Charles S. Houston - At Home in High Places

Charles S. Houston - First Director of Peace Corps India - At Home in High Places

Charles S. Houston - First Director of Peace Corps India - At Home in High Places

Charles S. Houston: At Home in High Places

A close-up taken at 26,000 feet shows the frost on his beard, a curl of rope attached to the cliff above his head, the white of his teeth, and an unmistakable smile on his lips. The year is 1938, the place K2, pinnacle of central Asia’s towering Karakoram Range, the second highest mountain in the world, and among the most difficult to climb. Charles S. Houston’39 is in his element.

"Not Conquerors, but Pilgrims"

Lest anyone mistake the climber’s expression for the smile of conquest, consider the lines of a poem he wrote to commemorate an earlier ascent up the slope of Nanda Devi in India, 25,600 feet high and then the highest place on Earth ever reached by man (American Alpine Journal, 1995):

"Not conquerors, but pilgrims, seeking Light not fame."

Or as he would put it in his book, "Going Higher-Oxygen, Man, and Mountains" (reissued in its fourth edition by the Mountaineers, Seattle, 1998): "Enjoy the mountains; they have beauty and wisdom for us if we approach them with humility, respect, and knowledge."

Throughout his multifaceted career as mountaineer, scientist, teacher, and physician, Charles Houston, one of the world’s foremost authorities on high altitude medicine, has been gathering and disseminating the knowledge of high places as a humbling prerequisite for respect. Not a man to be easily pigeonholed, Houston is also, among a long list of accomplishments, the inventor of a mechanical heart (the forerunner of the Jarvik artificial heart), a former Peace Corps director for India, and a pioneer in group practice and community medicine. The common denominator, if there is one, is a sense of life as a great adventure.

A Yankee in the Court of Genghis Khan

The snow drifts seen through the living room window of his cozy home in Burlington, Vt., make a fitting backdrop. Outside, a red-headed cardinal, a velvet gray titmouse, and a gold and a purple finch flit across the whiteness, vying for seed from a freestanding feeder. Inside, the walls and shelves are covered with Himalayan, Indian, and Tibetan art and artifacts, much of it on a mountain theme. The collection is under the watchful and distinctly Occidental eye of an ancestor, General Charles Scott, a hero of the American Revolution, portrayed in a Gilbert Stuart painting.

At 86 and counting, Dr. Houston is the incarnation of that odd admixture of mystery and matter-of-fact, Yankee and yak. Compact and spry, flinty-eyed, and gnomelike of expression, he acknowledges with a twinkle that some might find him "difficult," or as he prefers to put it, "a pusher." He carefully selects his words, footholds in the conceptual ascent, like the lifelong climber that he is. The conversation leaps from pre-Incan human sacrifice at shrines above 22,000 feet and the Chinese tradition of mountain painting, poetry, and pilgrimg to the geological substrata of mountain worship and the lack of punctuation in the Biblical Hebrew passage: "I will look to the hills from whence cometh my strength." But there is nothing misty-eyed about the man. His sharp gaze immediately engages the visitor and makes of him a partner in a shared quest. The look belies a boundless curiosity filtered through the hard light of science.

Medicine, a Calling that Came Early

Science was his first love, medicine a calling that came early. The loan of a microscope by a physician friend of the family when he was 10 prompted him to investigate the world around him, to dissect and study insects and dead animals. Looking back, he confirms, "I’ve never thought of any other career but medicine."

Earning his undergraduate degree at Harvard, Houston entered P&S, where he came under the influence of Atchley and Loeb. Robert Loeb, an early role model with whom he remained lifelong friends, "was so perceptive," Houston shakes his head in admiration, "he never missed a trick. He was remorseless in pointing out things in patients we’d missed." Sixty years after the fact, Dr. Houston delights in reenacting a typical colloquy with Dr. Loeb: "‘Did you look at the fingernails?’ ‘What?’ ‘Well, look at them! Did you notice that coffee stain on the back of his hands?’" Dana Atchley, a mentor to both him and his future wife, Dorcas, then head nurse on the male ward at Presbyterian Hospital, was "exactly the opposite, quiet and very meticulous . . . Loeb was physical, physical, physical. Atchley: history, history, history-together they made an inimitable team."

The Call of the Hills

As a Harvard undergraduate and active member of the illustrious Harvard Mountaineering Club, a brotherhood of virtuoso climbers and explorers, he’d already participated in pioneering ascents of Alaska’s Mount Crillon and the forbidding Mount Foraker.

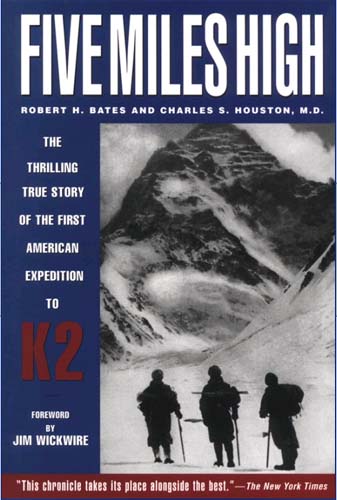

On two leaves of absence from P&S, young Houston made mountaineering history: first in 1936, as the member of a celebrated expedition led by the British climber H.W. Tilman up Nanda Devi in India, then the highest mountain ever climbed, and a second time in 1938, himself the leader of the first American Karakoram expedition to K2. Though his party did not reach the summit, they climbed the cone (at 26,000 feet) and mapped a feasible route to the top later followed by an Italian team in the first successful ascent in 1954. Nature’s hazards and hurdles notwithstanding, as Houston reminded a P&S audience upon his return, "there is risk to mountain climbing, but there is also danger walking the streets of New York." Dean Willard Rappleye, who was in the audience, called it "one of the most entertaining evenings I have had the privilege to attend" and saluted the speaker as "a man of many talents."

An ill-fated return in 1953, in which one of his teammates, Art Gilkey, perished, inspired the book, "K2-The Savage Mountain." Gilkey contracted thrombophlebitis and had to be carried. As leader and medical member of the expedition, Dr. Houston, who himself suffered a concussion in a valiant attempt to save his friend, took the death particularly hard. It was to be his last major ascent. "When I thought about it later," he says, "it wasn’t fair to my wife and children. I was close enough to my own demise. That was the end of my climbing, period!" He and the other surviving members of the team later received the David Sowles Award of the American Alpine Club for their unselfish action in assisting a fellow climber.

In a memorable passage, Dr. Houston (who co-authored the book with fellow climber Robert H. Bates) gives a lyric evocation of just what it is that makes humans want to climb mountains, despite the risk:

"The answer cannot be simple; it is compounded of such elements as the great beauty of clear cold air, of colors beyond the ordinary, of the lure of unknown regions beyond the rim of experience . . . the thrill of danger-but danger controlled by skill . . . How can I phrase what seems to me the most important reason of all? It is the chance to . . . strip off non-essentials, to come down to the core of life itself . . . "

Among his other mountaineering exploits, Dr. Houston led an expedition to the foot of Mount Everest in Nepal in 1949; its members included his father, Oscar Houston, and H.W. Tilman. Scanning the south face, the first Westerners to do so, Houston’s team plotted the route that would eventually be taken in 1953 by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay on their successful ascent.

Adventures in High Altitude Medicine

Following a medical internship in medicine at Presbyterian Hospital, Dr. Houston volunteered in 1941 for a commission in the U.S. Navy. Based in Pensacola, Fla., he coordinated the Navy’s high altitude training programs for aviators and directed a landmark high altitude study called "Operation Everest." Houston argued that "if aviators were acclimatized to a moderate altitude, like 15,000 feet, they could then fly higher," a definite tactical advantage before the days of pressurization. His educated hunch proved to be right and Houston earned his flight surgeon wings. Declining the Navy’s bid to sign on as medical director of the nuclear experiments at Bikini, Dr. Houston resigned his commission and returned to civilian life.

Before the war, he and P&S classmate Henry Saltonstall’39 had planned to practice together in a peaceful rural setting. Following a brief stint at Bellevue Hospital, Houston joined his old friend and two other physicians in 1952 to open the Exeter Clinic in Exeter, N.H., the third group practice in New England. There he enjoyed the life of an old-fashioned country doctor, on occasion skiing out to visit snow-bound patients.

Then in 1957, an adventure of another kind lured him to Aspen, Colo. Walter Paepcke, a successful Chicago businessman, and his wife, Elizabeth, conceived the idea of the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies, whose grand opening included concerts and lectures by Albert Schweitzer. Recruiting Mortimer Adler to head up the humanistic program, Paepcke persuaded Dr. Houston to serve as founding medical director of the Aspen Health Center. Conceived as a health refuge for America’s leaders in business, labor, government, and the professions, the center’s espoused purpose was to "prevent rather than to treat illness due to stress," an idea well ahead of its time.

"The complete man," according to a prospectus written by the new medical director, "must be more than a properly nourished, well-muscled person. His mind and spirit also need stimulation . . . He needs experiences outside of, as well as within, his profession. If not, he is living on his intellectual capital, and he may well become bankrupt in spirit." Dr. Houston organized a daily fitness regimen, led discussions, and lectured on health-related concerns. The center lasted only a few years, but it helped pave the way for a new interest in preventive and holistic medicine.

Dr. Houston stayed on in Aspen, where he built another group practice. A number of his patients suffered from advanced rheumatic heart disease. He spent his spare time in a workshop he set up in the garage and conceived one of the early models of an artificial heart. Attracting NIH funding, he worked with a surgeon, installing his mechanical device in experimental animals and keeping them alive for 12 to 24 hours.

His rescue of a skier who had fallen sick from what appeared to be pneumonia at 12,000 feet led to another discovery. Taken down to a hospital in Aspen, the patient quickly recovered. Baffled at first, Dr. Houston published in 1960 the first documented case of high altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE), in the New England Journal of Medicine. HAPE is a life-threatening condition of the lungs caused by a lack of oxygen.

Of Poultry and Peace: Adventures in the Peace Corps

A call from Washington, D.C., once again led Dr. Houston and his clan to decamp, this time for India. The Peace Corps had been created by President Kennedy. Its founding director, Sargent Shriver, had heard of Houston’s Himalayan exploits and persuaded him to take on operations in India. "It was unbelievable," he recalls of the experience. "Every day there was some crisis, something different and exciting, or dangerous or frightening." Directing a volunteer force that started with six and soon swelled to 250, with another 900 on the way, Dr. Houston oversaw programs in nursing, farming, English language instruction, digging wells, producing farm instruments, raising chickens, and almost anything else under the sun. The Peace Corps’ greatest benefit, he believes, was to the volunteers themselves and to America. "They’ve become a very distinguished sensitized segment of society," he says, citing career diplomats and college presidents among former volunteers. One of his sons, Robin, became a Peace Corps doctor in Nepal and continues to work in the field of international public health.

President Kennedy infused the nation with a rush of idealism. Remembering that moment, Dr. Houston reflects: "We believed we were going to change the world, or at least to nudge it, and in fact, we did, though other forces pushed back the progress."

Recalled to Washington to create a Doctors Peace Corps, Dr. Houston managed, among other noteworthy accomplishments, to help create a medical school in Jalalabad, Afghanistan, before the rapidly escalating war in Vietnam put a stop to his plans.

Bringing the Medical Message Back Home

Uncertain of what to do next, Dr. Houston attended a meeting of international medical educators, at which he happened to be seated next to the dean of the University of Vermont’s medical school in Burlington. The dean mentioned the creation of a Department of Community Medicine for which they were seeking a chair. So the Houstons once again packed up and moved to the Green Mountains.

While Dr. Houston managed to create a number of innovative programs in the course of his tenure, including a popular externship with rural practitioners, a turf conflict ensued between his department and the Department of Medicine. "I wasn’t terribly diplomatic," Dr. Houston admits. Community medicine was abolished and its erstwhile chairman, who had a joint appointment in medicine, stayed on until his mandatory retirement at 65.

Ever the "pusher" and doer, Dr. Houston perceived his academic role in community medicine as transcending the strict boundaries of the academy. He served on the Vermont governor’s commission that wrote the landmark 250 Environmental Protection Act in 1968. And from 1991 to 1992, he was a member of the governor’s health care reform commission created to develop a viable health care system for Vermont.

More Medicine from on High

His primary research efforts, meanwhile, continued to focus on high altitude medicine and physiology. From 1967 to 1979, he headed the high altitude physiology study on Mount Logan in Canada. The study yielded 20 papers and led to the description of an undocumented medical condition, high altitude retinal hemorrhage (HARH). It also identified ataxia, the staggering gate, as an early warning sign of the onset of brain edema.

In 1975, he launched the first Mountain Medicine Symposium, subsequently expanded and renamed the International Hypoxia Symposium, the premier worldwide venue for high altitude studies, which he co-chaired until 1997.The field of high altitude physiology and medicine has grown immeasurably since he helped put it on the map. And while Dr. Houston, the veteran climber, decries the overcommercialization of mountaineering and an irresponsible amateurism leading to such disasters as the tragic deaths on Everest in 1996 (as described in Jon Krakauer’s bestselling "Into Thin Air"), Dr. Houston, the high altitude doctor, welcomes the burgeoning wealth of knowledge of high altitude conditions. His book, "Going Higher," is considered a classic compendium for climbers and physicians alike. In 1997, he received the coveted King Albert Medal of Merit Award for his contributions to the understanding of mountain sickness and man’s acclimatization to high altitude.

A medical colleague and longtime admirer, Dr. Sam Silverstein, the John C. Dalton Professor and Chairman of Physiology and Cellular Biophysics at P&S, himself an avid climber, calls Dr. Houston "a true explorer in every sense of the word. In search of new challenges, he has never followed any prescribed path, always wanting to cross new ridges and see what’s on the other side.""My greatest success," Dr. Houston demurs, "is, with my wife, to have raised three wonderful children." His wife, Dorcas, died June 26, 1999, a week before their 58th wedding anniversary.

Advancing years have not diminished his activity. He served as a consultant to NASA on a recent Everest expedition, an adviser to the producers of the IMAX film, "Everest, Mountain Without Mercy," and a contributor to the companion text published by the National Geographic Society.

Ever restless, Dr. Houston peers out the window. "The feeder needs refilling," he observes, donning boots and gear, trudging out into the snow to feed the birds.