2011.10.22: October 22, 2011: Former Uganda Country Director J. Larry Brown writes: Peasants Come Last

Peace Corps Online:

Directory:

Uganda:

Peace Corps Uganda :

Peace Corps Uganda: Newest Stories:

2011.10.22: October 22, 2011: Former Uganda Country Director J. Larry Brown writes: Peasants Come Last

Former Uganda Country Director J. Larry Brown writes: Peasants Come Last

I had just completed some wonderful first months, was in love with my job, keen on the culture, and enthralled with the work of my volunteers in their villages. My volunteers had taken my challenge to "own" the post, and were now involved in all aspects of its operations. They served on all hiring committees, were members of the grants committee, oversaw the monthly newsletter, ran two of their own committees, and had accepted my challenge to plan the remodeling of their resource center and computer room. I now had the confidence of the staff as well, especially the Ugandans to whom I had given significantly greater management responsibilities. They told me of their pride in being part of Peace Corps and no longer seemed reticent to speak up both at staff meetings and in one-on-one discussions to help educate me. Everything was going swimmingly. Clearly it was time for my balloon to burst, but little did I know that it would be Peace Corps Washington that would do it. And I could never have guessed that I would watch bureaucratic indifference trample over the needs of Ugandan peasants. After all, this was Peace Corps, champion of the world's peasants.

Former Uganda Country Director J. Larry Brown writes: Peasants Come Last

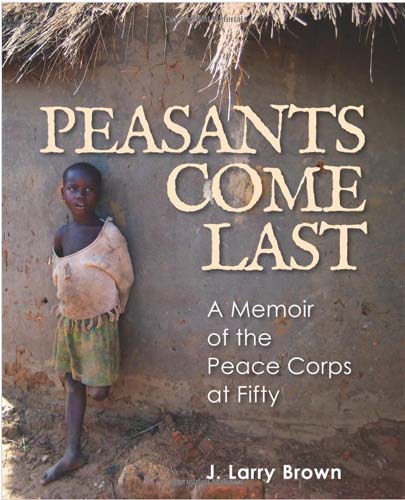

Peasants Come Last

by J. Larry Brown

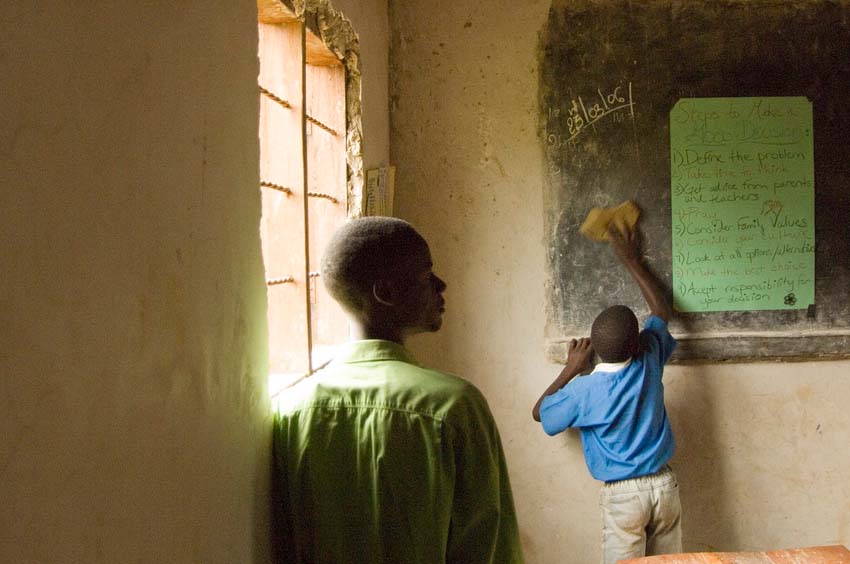

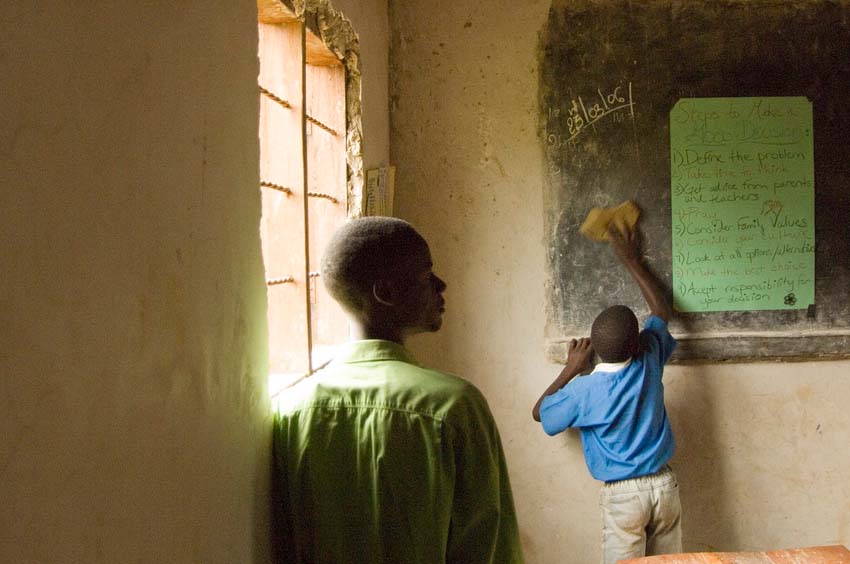

Photos of Peace Corps Uganda. Flickr Creative Commons. All Photos courtesy US Peace Corps.

The tenure of a Peace Corps County Director, like that of volunteers, runs in predictable cycles: first is a honeymoon of several months of excitement and novelty, then the realities of working in a third world environment set in, the frustrations and doubt mount, and the next several months range from melancholic to depressing. Nearing the first year mark, they learn to live with and negotiate the new culture, again feeling quite good about the experience.

I had just completed some wonderful first months, was in love with my job, keen on the culture, and enthralled with the work of my volunteers in their villages. My volunteers had taken my challenge to "own" the post, and were now involved in all aspects of its operations. They served on all hiring committees, were members of the grants committee, oversaw the monthly newsletter, ran two of their own committees, and had accepted my challenge to plan the remodeling of their resource center and computer room. I now had the confidence of the staff as well, especially the Ugandans to whom I had given significantly greater management responsibilities. They told me of their pride in being part of Peace Corps and no longer seemed reticent to speak up both at staff meetings and in one-on-one discussions to help educate me.

Everything was going swimmingly.

Clearly it was time for my balloon to burst, but little did I know that it would be Peace Corps Washington that would do it. And I could never have guessed that I would watch bureaucratic indifference trample over the needs of Ugandan peasants. After all, this was Peace Corps, champion of the world's peasants.

Volunteers come to the country in which they serve through a rather convoluted agency process: the types of skills that new volunteers need to possess are determined by the post in each country, and volunteers are then recruited in the U.S. Next they are assigned to country by categories of their specialties (agriculture, water, education) by the Placement Office at Headquarters. Finally, they come to their assigned country for eight to ten weeks of rigorous training, and finally and go to their village sites that have been identified and arranged by staff at post.

An outsider could almost predict the battles and tugs between the various constituencies in this process. Country Director: we need agriculture and education volunteers but Washington usually gives us generalists. Recruitment Unit: do the country directors think we are magic, how can we deliver all the skills you need? Placement Unit: we need orderliness, countries cannot change their minds after they decide what they need. Even though I once directed Peace Corp's national recruitment operations in the Carter Administration, and had some sense of the inside picture, I could not have imagined the lesson I was about to learn.

Riding my initial wave of euphoria, I had worked hard with other American programs in Uganda, especially USAID and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) to debate and formulate a plan assessing Uganda's primary needs and, therefore, our key priorities. It had all gone very smoothly, bureaucratic cooperation and mutual support with the strong blessing of Ambassador Steven Browning and the Deputy Chief of Mission, John Hoover. Government development work was working as it was supposed to work.

Our assessment of Uganda's needs was based on several key developments, the first being that Joseph Kony had now been driven from Uganda and was hiding his weakened forces in the jungles of the Congo. With Kony gone peasants now were "free" to return to their devastated former villages. But how? A full generation of children had grown up in these camps and they did not have the knowledge of cultivation and farming or the basic rudimentary skills to survive outside the sustaining but stifling womb of the camps for internally displaced persons. The people needed seeds, they needed wells, and they needed skills. These were the things that Peace Corps Volunteers could bring.

On another front, a full scale "food crisis" was brewing on the border between Uganda and Kenya. The isolated and desolate Karamoja District was home to traditional nomadic pastoralists. They lived off the land, follow their cattle from place to place and, depending on whether one is a romantic or realist, lived an idyllic or precarious existence. The colorful Karamojans, outcasts in their own country because of sharp tribal differences and cultural practices, also are highly vulnerable to man and nature. They robbed one another of cattle, they stole grazing spots and water holes, and they ate little when the rains did not provide the meager grains upon which they depend. According to the United Nations and the World Food Program, a food crisis was developing in Karamoja. Without immediate intervention, crop failures would lead to starvation. Here too, Peace Corps volunteers could play a key role.

On a third front, we had determined that small-scale micro-enterprise development was central to the needs of Ugandans in general. While HIV/AIDS command much attention in Uganda, infected people actually live shorter lives due to malnutrition and other diseases. AIDS rarely is the cause of death. HIV victims die instead of the conditions of poverty: dirty drinking water, malaria and tuberculosis. Increasing their livelihoods and well- being through micro-enterprise projects such as raising poultry, beekeeping, small animal husbandry and community gardens could sustain people, prevent untimely deaths, and build local economies. Not surprisingly, Peace Corps is very good at training volunteers to facilitate these activities on the local level.

In my first months representing Peace Corps, I had worked with other American agencies in Uganda to develop our analysis of need and our mutual responses. We were independent agencies but we were coordinated, in sync about the country's greatest needs. I proudly forwarded our country plan, setting out Peace Corps' niche and contribution, to HQ as requested. It was March, 2009, and I noted that for volunteers who would enter villages to serve as of April, 2010 (more than a year later), we desperately needed 17 economic development volunteers out of an anticipated new group totaling 37.

In addition to our plan to place volunteers with these highly-needed skills, I also asked Washington for what is bureaucratically known as unfunded requests, a term for restoring cuts they had made to post capacities earlier in the year. Now that Congress had passed a budget (six months into the fiscal year) and Peace Corps had been given an extra $18 million, posts could ask for the positions back that had been cut earlier. Given our post's growth and the needs I had chronicled, we needed two staff positions re-stored.

I heard nothing back from Washington, either about our program plan or our budget needs. Perhaps I was a bit needy to have hoped that key regional staff would have noted that Uganda was the first of twenty-six countries in Africa to submit its plan. Beyond that, however, I hoped they would note that the plan was well- reasoned, well-written and responsive to the needs of the villagers we had come to serve. And, of course, I thought my boss surely, Lynn Foden, would replace the staff that had been taken from us even as we had doubled our number of volunteers. Not on your life.

I waited several weeks before being informed that it was too late for me to ask Washington for economic development volunteers. Puzzled, I noted that our request was submitted in March, 2009, for volunteers to be placed more than a year later. How, I wondered, could it be that we had been too late! I then learned that I had missed a HQ deadline by a month. As a new Country Director, a deadline about which Washington had never informed me would now preclude all our planning to respond to the urgent needs of Ugandans-- in Karamoja, those coming out of the camps, and those in the war-ravaged north. No way did I intend to let that happen.

I sent a memo, explaining the entire situation to Lynn Foden, the Acting Regional Director. I still got no response. I sent a follow-up note to explain how our staffing request and program plans interrelated. And I put the entire analysis in terms of the needs of Ugandans, people whose average income is one dollar a day and whose average life expectancy is forty-nine years. Surely Foden would listen. After all, Headquarters says it is there to support the regions, the more than seventy Peace Corps country posts around the world. We lived on the front lines doing what President John F. Kennedy had asked us to do for our country.

Lynn Foden dug in. She finally informed me that it was not her, but the Placement Office, that would not let us make requests so "late" in the process (more than a year in advance). I tried to reach the Placement chief. Two unanswered emails later, I learned that Lynn Foden had told him not to speak with me. I called my desk officer to set up a time to speak with Foden. I was told a time that she would call me, and sat by my phone after our office in Uganda had closed for the day. The call never came. A mistake I was told, so the desk officer set up another time. On this occasion I sat for more than an hour waiting for the call. Nothing. I next learned that Foden was traveling for two weeks but would call me from the road. It never happened.

Finally I was able to arrange a phone call with Foden. I explained our situation and the need. Foden said that I couldn't just come at any time in the process to say I needed volunteers with certain backgrounds and skills. I pointed out that I was not asking for an iron-clad promise, only that in the next year they would try to deliver the kinds of volunteers we needed. Foden said I should lower my expectations for the 17 volunteers we needed, and to request more generalists, that is, recent college graduates with fewer skills.

On a Saturday morning my senior staff and I met to decide how we could make it easier for HQ to help us a year from now, without essentially ignoring the needs of the Ugandans we had come to serve. We tried hard, and on Monday morning I sent my Washington colleagues a revised request: of the 17 original skill areas, we had changed eleven of them. We had cut back on our plans as much as we could.

That afternoon brought Washington's response, namely how disappointed they were in me. Foden expressed her bewilderment that none of her suggestions were taken. She also noted that she wanted this matter to be resolved "immediately." Well, I certainly had my come-uppance. Who was I but a Country Director telling Washington what was needed to help avert crises in the nation to which they had assigned me? I wrote a note back saying that we must have been in a different telephone discussion. I prepared a table showing our original request, then the revised one, and how 11 of 17 our positions requested had been changed ("skilled down", although I refrained from that direct characterization).

Now, fully two months since we had first notified Washington of our program needs, I eagerly walked into my office the next morning to open my email for the day's news. Bingo! There was Foden's name. Months of planning and weeks of worry had culminated in this one message: a test of my worth, a barometer of how much Foden realized how hard we had worked to make the post strong. It also would reveal whether we could fulfill our strategy to help some of the poorest peasants in the world. All of this would be rolled into the response on the screen. I clicked to get the message.

The few seconds for the document to come up seemed forever. I gasped… everything we needed was being rejected. All the requests for moderately experienced volunteers were denied. And of the seventeen we needed, we were to be given only six, all generalists. Foden had decided to deny us any volunteers for the eleven remaining slots. We needed to expand and we had submitted a strong program justification for expanding. Instead, we were being cut. Eleven volunteer cuts meant eleven villages that would get no help. Months of planning and weeks of waiting vanished. I sat staring at the screen.

Almost as an afterthought, Foden also had informed me that none of our unfunded requests had been approved. She did not need to elaborate. I got the message. We were to continue running a program that had increased by 100% in volunteer size, and we were to do it with the staff cuts we'd absorbed before Congress increased the Peace Corps budget. What had been taken by Congress, and then restored in spades by Congress, had not trickled down. Foden held it at HQ. It would not reach the volunteers and the villagers of Uganda. I closed my virtually always open door. My office was no longer welcome to the staff who came in many times a day for a quick consult. No longer were my beloved volunteers free to stop by for a quick hello, a hug, a chance to catch up. Weeks of work, a myriad of plans, a keen desire to respond to the needs of struggling peasants in the country I had been sent to serve. It all ended in a cold, bureaucratic nightmare by one paragraph from Foden on the computer screen:

"We tried continuously to work with you to find an agreeable resolution. We are disappointed that you chose not to take any of the recommendations we offered… we'd expected more flexibility and understanding in moving forward." She then lamented again, our "lack of responsiveness" to HQ.

I knew a butt-covering gesture when I saw one. While I was the ostensible recipient of her email, I knew it had been written for people above her, a way to cover herself by painting me as unreasonable. But the veneer of the paint ran thin, and underneath lay things that were not true. She alleged that we had taken none of their recommendations when, in fact, we had taken many of them. We had done all the flexing, but she had not budged. From the start HQ had told me I had missed a deadline I never knew about, and now they would do nothing to provide the type of volunteers we would need more than a year from now.

But Foden was right in saying I did not understand. I did not understand why HQ would not agree to even try to get us the volunteers with the minimum skills we needed. With no other explanation from HQ, their reference to missing a deadline became the explanation. I, the new CD, had missed their artificial deadline.

Understandable? Not to me. I wondered, however, about the level of understanding at Headquarters.

Still green behind my ears at running a Peace Corps post, later that day I was told by Ken Puvak, one of my fellow African CDs in Kenya, that I was being "punished" by the bureaucracy. He had once had his volunteer numbers cut for challenging HQ rigidity and complacency. It was now my turn.

If my HQ colleagues had taken the time to ponder our analyses, to read our reasoned memos, even to discuss with us the needs in Uganda, would their own understanding not have been greater? If they had seen the faces of a family returning to the barren ground of their village after twenty years in a cramped refugee camp, would they have been so quick to refuse to send Americans who would help them dig some wells? If they had thought about how food crises often end up producing the figures of famine-- children with huge tummies and adults with skin hanging from their bones-- would they not have understood why we needed to place workers in crisis?

Even later as I recounted the surprising saga to others, it seemed unreal. Yes, I realized it was not the end of the world. There would be tomorrow, other opportunities, yea more lessons from "the bureaucracy." But even at my age I had believed we were all in it together, the posts at the forefront of what Peace Corps was all about. Headquarters was there to support and assist us. But I was wrong.

The bureaucracy-even the Peace Corps bureaucracy-was not there first and foremost for the peasants of Uganda or, for that matter, peasants anywhere. The bureaucracy was for the bureaucracy. It established demanding, rigid rules and always maintained control in order to ease its own workings. It did not "stretch" or show flexibility when something was needed a bit outside its customary ways of operating.

By having Washington strip me of the volunteers we so desperately, I learned a lesson first-hand that other country directors had warned me about. Long before my own vivid experience with HQ, colleagues told me that basically we all were on our own. Do not rely on HQ for anything, they warned. The bureaucracy serves only itself.

Consigned to defeat for now, I resolved to replace my lost volunteers by bringing in Peace Corps Response volunteers. Response volunteers were people who already had served a full two years in Peace Corps, but who then volunteered to serve an additional six months on special projects. Because their service was handled out of another division of HQ, I decided to work through that program to make up for the two-year volunteers that Foden had stripped from my post. After weeks of planning, submission of paperwork and budget scenarios on our part, the Response Office approved our plan to make up our losses with these former volunteers. While they would not serve as long as regular volunteers (six months instead of two years), at least we could get some skilled volunteers up to the north as families left the IDP camps and sought to settle into their desolate villages.

It was now some weeks after my losing skirmish with HQ, and the new President, Barack Obama, had signaled that he wanted the Peace Corps to grow in size and influence in its service to the world. To demonstrate his resolve, the President had selected a seasoned overseas veteran, Aaron Williams, as his Peace Corps Director nominee. Williams was a former Peace Corps Volunteer himself, serving in the Dominican Republic in the 1960s at the same time that I was serving in India. During his Senate confirmation hearing in August, 2009, Williams had repeated the President's "Peace Corps growth" message.

Since Mr. Obama's swearing-in in January, 2009, the Peace Corps had been run by a George Bush holdover, Jody Olsen. During these months of waiting for Director Williams to be nominated and affirmed, virtually all HQ operations had become a camp of insecure "acting" officials, persons only temporarily holding positions until they received final word about their fates. All the top positions in Peace Corps were unfilled or, to be more accurate, they were filled by people who held the characterization "acting" before the rest of their title. They picked up every tidbit of information that might help them follow the path to their desired permanent positions.

The word about building a larger Peace Corps was duly noted, and the Acting-This and the Acting-That across the bureaucracy fell into a high-speed run, acting as if they not only got the message but had, in fact, been preparing for such growth all along. This pretense, it was felt, would be appealing to the new Director as he arrived. For the acting staff, their "insights" might just land some of the fastest runners a permanent job.

My boss, Lynn Foden, was among those hoping for a permanent position. To prove her mettle in terms of helping to grow the Peace Corps, Foden sent a missive to all County Directors in Africa, telling the twenty-seven of us to let her know immediately how much larger we could build our own posts. With my post already one of the larger ones on the continent in terms of the number of volunteers in service, I bit my tongue by replying that we could take eleven more than we had already requested-- a number that just happened to be the same as the number of slots Foden had stripped from me only weeks earlier. Very quickly she responded to my email. I was told that we would be awarded those eleven additional volunteers… and an additional twenty more as well. It was now clear that HQ never listened to those of us on the ground in Uganda. Foden, the one who had told me early in 2009 that HQ could not deliver the eleven PCVs I needed for the spring of 2010, was now telling me-at a date now only weeks later-that not only could they actually deliver the number I needed, but that they could deliver more than twice as many. And her message came to me not as a query but as an announcement. We would be receiving 31 more volunteers.

I smiled at her audacity. Clearly she must have remembered vividly the punishment she had doled out by stripping me of the volunteers we had needed. Now she had the nerve to say we would get all of them plus twenty more. No comment about incongruity. And certainly no acknowledgment that her original claim that Peace Corps could not deliver the needed volunteers had been patently untrue.

Stripping our post of the volunteers we initially requested had nothing to do with what was possible. It had everything to do with teaching me that Washington rules. Forget what the needs of Ugandan peasants are as they walked back to their villages with no wells and no crops. Washington ruled. Peace Corps posts are simply outposts, a distant second to the needs of headquarters. In the process of learning this hard lesson I also learned another. Peasants come last.

Condolences from Other Africa Country Directors It was not long before word of my punishment spread among fellow Peace Corps Country Directors in Africa. Almost as if traveling by drum beats through the jungle or, in this instance, email messages bouncing off satellites, the grapevine in the Third World worked efficiently and quickly. CDs experienced such frustrations in running their posts that the job itself almost amounted to joining a brotherhood.

Each Country Director had experienced what all others experienced: constant demands from Washington for voluminous reports in impossibly short times, micro-management to the hilt, directives sent from inexperienced staff half our age telling us to do this and that, and always the sobering realization that our post was not really run by us but by the bureaucracy 8,000 miles away. As word spread about what had been done to Peace Corps Uganda, condolences from my colleagues, many of whom I'd never yet met, began to arrive.

Judi and I began a typically sunny Tuesday morning at our Kampala house. The warm sun began to bear down after breakfast as we busily packed to pack to take Ariel to the Entebbe Airport that evening, for her long journey back to Boston. Her senior year at Mt. Holyoke College was approaching and, although this would be the only year we would be unable to accompany her to prepare her dorm room, we all shared the excitement of her final year. My birthday also was approaching, and I felt ecstatic that Judi and Ariel had surprised me with a fly fishing trip soon to come. Better yet, Judi had just been offered a position as a small grants program officer at the Embassy.

An Abrupt End

These pleasures were to be short-lived. I had planned to take the morning off to help Ariel pack for the lengthy trip, but a call to the house interrupted me to come to the office to meet the former Country Director of Peace Corps in Kenya. I could not imagine what had brought Ken Puvak to Kampala, but I went to the office to see. Not yet mid-morning, he and I initially chatted in the open air of the veranda off my second floor office and traded tidbits ever so briefly. When I finally got around to asking what brought him to Kampala, his face went blank. "You don't know?," he muttered in surprise voice. "Washington never contacted you?," he added as I searched his face to find no hint of a joke in progress. Ken stared at me, then at the marble floor of the sunny veranda. I could virtually see him trying to formulate his next words: "Larry, the Acting Director sent me here from Washington. You've been fired."

"Fired…," I responded in virtual disbelief, "Fired for what?"

I looked deeply into Ken's eyes, hoping for the miracle of a glint, a grin to indicate that his harsh message would reveal a dumb joke. I found no such evidence.

"I have no idea, Larry, none whatsoever. They just called me in two days ago to tell me you were being fired, and to get on the plane to be here to take over temporarily when you found out. But I have to be back in Washington in less than a week."

My mind cannot recall what happened next, the back and forth between two startled Peace Corps Country Directors, Ken and his family soon on the way to take up his new post in Indonesia, me with perhaps nowhere to go. Eventually we made our way into my adjoining office to check my email screen for evidence of a message from Headquarters. Many emails scrolled down my screen, most from Washington, but none from Acting Director Jody Olsen, the hold-over Bush appointee who would be leaving office at the end of the week as President Obama's newly appointed person prepared to be sworn in.

Leaving the computer screen Ken and I slinked into chairs at my small conference table, both trying to make some sense of this highly awkward situation. Having awakened several hours before and feeling at the top of my mark, I looked into the face of a colleague at the top of his own and off soon with a young family on a new assignment. Neither of us felt on top of anything at the moment, thanks to the petty mind in Washington that had masterminded the last-minute coup.

"I'm really sorry, Larry," Ken added. "This is awful. Just let me know if there is anything I can do to help." Returning home to help pack for Ariel's return to college I contemplated whether I could mask my emotional state over the course of the afternoon and evening to come, as her plane left at 10:40 p.m. Judi and I spoke ever so briefly when I broke the astounding news to her, and we mutually agreed that the bomb dropped on us had to be a full family matter. Judi understandably felt anger:

"How could they do this? Why? Don't they care that your volunteers and staff love you?"

Ariel, on the other hand, saw the act as a political coup:

"Four days before she leaves office a woman appointed by George Bush fires a CD known to be close to Kennedy and other Democrats. What a surprise!"

Briefly returning to the office late in the afternoon, Ken and I again searched for the letter of dismissal. Somewhat typical of the bumbling ways of bureaucracies, the document that was to have appeared the previous evening finally arrived at 4:20:

"Dear Dr. Brown: This is to notify you that it is my decision that your appointment to the position of Country Director be terminated. Please make all necessary arrangements for packing and shipping of your household effects and separation travel [in the next week]. Thank you for your service. Jody Olsen, Acting Director."

That was it. No reason given. No mention of dissatisfaction. It was as Ken had informed me in the morning… suddenly I was out and nobody was saying why. Nor in my eight months at post had anyone in Washington ever expressed any official concerns about me, my management style or my leadership. In fact, my post was humming like never before.

Our family dinner plans with Ariel went up in smoke. No one felt like eating and in the late afternoon hours I began to contact several colleagues. John Hoover, the DCM (Deputy Chief of Mission) at the Embassy, had gotten a call from Peace Corps HQ.

"They did not call to consult me," Hoover noted. "They did not call to ask me about the impact of losing you to the Mission. They just said you were being fired. No reason. Nothing."

I also shared the Olsen letter with Dave Eckerson, the USAID Director. He had once been the director of human resources for the huge international agency operating out of Washington, and he was stunned by my news:

"You… you just don't do things like this. I mean… this is the federal government. You have protections, due process. If they don't like something, they had to tell you… put it in writing, help you correct it. I have never seen anything like this."

The drive to the airport was laced with the irony and dry humor that characterizes so much of our family's daily discourse. Interspersed with assurances to one another of our long-term well-being, the give and take included a lot of strategic suggestions. We put Ariel on the plane, wondering if the next time we'd see each other was going to be for her December break, as planned, or much sooner.

The next afternoon brought the first news of what was behind my termination. A colleague in the Director's office, apparently upset by Jody Olsen's last major act before leaving, had spoken to enough people to put together the pieces. As Olsen prepared to leave, she wanted several of her people to be appointed to permanent positions by the new Obama team. One of them happened to be the nemesis of Africa country directors, Lynn Foden. Olsen and Foden perceived me to be a threat. Even as a new CD, I was older, vocal, and had good relations with my colleagues at other posts on the continent. Indeed, once I had heard for the umpteenth time of other country directors' raw treatment by HQ, I had written to my fellow Africa CDs, suggesting that the problems we faced were not individual matters to be fixed by each of us. They were systemic problems that we could work together collectively to fix: lack of transparency in the regional budgeting process; constant deadline demands from HQ but often no response whatsoever to our requests; growing numbers of volunteers to train, place and manage but with fewer and fewer staff; and above all a HQ that felt posts exist to serve it rather than the bureaucracy being there to serve the programs in each country.

Other CDs weighed in with ideas and we decided to put our collective thoughts into a memorandum for the incoming Peace Corps Director, Aaron Williams. Our region would be holding a conference in October, and we felt we had the time to produce an insightful and helpful document on the biggest challenges facing Peace Corps Africa, as well as a series of ideas about re-forming the agency for its next fifty years.

The intention may have been good, but it suffered from bad execution. Foden had learned of our concerns and how we planned to raise them, so I emailed her to confirm what she had heard. But I also stressed that our intention was to focus on issues, not personalities. Indeed, I invited her to join us in setting out for the new Director the things we could do to strengthen Peace Corps. I had responded honestly and in an open manner, and some of my fellow CDs later read it and characterized my message to Foden as "collegial" and "constructive."

Collegial or not, within a week of Foden's learning about the letter we were writing for the new Director, her new boss-to-be in Washington, I was fired.

Forty-eight hours after my dismissal I had spoken with key foreign relations staff in Washington, one who worked for Senator Chris Dodd, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations subcommittee that oversees Peace Corps, and the other a top aide to Senator Edward M. Kennedy. While I knew both Dodd and Kennedy personally, each was ill at the time, Dodd with prostate cancer and Kennedy with only a short time to live due to brain cancer. But word did get through: Dodd authorized his staff to investigate my firing and Kennedy sent word through an aide:

"Tell Larry we'll get this fixed." Sadly, Kenendy would be dead before anything could be done by his office.

Meanwhile, I spoke with Ron Tschetter, former Peace Corps Director under George Bush. When Ron left office after Obama's inauguration, his deputy, Jody Olsen had stayed on temporarily as Acting Director. I learned that Olsen recently had called Tschetter to inform him that his old friend was being dismissed.

"I must have gasped aloud on the phone," Tschetter recounted, "because at one point Jody couldn't even get her words out." Apparently sensing Tschetter's shock, Olsen then delivered the coup de grace: "Ron, it's all about the safety and security of Larry's volunteers. I can't say more but that's the reason."

"That's not the story they told me," recalled John Hoover at the Embassy. "They told me you asked too many questions and seemed to be involved in every issue. I got the sense they somehow saw you as a threat."

While different stories to different people may be a time-honored way to get out of a tight spot, I took the allegation served up to Tschetter more seriously. To be sure I laughed out loud when he recounted Olsen's professed concern: Of all the things I had done in my months in Uganda, I had done the most to insure volunteer safety and security, even to the point of being overly-cautions. While the PCVs understood that my motives were good, they often felt I was too cautious, too much the "Jewish father" wanting to protect them from crimes and other risks during their service. But I was resolute. Protecting them was my key responsibility, and I was gratified that while six volunteers had been the victims of assaults in the eight months before I arrived, only one had been assaulted on my own watch in the same amount of times.

But Olsen's allegation was not about the truth or, for that matter, even about safety. Had HQ ever had any concern about my protecting the safety of volunteers, they would have expressed it quickly, and legitimately so. I would have gotten emails, calls, even a notice that they were sending out a team to help me. Indeed, HQ would have been remiss not to act were the concern valid. But none of this ever happened. Olsen's allegation simply was designed to slander me over the one issue in Peace Corps that really makes everyone nervous: volunteer security.

To call a CD lacking in this arena is like accusing a teacher of child molestation. He may not be guilty, but no one will rush to defend him. The alleged act, itself, was emotionally packed. It was nuclear. No one would want to touch the matter. By charging that I was not protecting my volunteers adequately, Olsen acted to preclude any support for my re-instatement. Nevertheless, I compiled a list of all safety and security policies and plans implemented during my tenure just in case Olsen trotted out the baseless charge again.

Kennedy and Dodd's staff called me again on a Monday evening in Kampala, almost a week after I had been fired. They assured me that they were on the case and offered to give several updates. We agreed to talk again later in the week, but it was not to happen. The headlines carried the news the next day that Senator Kennedy had succumbed in his last noble battle.

It's a good thing Kampala time is seven hours ahead of the East Coast of the United States, because Judi and I had several hours to mourn, commiserate, even send off emails to friends still sleeping in the U.S., who remained unaware of Kennedy's death. We also wrote Ariel a note saying how lucky she had been to have known the nation's greatest senator, and to have talked with him and eaten at his table.

But the mourning was not to be tolerated. Only hours after Kennedy's death had become known across America, Peace Corps HQ was sending my staff directives: cut Brown's email; take his cell phone; get his office keys; tell him to vacate his house. The insensitivity of it all felt overwhelming, but further thought led me to realize that this was the exact purpose of this series of intrusions. Several of the people at HQ were aware of my closeness to the Senator, even as their demands upon me continued during the days between his death and his funeral service. Foden and Olsen were intent on seeing that my life and that of my family was uprooted, the sooner the better.

All the while I was struggling for time, time to let colleagues get in touch with Aaron Williams to tell him what had happened, time for the Senate staffers to do their magic, and now time for all of Washington and much of the world to grieve for Ted Kennedy. But struggle as I might for time, HQ kept the pressure up, on a daily basis. And all of it, I learned, was being orchestrated by the General Counsel, Carl Sosebee, along with Lynn Foden now that Jody Olsen had become history at the agency.

Sosebee and Foden wanted me out. The General Counsel's Office had returned for one more poisonous bite, this time not by Nancy Miller, the self-styled ethics queen, but by the GC himself. Both he and Foden wanted me removed before I or anyone else could organize a response to the coup that had canned me. Only later did I learn that Foden and Sosebee already had colluded to orchestrate the departure of several other African County Directors, seasoned people like me who were unafraid to speak out about problems and possible resolutions. By the time they elected to target me, this dynamic duo had been perfecting efficient ways to do bad things to the people in the field who best knew Peace Corps programs and how to run them. As we prepared to leave Uganda, my staff wanted to meet with me in our large conference room to say goodbye. Happily I agreed, knowing that while the event would be emotional for all of us, both they and I needed some closure. But the day of the event, as we dressed to prepare for leaving the house, I received a call from the office. From Washington, Foden and Sosebee had instructed that I not be allowed to return to the office. I would not be allowed to bid farewell to my staff. I would never see them again.

Click this link to read the conclusion of "Peasants Come Last."

About the Book

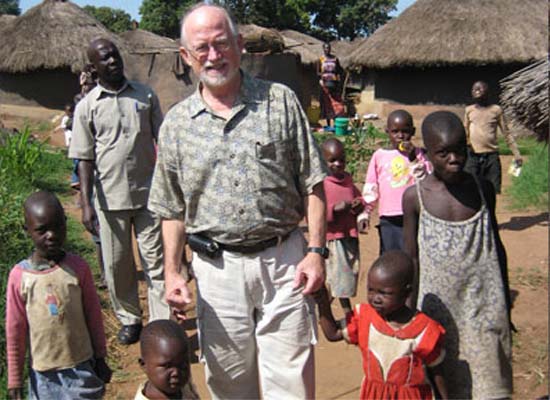

In the tradition of popular activist scholars like Carl Sagan and Stephen Jay Gould, J. Larry Brown has spent decades linking the findings of science to the realities of human existence. He gives us a candid look at what it means to try to do good things in a harsh world. We are taken to the make-shift huts of refugees driven from their homes by the insane barbarism of the Lord's Resistance Army. We stand with Brown where Livingstone once stood, at Murchison Falls overlooking the powerful Nile filled with hippos and crocodiles. We see the grinding lives of people who eat the same meal every day. But of all the obstacles faced by Brown and his colleagues, none is as nonsensical as the tone-deaf dealings of Washington. We see how the needs of peasants come last when the realities of their lives are no match for the machinations of Washington's rigid routines.

Purchase the book at Amazon.

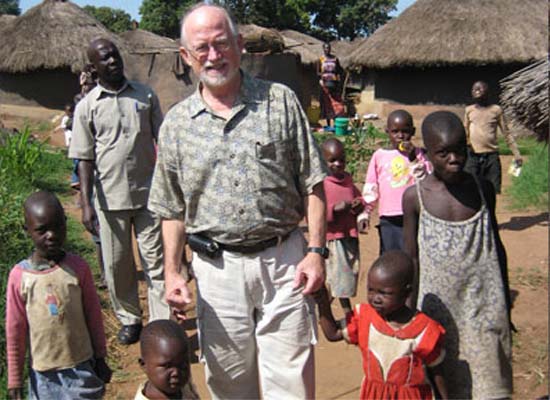

About the Author

Serving many years on the faculty of the Harvard School of Public Health, Dr. J. Larry Brown riveted national attention to the existence of hunger in America in the 1980's, when he led a team of prominent doctors on field investigations into twenty-five states. The founding director of the Center on Hunger and Poverty, Brown also founded the Feinstein Famine Center and the Institute on Assets and Social Policy. Dr. Brown chaired the board of Oxfam America, and also chaired the medical task force of USA for Africa and Hands Across America. He is the author of numerous articles in both lay and scientific journals, such as Scientific American and Encyclopedia Britannica, and several books including Living Hungry in America. He has appeared often on national television including CNN, Good Morning America, Today Show, and network news programs, and testifies frequently before Congress. A young Peace Corps Volunteer in rural India in the late 1960s, Brown later served under President Carter as Assistant Director of the Peace Corps. He recently served a stint as Country Director for the Peace Corps in Uganda, and now resides with his wife, Judi Garfinkel, in Oman, where they head programs for World Learning/SIT.

Links to Related Topics (Tags):

Headlines: October, 2011; Peace Corps Headquarters; Criticism; Country Directors - Uganda; Speaking Out; Peace Corps Uganda; Directory of Uganda RPCVs; Messages and Announcements for Uganda RPCVs

When this story was posted in October 2011, this was on the front page of PCOL:

Peace Corps Online The Independent News Forum serving Returned Peace Corps Volunteers

| Peace Corps: The Next Fifty Years

As we move into the Peace Corps' second fifty years, what single improvement would most benefit the mission of the Peace Corps? Read our op-ed about the creation of a private charitable non-profit corporation, independent of the US government, whose focus would be to provide support and funding for third goal activities. Returned Volunteers need President Obama to support the enabling legislation, already written and vetted, to create the Peace Corps Foundation. RPCVs will do the rest. |

| How Volunteers Remember Sarge

As the Peace Corps' Founding Director Sargent Shriver laid the foundations for the most lasting accomplishment of the Kennedy presidency. Shriver spoke to returned volunteers at the Peace Vigil at Lincoln Memorial in September, 2001 for the Peace Corps 40th. "The challenge I believe is simple - simple to express but difficult to fulfill. That challenge is expressed in these words: PCV's - stay as you are. Be servants of peace. Work at home as you have worked abroad. Humbly, persistently, intelligently. Weep with those who are sorrowful, Care for those who are sick. Serve your wives, serve your husbands, serve your families, serve your neighbors, serve your cities, serve the poor, join others who also serve," said Shriver. "Serve, Serve, Serve. That's the answer, that's the objective, that's the challenge." |

Read the stories and leave your comments.

Some postings on Peace Corps Online are provided to the individual members of this group without permission of the copyright owner for the non-profit purposes of criticism, comment, education, scholarship, and research under the "Fair Use" provisions of U.S. Government copyright laws and they may not be distributed further without permission of the copyright owner. Peace Corps Online does not vouch for the accuracy of the content of the postings, which is the sole responsibility of the copyright holder.

Story Source: Peace Corps Online

This story has been posted in the following forums: : Headlines; Headquarters; Criticism; Country Directors - Uganda; Speaking Out; COS - Uganda

PCOL47504

78