To top it all off, most of the time the annual ethics forms are filled out by the employee, received by the agency ethics officer, and filed away. Period. Meanwhile, the big guys abusing government and the public either file nothing or get their attorneys to obfuscate in their required reporting. Like many Americans I had watched as our government had fallen into this morass over the years. Little had I expected, however naively, that the tentacles of the bureaucracy would follow me to Africa and reach so intrusively into my life running a post in Uganda.

This is how I felt after my first round with the General Counsel, but then a second volley was sent my way. Nancy Miller, an attorney in that office, informed me that while I did not have to fill out the report for 2008, I did have to complete the form for the last three months of 2008 because I was hired in late September. Go figure: I had to report on three months of the year but not twelve. Had I only known, I could have planned all sorts of unethical behavior for the nine months because I was not required to tell about it. I replied that I would complete the form and then noted, for clarification, a couple of things I apparently did not need to do because the GC's office had been in error. Her "school marmish" response read: "Larry, we are not going to get into a dispute about whether errors may have occurred(...)" Clearly her office had made errors, but my effort to confirm them so I could be clear about what I needed to do and did not need do appeared to be too much. The legal office that spent its time telling employees what was right to do and wrong to do could not acknowledge simple errors.

But it still was not over. I completed the ethics reporting form on the same day that I had to submit our Post's three year Strategic Plan to Washington. I should not even have been thinking about the ethics form because of the month-long Strategic Plan workload we were trying to finish, one requiring almost daily meetings and analyses with my staff, yet I succumbed to the pressure from General Counsel. As I completed the ethics document, I noted several things in the accompanying instructions. One was that it could be emailed rather than posted, because the federal government has an electronic signature security system. It was somewhat laborious to apply for and get access on-line, but I did so. The other thing was that in the section where I was supposed to report on all the sources of family income the previous year, the form clearly stated that "you may want to place an S for spouse or D for dependant in front of each income source." Knowing the precision of lawyer-speak, and being aware of the difference in meaning before the words may and must, I exercised my option not to make these notations. I was careful to follow all directions that accompanied the form as well, and I sent it in. When I reached the office the next morning, sure enough Nancy Miller jumped from my screen to greet me. She informed me that the OGE (which I intuited must mean Office of Governmental Ethics) would not accept an electronic signature, even though it was their form that I had completed-and which contained explicit instructions about how to "sign" a document electronically. Miller also informed me that I must note which sources of income were for me, my wife and daughter.

I saw that this would never end. For some reason, perhaps because I had suggested that their original errors were errors, I had become her target. She would be in my knickers forever. Perish the thought! I wrote her back to say that I had followed the ethics form instructions carefully and correctly. If their office had erred in the directions they sent me, they needed to correct them for all government employees, not just me. I was done responding to her ad hoc demands.

While I waited for the next shoe to drop from the Office of General Counsel, I was presented with bureaucratic over-reach in yet another part of Peace Corps Washington. Many posts had small grant money for which volunteers and their communities can apply to promote local development: establishing a community garden, building a henhouse for eggs to eat or to sell, or digging a simple well or sand filtration system for clean water. Among these small grants, usually around $1,500 to $5,000, are so-called Fast Track grants-grants for under $500 which were needed urgently. Applications for those grants were submitted by volunteers and screened by a committee of my staff and volunteers, and then given, along with a recommendation, to me for action. Because of their timely nature and low budgets, (often $150 or $175 for an entire village project), we turned them around in a week. A volunteer and her village got a response quickly, and the funding to act. In other words, it was possible for the bureaucracy to run smoothly and efficiently, particularly to help a village implement a vital project.

Suddenly I found myself copied on an email exchange between a relatively low-level bureaucrat in Washington and the Peace Corps Administrative Officer in Ghana. Said bureaucrat noted that posts typically issue Fast Track grants to the volunteer in cash, but that this is not authorized. Treasury regulations, she claimed, prohibit this. Instead, the proposals approved at post must be sent back to Washington where an electronic transfer would be made and deposited in a bank account for the volunteer to access in the future. I contemplated it: The Peace Corps volunteer who worked in a village without electricity and running water, and often without cell phone service, would have to wait for weeks for his "fast" grant to be processed in Washington, and then, assuming he got an approval, go to the nearest bank to pick up $175 for her chicken wire and nails.

A certain logic exists behind the Treasury regulations: cash is more easily lost or stolen than funds deposited in a bank. So Treasury required bank transactions. Except, it turned out, this was not what the Treasury said. The pertinent rule indicated that it was preferred that Peace Corps posts pay grants through this process, but that it was up to the discretion of the Country Director. Yet when the officer in Ghana pointed this out to Washington, they would not back down. Yes, a CD could authorize payment in individual cases, but not generally, or so we were told.

Trying to find a way out of another hard spot, I asked my staff about it. I learned that if a volunteer knows her grant money has been approved, she could come to Kampala, the capital city where the Peace Corps Office resided, sign forms and pick up the cash from our Cashier. Then volunteers can rush back to the village with the equivalent of $175 in cash and notify the waiting women's cooperative that their project work can begin. But, and this one floored me, if the approved grant information was sent to Washington for eventual payment to the, it typically took three weeks-three times longer than it did to evaluate and approve the grant at post. If there was a slip-up, it could take well over a month, even longer. This is how Washington wanted to make us handle our "Fast Track" grants. The very idea undermined the purposes of these expedited small grants.

I am not one who believes that people in government sit there to make life difficult for others, although sometimes this may happen and it almost always is easy to think it is the case. But it takes us back to the fear factor I mentioned earlier. Our government has become so over-regulated (at least in the wrong, everyday places) that well-meaning employees are scared to death of making a mistake. "No" has become far more easy to say than "yes".

In the case of the Treasury regulations it probably happened as a well-meaning action. A volunteer somewhere probably came to get the funds for the village project and either lost the money or had it stolen on the way back to the village. Peace Corps then had to cough up another $250 for the project and the birth of a new rule was in place. In order to guard against this one-time, low-probability problem from happening again, the bureaucratic mind went, let's make a rule so it cannot happen. The rule: except in emergencies, Fast Track grant must go to Washington where they may-repeat, may-be disbursed to the volunteer in three weeks.

The low-likelihood problem had been solved by the bureaucracy. Meanwhile, were I or other directors to follow this rigid rule, we would substantially undermine the capacity of our volunteers to carry out projects in a timely way. Got a goat project that could fall flat if the animals are not inoculated? Wait about a month. Got a community garden plot ready to go before the rains end. We may ship the money to you on time, or we may not. Got a clean water project to keep kids from getting cholera? Hope they can last another month drinking the dirty run-off. To the bureaucrat sitting at a desk in Washington, procedures seem so tidy and logical. All that needed to happen was for the villagers to wait for the processes of government to unfold. And, oh yes, it would help if that volunteer had submitted his proposal several weeks ago to allow for Washington's slowness. That volunteer has his own constraints, and they are far more legitimate than the bureaucrat's. He (or she) lived fourteen kilometers from the nearest city from which they can post or email their grant proposal. The village was intent on getting its crops planted before its members could meet to finalize their chicken coop project. And the chicken project chairwoman was tending to her sister in the next village whose baby had just died in childbirth. Meanwhile, the volunteer was trying to bring it all together to have an impact on the lives he was trying to save, and then figure out how to send in the proposal from his dusty location eight thousand miles from Washington-totally innocent of the fact that some D.C. rule might undermine all he had done and all that the villagers dreamed of doing.

Despite Washington's strong hand, I was committed to running the post as well as I could, and a key to this was to make sure my Ugandan staff were full participants in all the processes, bureaucratic or not. I had taken the entire staff through the strategic planning process, an annual, three-year submission which was the way a post asks Washington for volunteers and budget support. None of my staff had ever before been involved in this process, not because they were not around but because they had not been asked. My predecessor wrote and submitted the plan herself. This time, over a thirty-day period, I involved every member of the staff, including the drivers and the custodian. We had eleven meetings, an afternoon retreat at our house, and shared documents, edits and production of a three-year plan. The staff was proud to have been involved and trusted in this collaborative process which, itself, was a microcosm of Peace Corps' mission to enfranchise people by promoting greater self-sufficiency. Moreover, I felt that we had nailed it: identifying what Uganda needed and what we could do to help the nation become more self-sufficient.

Our plan was submitted a day and a half before the deadline Washington had given Africa CDs to send in their plans. I was pleased with the efficiency of our planning process and noted to HQ that it had been a full-post effort. Even though I was a new CD and, I later learned, the first CD on the continent to submit his plan, my supervisor, Lynn Foden, never acknowledged my submission. Nor did any of the other formal recipients; it was as if our hard work simply had vanished into thin air.

Our next guidance from Washington arrived via email on a Monday. "Guidance" is how Peace Corps refers to the demands it places on each post in the world. The term clearly was preferable to "burden" or "requirement" but it still sounds (and felt) paternalistic: here we sat, the country directors waiting for someone in the know to guide us about what we needed to do. The tendency was overpowering, even for relatively young and inexperienced HQ staff, to assume that they had superior knowledge, even 8,000 miles from the scene of action.

While we were guided daily from Washington, this time the orders arrived in the form of directives to tell us when and how to do our mid-year budget reviews. The reviews actually were a very legitimate idea, an analysis of how much each post said it would spend by budget item, how much it actually spent, and its desired reallocations and projections for the remainder of the year. But somehow the bureaucracy never seemed able to make things quite this simple.

The first thing I noticed was that the guidance given to us, to complete three budget documents, totaled ten pages. This set of instructions was not just ten pages, but ten single-spaced pages. And it was not just the detail that hit me but the fact that the directions told us every single thing to count, report, do and even say. Even the cover letter that I and other CDs were to submit was prescribed by Washington: cover this, include that, address this, explain that.

For all the thought that no doubt had been devoted to guiding us, the lengthy guiding missive was a mess. Someone or ones had taken the template for mid-year budget directions from the previous year and edited it to death. They had made tracked changes all over the document, but then had forgotten to hit "accept" in the final version before the document was emailed to us. Hence, the document distributed to CDs all over Africa contained both the edited and unedited versions, with all the changes that had been red-tracked in the text of our guidance.

I smiled when I thought about the likely response from HQ were we to submit something so sloppy to our guiders in Washington. What if a post were to send in something so hard to wade through, a document that even required manipulation and clean-up in order to be deciphered and used? Then I saw something I had at first missed. Our guiders had given us just ten days to conduct this budget review. From start to finish, we were to read, decipher, clean-up and follow the instructions all in ten days (actually seven and a half work days if we did not work on the weekends, although many of us did).

This timetable may not sound so terrible if one assumes that we had nothing else to do but feed the Washington bureaucracy. But in Uganda, we had a few other responsibilities at the time, mandatory tasks that we had been guided to do by yet other guidance directives that had sent out by Washington. We were in the midst of the laborious task of processing the close of service for about fifty-five volunteers, who were completing their two year terms. Each one had to be interviewed individually, twice in fact, once by their manager and once by me, a total of one hundred and ten hours of interviews somehow squeezed into our other responsibilities. In addition, we had thirty new volunteers who had just completed their two months of intensive training. They were at our headquarters in Kampala for three days for their own interviews, dinner at our home, and a formal full-morning swearing-in ceremony (dignitary speeches included) before departing for the villages where they were to be placed.

In addition, we had a third group of volunteers in Kampala for a week-long conference on life-skills training, to help PCVs better impart discipline and other life skills to Ugandan youth who had been raised in non- supportive circumstances.

Preparation and execution of this conference took several staff members, who also needed to be present when it happened because the co-workers of each of the volunteers had come in to participate as well. And I, as well as other staff, periodically needed to be driven out to the training site to participate.

The last of the four different volunteers groups at post was coming in the next week for what was called Mid-Service, the training regimen that all PCVs receive when they are half way through their tour of service. This, too, took a great deal of staff planning and preparation. It also meant that our entire volunteer community of 165 people was moving in and out of headquarters, each with their own needs, and each needing the support of a heavily overworked staff. On top of all this, my staff and I were trying to fulfill our other responsibilities: addressing volunteer emergencies; traveling to meet organizational leaders with whom we might be placing future volunteers; meeting with USAID and international NGOs to check out other possible sites; tracking petty crimes against staff and volunteers; and reading and analyzing site reports and close of service reports. Despite these burdens, we also were significantly short-staffed due to staff lost due to HQ budget cuts at the start of the fiscal year, before I had arrived.

At the end of this latest guidance, telling us to complete the mid-year budget review and return it to Washington within ten days, our other responsibilities notwithstanding, was a notation whose significance was hard to overlook: "The completed mid-year review is due on April 24, and decisions (by Headquarters) will be communicated to you in early June." In other words, we were given ten days to prepare and provide our budget analyses, even in the midst of all that was going on at post, but Washington retained the right to take six weeks or more to respond to us after that, clearly giving no date certain by which it would do so. Always posts-and we CDs who tried to run them-operated at the whim of HQ: things Washington needed were due "now," while what we needed from HQ never had a deadline. We simply were expected to wait… the dangling puppets at the end of the string.

We got our budget materials, along with the prescribed cover letter, in to Washington on time, timely enough that we then were able to go back to our daily responsibilities of running a sizeable post. But it did not leave a warm and fuzzy feeling that we had been so-guided from afar. My only solace was the recognition that the persons guiding us were simply trying to do their jobs. After all, they, too, had handlers in still other federal agencies who were guiding them to do what they did to us.

My magnanimity in understanding their plight, however, lasted only through the weekend, both days of which I spent in my office to catch up on regular responsibilities I had set aside to meet headquarters demands. By the time I reached my desk mid-morning that Monday, following three early meetings at the American Embassy, it became clear that Washington's insatiable demand for immediate responses to spontaneous tasks was almost boundless. Within the next forty-eight hours the demanding emails poured in regularly, all in the midst of my staff and me trying to conduct the required exit interviews with our volunteers leaving service, tending to the new group of volunteers placed at their sites for the first time the previous week, simultaneously running a Mid-Service conference for another group with a year still to serve, and finding appropriate work placements for four dozen new volunteers who would be arriving in several months.

A mere forty-eight hours after we'd completed the mid-year review process, we had four new directives to complete and submit to Washington, all on extraordinarily tight deadlines (see appendix 1). Notably, these directives were not aimed at some errant post. They were directed either to all Peace Corps Country Directors or, at minimum, to Africa CDs. Overwhelmed with the continuing barrage, I found two new emails from Nancy Miller in the General Counsel's office. I had been right: her sharp hooks were in me and I had no reason to expect that I could get them removed short of death, although whether hers or mine seemed an interesting consideration.

To her credit, she finally responded to my request for copies of the communications she and the Office of Governmental Ethics had exchanged about me. However, instead of simply sharing the communication with me as members of the same small federal agency, she had decided to treat my request as one made under the federal Freedom of Information Act. The results were the same, namely that I received their communications, but because of the unnecessarily formal, legalistic process she elected to follow, I also had to wade through all the lawyerly verbiage as well. Notably, however, Miller completely failed to answer my question about why they had instructed me to file an electronic signature if they did not accept that form of verification. Neither was she able to provide a reason for demanding that I add more detail to the family income portion of the form than was required. She reiterated her demand that I comply with both of the new requirements that she had placed on me weeks before.

I then found the heavy artillery lurking in some formerly off-record exchanges Miller had had about me with the Office of Governmental Ethics. In their back and forth emails, the OGE representative, someone who had never met or spoken with me, had referred to me as the "recalcitrant" individual. I cringed and then smiled. Since the term refers to one who is resistant to domination, I had to give the OGE writer her due: that sounded like me. Certainly, in this case, I had asked questions that led these paper-shufflers to conclude that I resisted their orders. But when I got sufficient responses to my queries, and then completed and sent in the ethics form, I was no longer resistant. By definition, I was compliant. But even that was not enough.

My eyes focused on a line in their exchange that opened the door to criminalizing my actions in filling out the ethics form. It read, "You can consider 18 USC sections 1001 and 1018 if he chooses to knowingly provide false information. Otherwise, your enforcement tools are exclusively administrative." In other words, OGE and the IG had decided that they might have an avenue to prosecute me for falsifying federally-required information. Rather than be shaken into kow-towing to their unilateral demands, demands tailored to me and not to all Peace Corps employees, I smiled at the self-centered audacity. I had done everything that the ethics reporting process required. I was honest, and I had nothing to hide. Yet because I was not easily bending to their every subsequent demand, I was now under suspicion-by my own agency colleagues. They might decide to accuse me of criminal behavior. Assuming that the codes of federal laws to which they referred carried the typical fines and jail sentences, at least I could assume that my next ethics report would be less complicated with respect to family income. Sitting in a jail cell, I'd have fewer forms to mail too Washington.

If Washington had only demanded numerous data and mountains of information in impossibly short periods of time, it would simply make running a post in a foreign land tediously miserable. And if the rhetoric about HQ existing to serve posts simply masked the reality that all demands emanate from Washington, and all decisions end there, it would simply lead to the stressful anger about which most country directors regularly commiserated. But fortunately the bureaucracy of Washington finds ways to entertain as well, and its mechanism of choice is to regularly engage in dumb deeds. With every Nancy Miller who seeks to move into your knickers, there seems to be one or two people in the bureaucracy who are too dim to think outside the box. Now comes the story of the "$4 bureaucratic dumb deed." The swearing-in of new volunteers always was an auspicious occasion at a Peace Corps post. Some country posts took in only one new group of volunteers each year, but most took in two. Because of the infrequency of these events, and because the swearing-in ceremony culminates a two to three month formal training program to equip volunteers to live and work in-country, it usually was a happy yet solemn event. It often was attended by current volunteers, supervisors and co-workers of the new ones being sworn in, by dignitaries such as the Ministers of Education, of Health, of Economic Development, and almost always by the United States Ambassador and representatives of other U.S. agencies.

This was my first swearing-in ceremony, and I wanted to get everything just right. After talking with Judi, we decided to host a dinner at our house for the new volunteers-to-be, the evening before their swearing-in ceremony. Altogether, the thirty of them, invited guests and staff, came to sixty persons who would be attending, so my staff made preparations to pitch two large tents in our beautifully manicured yard. That part, the tents, chairs, coolers and dishes, was the easy part since our post already owned these supplies. But in a government agency little else is ever easy.

In order to identify a caterer for the event, basically an entity to cook and serve the food, and to clean up afterwards, we were required to put out bids and then select the best deal from amidst the three or four who sent quotes. This we dutifully did, not only abiding by the rules of Washington but also trying to save every dollar for an event that would cost under $500 altogether, quite a deal for entertaining sixty people. The price could have gone much higher but we decided to have the caterer serve buffet style rather than individual table servings.

Had we gone with individual servings the bureaucracy would have permitted it. But we cut overall costs by $1,000 by serving buffet style. We also found a way to save even more money. Had I decided to hold the dinner at a site fifteen kilometers from the office, I could have put all staff and volunteers on travel status, thereby making them eligible not only for several meals but overnight hotel accommodations as well. Deeming this possibility both unnecessary and wasteful, I decided instead on the relatively small and informal meal at our house. Everyone arrived around seven and all were gone by about 10:30, after enjoying an evening of food, fun and minimal entertainment. All had gone well, our first such event being simple and successful. The trouble from Washington, however, was to begin later in the week.

Even though posts have their own financial analysts and budget officers, every fiscal transaction we made had to be reported to and approved by Washington. In other words, Peace Corps Washington required us to have sufficient staff in-country to follow U.S. rules and regulations relating to the authorization of financial obligations, receipt and validation of all the documents to insure accuracy, and to pay and record them once finally approved. But instead of relying on the American-led team on the ground (in this case Uganda) to follow these established procedures, we then had to send all records to Washington so teams of people at Headquarters could do it all over again. Not only was this process redundant and time-consuming, but it applied the same to the purchase of a pencil as it did to hiring an airline to medically evacuate a dying volunteer.

Shortly after my financial staff had approved payment for the dinner at our home for the new volunteers, sending all bills and requisite information to Washington, we were notified that what we had done was inappropriate. Washington wanted a list of the names of all people in attendance so it could verify that each of them deserved the $4 buffet-style meal of rice, salad and chicken. Moreover, we were to indicate which of the names on the list were new Peace Corps Volunteers (to be sworn in the next day) and which were other people, who they were and what organization they represented. Headquarters also instructed us to inform which, if any, of our staff were on travel status, thereby possibly making them eligible (or ineligible) for the evening meal. Finally, I got my come-uppance as the new CD trying to do the right thing for his new volunteers: reimbursement for my own dinner was disallowed. My $4 meal would have to be paid directly by me.

The somewhat-understandable rationale on the part of Washington is that staff receive salaries that should cover their living expenses, so reimbursing us for an extra meal like this amounted to a back-door pay raise. In order to avoid such abuse, in this case the $4 for my meal, Washington was willing to spend hundreds and hundreds of dollars in time and, therefore, D.C. salaries to ferret out such errors. One could easily conclude that this is the essence of "penny-wise and pound-foolish" bureaucracy, examples of which drive the public to apoplexy, and create a near-total lack of faith in the intelligence of bureaucracy.

My administrative officer forwarded the HQ email about our errors on to me, no doubt with a smile on his face in anticipation of my response. I wrote to the sender from HQ, noting that I was a relatively new CD and still had a lot to learn, after which I asked for clarifications regarding her concerns:

The event was a self-service buffet, so individual meals were not served. If I did not eat are we still to pay for my portion?

What were we to do with the leftovers from the buffet? Is it OK to give them to attendees or would that increase their proportionate share?

Do we need to somehow account for people who came back for seconds? I didn't think to keep a list of them at the time.

Some leftover rice ended up in our fridge. Without thinking my wife ate it the next day. Should we pay for a second meal for her? Otherwise, we could get a bill from the vendor to verify the price for a half cup of rice.

I ended my brief revenge by noting that had I chosen to, I could have held the event away, put everyone on travel status, and made the government spend about a thousand dollars more than our modest shared meal to honor new volunteers.

My note was never acknowledged. We did, however, get several other emails from the same bureaucrat about the same set of issues until, after about two more weeks, the matter was settled in a manner that pleased Washington. My administrative officer and I tallied up the cost of the $4 meals for ourselves and other Peace Corps staff and paid them out of our own pockets. Clearly our angst was not over the twenty bucks each of us coughed up but, instead, the belittling fact that we had to spend all the time and trouble on such a numbingly dumb requirement. Meanwhile, I calculated that in order to prevent me from getting a free $4 meal that I didn't even have time to eat anyway, and to "catch" possibly others who might have been freeloading off the American government for their own $4 meals, the Peace Corps had spent between $800-1,200 in staff time on the part of both its Uganda-based and U.S. employees as we diddled back and forth over several $4 meals.

This type of silliness occurred over and over during my Peace Corps service. Several months later we convened an all volunteer conference, bringing together 137 volunteers currently for a rigorous knowledge- sharing conference on health and economic projects. Because of the importance of the event I asked a number of my senior staff to attend for most of the three-day meeting, a schedule so packed that even evening sessions had been planned. Only after making this request of them did I realize the problem I had caused. Because the conference was held in Kampala, rather than far enough away to place my staff on travel status, neither they nor I could dine with the volunteers each evening unless we paid for our own meals. Federal regulations would not permit us to partake of the buffet meals served to all since, it was reasoned, we could go home to eat, thus saving the government four dollars for each of our meals. But going home to eat would have cost the government far more. Because we were officially working up to meal time, and, then again, afterwards, until the conference closed each evening, each staff person could have had a driver and car ferry him or her to home and back. In petrol costs alone (then at over $5 a gallon in Uganda), let alone the costs of keeping all the drivers on an overtime payroll late into the evening, the total bill to the government would have been far more than four bucks a person.

Part of me wanted to succumb to the temptation: pay the ridiculous extra amount and then let Peace Corps Washington know how it had spent hundreds of dollars over the three days of the conference simply to avoid a few four dollar meals for staff. But no one would care and, even if they did, no one would try to do anything about it in the future. Instead, we did the only thing we could do. We paid for the staff meals out of our own pockets. I was sure that officials in the Pentagon were not doing the same for their staffs' much more luxurious meals, but this was Peace Corps and the bureaucracy was the bureaucracy. Penny wise and pound foolish, bureaucratic sticklers to the max, Headquarters ruled and we remained marionettes at the end of their strings. "We have come a long way since the days of Sargent Shriver," lamented my colleague, Mike McConnell, Country Director in the Gambia. Referring to JKF's first Peace Corps Director, Mike added: "Gone is much of the fervor… the bureaucracy has taken over everything we do."

Click this link to read Part II of "Peasants Come Last."

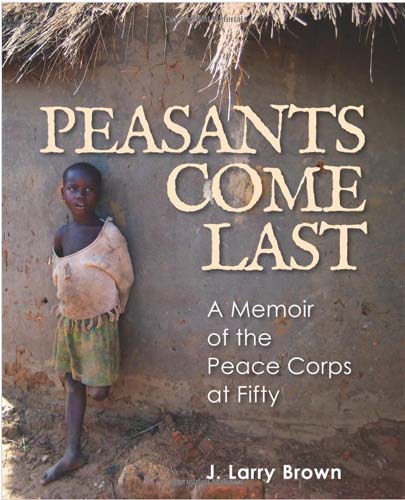

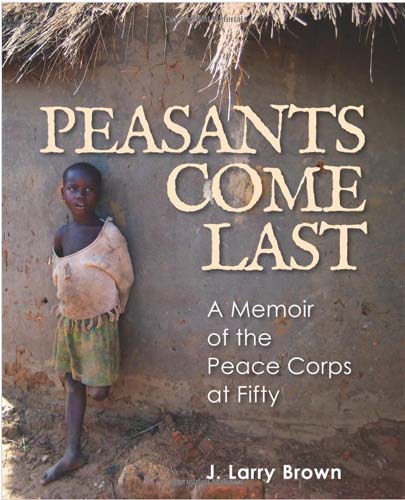

About the Book

In the tradition of popular activist scholars like Carl Sagan and Stephen Jay Gould, J. Larry Brown has spent decades linking the findings of science to the realities of human existence. He gives us a candid look at what it means to try to do good things in a harsh world. We are taken to the make-shift huts of refugees driven from their homes by the insane barbarism of the Lord's Resistance Army. We stand with Brown where Livingstone once stood, at Murchison Falls overlooking the powerful Nile filled with hippos and crocodiles. We see the grinding lives of people who eat the same meal every day. But of all the obstacles faced by Brown and his colleagues, none is as nonsensical as the tone-deaf dealings of Washington. We see how the needs of peasants come last when the realities of their lives are no match for the machinations of Washington's rigid routines.

Purchase the book at Amazon.

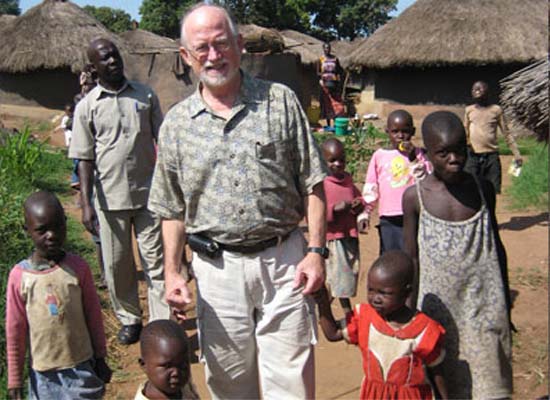

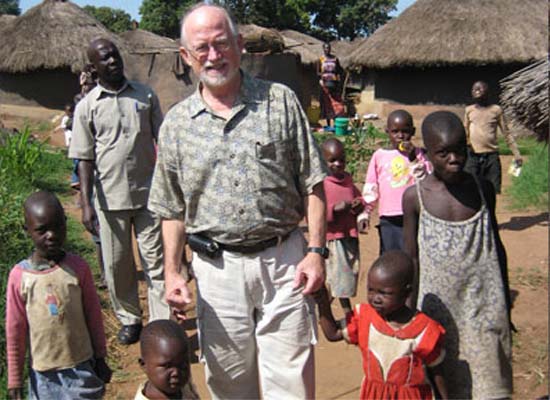

About the Author

Serving many years on the faculty of the Harvard School of Public Health, Dr. J. Larry Brown riveted national attention to the existence of hunger in America in the 1980's, when he led a team of prominent doctors on field investigations into twenty-five states. The founding director of the Center on Hunger and Poverty, Brown also founded the Feinstein Famine Center and the Institute on Assets and Social Policy. Dr. Brown chaired the board of Oxfam America, and also chaired the medical task force of USA for Africa and Hands Across America. He is the author of numerous articles in both lay and scientific journals, such as Scientific American and Encyclopedia Britannica, and several books including Living Hungry in America. He has appeared often on national television including CNN, Good Morning America, Today Show, and network news programs, and testifies frequently before Congress. A young Peace Corps Volunteer in rural India in the late 1960s, Brown later served under President Carter as Assistant Director of the Peace Corps. He recently served a stint as Country Director for the Peace Corps in Uganda, and now resides with his wife, Judi Garfinkel, in Oman, where they head programs for World Learning/SIT.

Links to Related Topics (Tags):

Headlines: October, 2011; Peace Corps Headquarters; Criticism; Country Directors - Uganda; Speaking Out; Peace Corps Uganda; Directory of Uganda RPCVs; Messages and Announcements for Uganda RPCVs

When this story was posted in October 2011, this was on the front page of PCOL:

Peace Corps Online The Independent News Forum serving Returned Peace Corps Volunteers

| Peace Corps: The Next Fifty Years

As we move into the Peace Corps' second fifty years, what single improvement would most benefit the mission of the Peace Corps? Read our op-ed about the creation of a private charitable non-profit corporation, independent of the US government, whose focus would be to provide support and funding for third goal activities. Returned Volunteers need President Obama to support the enabling legislation, already written and vetted, to create the Peace Corps Foundation. RPCVs will do the rest. |

| How Volunteers Remember Sarge

As the Peace Corps' Founding Director Sargent Shriver laid the foundations for the most lasting accomplishment of the Kennedy presidency. Shriver spoke to returned volunteers at the Peace Vigil at Lincoln Memorial in September, 2001 for the Peace Corps 40th. "The challenge I believe is simple - simple to express but difficult to fulfill. That challenge is expressed in these words: PCV's - stay as you are. Be servants of peace. Work at home as you have worked abroad. Humbly, persistently, intelligently. Weep with those who are sorrowful, Care for those who are sick. Serve your wives, serve your husbands, serve your families, serve your neighbors, serve your cities, serve the poor, join others who also serve," said Shriver. "Serve, Serve, Serve. That's the answer, that's the objective, that's the challenge." |

Read the stories and leave your comments.

Some postings on Peace Corps Online are provided to the individual members of this group without permission of the copyright owner for the non-profit purposes of criticism, comment, education, scholarship, and research under the "Fair Use" provisions of U.S. Government copyright laws and they may not be distributed further without permission of the copyright owner. Peace Corps Online does not vouch for the accuracy of the content of the postings, which is the sole responsibility of the copyright holder.

Story Source: Peace Corps Online

This story has been posted in the following forums: : Headlines; Headquarters; Criticism; Country Directors - Uganda; Speaking Out; COS - Uganda

PCOL47503

71