During the late 1970s, Joseph Opala, an American anthropologist working in Sierra Leone, set out to study the "Gullah connection"--the relationship between slavery in coastal South Carolina and Georgia and the thousands of men and women abducted from the Rice Coast of West Africa.

The Power Of Memory. - Review - movie review

American Visions, Dec, 1999 by Nashormeh N.R. Lindo

new

The first frames of the documentary film The Language You Cry In reveal an eclipse of the sun. Nomadic clouds obscure the heavens, concealing and then uncovering the phenomenal layering of shadow and light. The prophetic swirling of the wind haunts one's ears and soul, even as the voice-over of Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor stirs the consciousness: "Africa, 18th century. A young woman is snatched from her village by slave traders, forced to part forever from her mother, her motherland, her language, her identity. This is the nonhistory of millions of African-American women and men: a wall of silence--a mysterious past that memory fights to preserve from the onslaught of time, but which ends up shrouded in darkness."

In a mere 52 minutes and 34 seconds, The Language You Cry In makes plain the force of memory and the power of storytelling to recover lost truths. Directed and produced by Alvaro Toepke and Angel Serrano, the film tells the story of how a single word, contained within a simple African sorrow song, helped lift the veil that concealed one American family's African past.

The quest began with a simple song--a funeral dirge, an African blues song. During the 1920s and 1930s, Lorenzo D. Turner, a noted African-American linguist who was then a professor at Fisk University, began researching African retentions in the speech patterns and dialects of African Americans in the Southern United States. He was particularly interested in the language of the Gullah peoples who had inhabited the Sea Islands and coasts of South Carolina and Georgia since the 18th century.

Isolated from mainstream culture and maintaining their distinct social structure, the Gullahs had preserved more Africanisms within their traditions than had any other group in the United States. Much of the early analysis of the Gullah dialect was tainted by racist suppositions about the inability of former slaves to maintain their African identities. Turner noted in the preface to his 1949 book Africanisms in the Gullah Dialect: "The assumption on the part of many has been that the peculiarities of the dialect are traceable almost entirely to the British dialects of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and to a form of baby-talk adopted by masters of the slaves to facilitate oral communication between themselves and the slaves." However, Turner's study of Gullah culture, music, folklore and linguistic patterns made a convincing case for the existence of African retentions in North America.

Turner's travels took him to the Sea Islands of Georgia and South Carolina. He tape-recorded the region's distinctive language and folklore and cataloged more than 3,000 Gullah names and words that had African origins. It was the research he conducted in 1931 in the fishing village of Harris Neck, Ga., that unearthed the seed that decades later would inspire the makers of The Language You Cry In.

In Harris Neck, Turner discovered Amelia Dawley, a 50-year-old woman whose family had moved to the region after their emancipation from slavery. Turner's recording of Dawley included the woman's rendering of a song she had learned as a child. The melody was haunting, but the words, part of an unfamiliar language, could not be understood.

According to scholars, the words of Dawley's song constitute the longest known text in an African language introduced by slaves into North America. Solomon Coker, a Sierra Leonean graduate student who was working with Turner, recognized a word in the song that belonged to his own Mende language: kambei, a word that means "grave," supplied an important clue. Coker suspected that Dawley had passed along a funeral song.

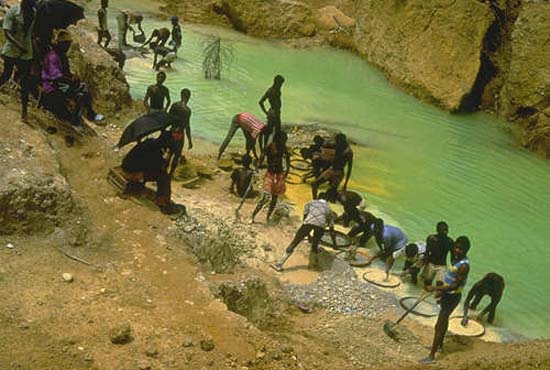

With this historical backdrop securely in place, filmmakers Toepke and Serrano draw recent players and events onto center stage. During the late 1970s, Joseph Opala, an American anthropologist working in Sierra Leone, set out to study the "Gullah connection"--the relationship between slavery in coastal South Carolina and Georgia and the thousands of men and women abducted from the Rice Coast of West Africa. Expert rice farmers, these people brought a high price on the slave market. They also arrived in America armed with their own traditions and, of course, their songs.

Persuaded of this cross-Atlantic bloodline, the government of Sierra Leone in 1989 invited a delegation of Americans from the Gullah region to visit Sierra Leone. OPala was asked to help plan the welcoming reception. He enlisted the support of the Freetown Players and began searching for music that could serve as a tribute. It was then that Opala discovered the tapes of Lorenzo Turner and the song of Amelia Dawley.

The song's power continued to transcend the questions about its words' meaning. Following the performance for the Gullah visitors, Opala convinced ethnomusicologist Cynthia Schmidt and linguist Tazieff Koroma to join him in a search for the song's origins.

In 1990, Opala, Schmidt and Koroma began traveling to villages in the Pjuha District, to areas inhabited by the Mende people. At each village, they talked with the village elders and played the tape of Dawley's voice, hoping for a moment of revelation. The initial results were discouraging. "They recognized one or two words, but not the song," Schmidt recalls.

The scholars began considering that their search might prove to be futile--that the source of the song might in fact be lost. Then one day, Schmidt ventured alone to the village of Senehun Ngola, beyond the boundaries of the area that she and her colleagues had targeted. When she began playing the tape, decades of silence were broken. After the very first phrases, the women of the village began to sing along.

The melody was rather different, but the words were identical to those recorded by Turner in 1931 and translated by Turner and again later by Koroma. "Everybody come. Everybody come together," the women sang in their language. "The grave is restless. The grave is not yet at peace."

It was time to complete the connection. Opala returned to the United States, and in Harris Neck, a member of the 1989 Gullah delegation introduced him to Mary Moran, the daughter of Amelia Dawley. Moran had also learned the song and had shared it with her children.

"I just thought it was a little something to dance by," Moran admits. "I did not know that it was a funeral hymn. Probably if I'd known, I never would have danced to that little old song, but I didn't know no better." Moran adds that Dawley "didn't know what it was herself. That was the way my grandmother taught it to her. She taught it to us."

News of the discovery spread through the media, both in the United States and in Sierra Leone. The Moran family received an official invitation to visit the land of their ancestors--a trip that was delayed for a while by the civil war taking place in the region. When they at last made their historic journey, in 1997, reports of the family's arrival were the day's headlines. Nevertheless, the significance of the odyssey far exceeded its newsworthiness. "Memory is power," Grosvenor states in the film's narrative. "Neither time nor centuries of oppression have been able to erase America's African heritage."

For Dawley's descendants, the discovery had profound meaning. "That part of the history was blank," says Dawley's grandson Wilson Moran. "There were no names, no records, nothing that would connect me to a place in Africa, other than that somebody in my family was brought over here. From where? South Africa? West Africa? Middle Africa? Where? We had no earthly idea. So we knew that we had some connection to Africa, but we were still a stranger to Africa. Now I feel that we're no longer a stranger. There is a place from whence some of my people came."

The film's portrayal of the Sierra Leoneans' experience transports the answer to Moran's questions beyond the discovery of identity. One sees life as it might be for those spared the Middle Passage: a village ravaged by war; women, entrusted with the ceremonies of birth and death, covering themselves with white clay in preparation for a burial ceremony; the killing and cooking of chickens and the communal platter of red rice--a meal that is a central part of the Tenjami rite of burial.

Also, one discovers that in some instances, remembering has been as important to those who remained behind as it was for those who were taken from their homeland. The traditional rituals of worship had been supplanted by the Islamic and Christian religions; yet there were those, like Bendu Jabati, who were prepared to understand and uphold the ancestral inheritance. Jabati was one of the women who recognized Dawley's song and who would help prepare for the Moran homecoming.

Jabati says: "That song brought back memories of my grandmother knocking me on my head and saying, `Sometime in the future, when you hear anyone singing this song, you will be able to identify who that person is.' I believe that my grandmother told the truth--that those singing this song are my brothers and sisters."

Hundreds of neighboring villagers journeyed to Senehun Ngola on the day of the Moran family's arrival. The film captures their mighty procession, as well as the stalwart presence of the young warriors who encircled the area to ensure that the country's wars did not interrupt the celebration. When Bendu Jabati and Mary Moran at last meet and embrace--and as the families share their respective renditions of their inherited song--the tears shed reach not only beyond miles and years, but also beyond videotape and television screen, to touch the viewer's heart and understanding.

The film conveys a poignant statement about the power of the word. It reinforces, with tremendous emotional impact, the fact that African people were determined to resist the complete enslavement of the spirit that accompanies the eradication of memory. The slave traders were wrong. They thought that we would not be able to return. However, the powerful and liberating oral tradition can be spoken or sung.

"The song was never that important to me until I found out where it came from," says Mary Moran. "Then I thought of the woman who brought it over, and I thought, The only thing she could take from Africa with her was this song in her heart."

Village elder Nabi Jah allows a Mende proverb to explain why the funeral song has survived his people's enslavement in America: "You can speak another language, you can live in another culture, but to cry over your dead, you always go back to your mother tongue--the language you cry in."

For more information, contact California Newsreel (415) 621-6196 http://www.newsreel.org

Nashormeh N.R. Lindo is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

COPYRIGHT 1999 American Visions Media, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group