Priscilla, a slave story - researched by Joseph Opala - She was stolen from Africa. And brought to America, in a ship owned by Rhode Island merchant (Part 1)

Priscilla, Part one: PRISCILLA, a slave story

She was stolen from Africa. And brought to America, in a ship owned by Rhode Island merchants. Her story is 1 in 11 million. That's because -- unlike the others -- it can be told. Two scholars and a group of Rhode Island artists have completed the circle

01:08 AM EST on Sunday, February 13, 2005

BY PAUL DAVIS

Journal Staff Writer

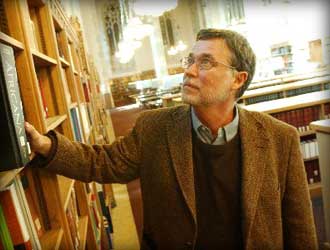

Caption: Anthropologist Joseph Opala (RPCV Sierra Leone) in the library at Yale University. Opala has spent 30 years researching the slave trae between Sierra Leone and South Carolina. Journal photo / Frieda Squires

No one knows her real name.

As a little girl she sang and played games in a village 100 miles from the West African coast. Beneath a grass roof she slept on a bed of clay.

During the growing season, nearly 200 inches of rain pelted the tall palms and spiky grasslands. But when the sun broke through, the rice and fields sparkled like emeralds.

Dressed only in a lapa, or skirt, the girl carried water in a pot on her head, fetched firewood or swept the floor of her family's stick-and-mud house.

In the spring and summer, her family worked in the sprawling rice fields. The girl pulled weeds or sharpened hoes, sometimes in heavy rain. In a society where elders were revered, children worked.

It was nothing like the horror to come.

In 1756, slave traders raided her village. The Africans -- probably from the interior Fula, Susu or Mandingo tribes -- slashed the air with European or locally made swords and fired muskets made in England, Germany or Holland. They may have slaughtered babies or disemboweled some of the elders.

The raiders marched the girl and other captives down dirt footpaths to the coast. Adults were tied together by ropes around their necks; ropes bound their wrists, too. Some carried cow hides, ivory tusks and wax, goods valued by white buyers.

The little girl may have been sold to an African trader, a middleman operating along a river route. She may have been delivered to an African, European or Afro-European buyer stationed at a coastal trading post, where a dozen or more men lived in mud huts.

Or she may have been ferried to Bunce Island, a British slave-trading fort in the the Sierra Leone River. Employing between 50 and 75 whites, it was one of 40 slave castles on the African coast, and the only major British fort along the Rice Coast, a region stretching from modern Senegal in the north to Liberia in the south.

In the late 1600s, the Royal African Company of England had built a commercial fort on the island. Around 1750, the London firm of Grant, Sargent and Oswald added a shipyard and a fleet of vessels to scour the Rice Coast for slaves.

On Bunce Island, a lookout tower loomed above a high-walled holding pen for the African captives, who were separated by age and sex. Canons pointed inward at the prison.

On the African shore, the girl awaited her fate.

ON THE OTHER SIDE of the world, William Vernon and his brother Samuel counted on the trading posts of western africa to help maintain their place in Newport society.

William prayed at the Second Congregational Church, spoke several languages and read widely. A founding member of the city's Artillery Company, he was "known all over the continent of America," noted a French observer.

And Newport was known all over the world. From 1725 to 1807, more than 900 Newport vessels shipped 100,000 Africans to the Caribbean, Brazil and the colonies.

Newport ships carried rum to West Africa and traded it and other goods for Africans. The captives were then carried to the West Indies or the colonies. Ships returning from South Carolina carried barrels of rice; those from the West Indies carried sugar and molasses, to make more rum.

Newport's noisy waterfront was rimmed by rope makers, rum distilleries, taverns, sail lofts, snuff-makers and chocolate grinders. The smell of cocoa and molasses clashed with the stink of fish, boiling alcohol and whale guts used to make candles.

Before the Revolution, nearly a fifth of Newport's population was black. And a third of the city's residents owned at least one slave; many families would own more.

Advertisements in the Newport Gazette touted the arrival of "extremely fine, healthy, well limb'd Gold Coast slaves, men, women, boys and girls. Gentlemen in town and country have now an opportunity to furnish themselves with such as will suit them . . . "

William and his older brother, who had formed a trading firm in the 1750s, owned a sloop named the Hare.

On Nov. 8, 1755, Capt. Caleb Godfrey received orders from the Vernons. Godfrey, they said, must take the "first favorable Wind" and "proceed directly to the Coast of Africa, where being arrived you are at Liberty to trade at such Places as you think most for our Interest.

"Don't purchase any small or old Slaves," they cautioned. Instead, they said, buy young males who "answer better than Women." When his ship was full of slaves he should "Keep a watchful Eye over 'em and give them no Opportunity of making an Insurrection, and let them have a Sufficiency of good Diet, as you are Sensible your Voyage depends up their Health."

Godfrey was a tough, experienced slaver. If crew members became drunk or unruly, he put them in chains. Crew members cursed at him. Once, he turned his back on a leopard chained aboard ship in Sierra Leone. The leopard clawed his neck. After four days in the infirmary, he was back at the helm.

He crossed the Atlantic with a 15-man crew and steered his sloop along Africa's west coast, following the prevailing winds and currents.

It was tricky terrain, populated by slave raiders, African kings, traders and middlemen. No single polity -- European or African -- ruled the region. African chiefs demanded gifts and cordial relationships. Trading posts operated from every river mouth. Malaria thrived in the hot, humid climate.

Using a pidgin English to bicker, Godfrey bought goods and slaves from the Rio Pongo River to the Sierra Leone River, a 100-mile stretch.

He used the British fort at Bunce Island as a base.

"It was a seller's market," says Joseph Opala, an anthropologist at James Madison University in Virginia. "They tried to give him poorer quality slaves for high prices."

On April 9, 1756, Godfrey wrote the Vernons a brief letter.

"I have now Eighty Slaves aboard and Expect to Sale for Carolina tomorrow my Vessl is in Good order Clean tallowd down to the Keel."

Among them was the little girl.

GODFREY HAD TIMED his voyage carefully, arriving in Africa at a time when the rivers were navigable. He left before the heavy rains erased trade paths and flooded local rivers.

Aboard the Hare, the men were kept below deck in chains. The women and children, in separate quarters, had more freedom, but they also had to cook or clean.

Godfrey left no record of his treatment of the Hare's cargo.

But for many Africans, the transatlantic voyage, called the "Middle Passage," was intolerable.

Some captains packed the slaves so close together they could barely move.

When the Africans were taken on deck for exercise, some tried to escape. Rebels were tortured or killed.

"Troublemakers, or those driven mad by their capture, were cut into pieces and hung from the mast, or beaten slowly to death to quiet the others," Opala says.

On the 10-week voyage, 13 captives died, most of them children.

The crew members threw their bodies in the ocean at night.

Such deaths were not unusual, says Opala. Captains and investors expected a certain number of Africans -- 15 percent -- to die; they factored the deaths into the cost of doing business. "The real horror was not that they were mistreated," says Opala, "but that the slave traders treated them as perishables."

Two million Africans died during the Middle Passage. A historian would later remark that, if the Atlantic were to dry up, it would reveal a scattered pathway of human bones, marking the various routes of the traders.

Says Opala: "It was mass murder in the name of commerce."

IN CHARLESTON, S.C., the slave trader Henry Laurens fretted.

He wrote letters -- sometimes two a day -- urging traders to visit other ports.

A junior partner in the firm Austin & Laurens, the 30-year-old Laurens had already made plenty of money by exporting lumber, rum and indigo, and importing slaves. Between 1735 and 1740, Charleston -- or Charles Town -- imported 12,589 African slaves.

After the colony's start, South Carolinians were producing so much rice that they paid their taxes with it. Slaves were needed to dig ditches and turn swamps into rice paddies. The planters preferred Africans from the Rice and Windward Coasts, where the villagers had been growing and harvesting rice for hundreds of years.

But in 1756, the market slumped. Freight and insurance costs were up, and profits were down. Carolina's rice growers could find few buyers for their crop, and they worried that England and France would soon go to war. Meanwhile, too many slave ships had glutted the market.

"Our planters are become very slack all at once," Laurens noted.

Five days before Godfrey's arrival, Laurens urged the Vernons in a letter to send Godfrey elsewhere. "Everything would be against him was he now to come here."

It was too late. Godfrey arrived on June 17.

Like other Africans coming into the port, Godfrey's slaves had to spend 10 days to three weeks in a brick "pest house" in Charleston harbor, five miles from the shore.

Worried about malaria, yellow fever and other diseases, the city had erected the Lazaretto, or plague hospital, on Sullivan's Island. The sick stayed in the 16-by-30-foot house until they recovered, or died.

Alexander Gardner, a port physician, reported frequently on the health conditions aboard incoming slave galleys. Their holds, he said, were filled with "Filth, putrid Air, and putrid Dysenteries . . . it is a wonder any escape with Life."

In letters, Laurens called Godfrey's captives a "wretched cargo." But he told a different story in an advertisement in the Gazette.

"Just imported in the Hare Capt. Caleb Godfrey, directly from Sierra-Leon, a Cargo of Likely and Healthy SLAVES, to be sold upon easy Terms."

The sale went poorly. Growers called the slaves "refuse" and were angry at having traveled 80 to 90 miles. By July 5, Austin & Laurens had been able to sell only 42 Africans. "God knows what we shall do with those that remain," Laurens wrote. "They are a most scabby flock," suffering from a contagious skin disease, sore eyes and infirmity.

Godfrey had other problems, too. Three slaves died while awaiting sale. His crew accused him of rough treatment, threatened him with legal action and finally abandoned him in Charleston.

"What I have is But in poor order having a Passage of almost Ten Weeks and the Slaves has rec'd Damage a Laying . . . I thought by my Purchase I Should have made you a good Voyage but fear the Low markit and Mortality Shall miss of my Expectation . . . " Godfrey wrote the Vernons.

ON JUNE 30, 1756, RICE GROWER Elias Ball Jr. bought the little girl and four other children for 460 pounds.

Mild-mannered, in his mid-40s, he owned two plantations, Comingtee and Kensington, both on the Cooper River, north of Charleston.

He slept on a hand-carved mahogany bed. He sent his boys to local academies run by European teachers, where they studied mathematics and rhetoric. The girls learned French and how to sew and dance.

Ball gave the children English names, Peter, Brutus and Harry. . . . He called the little girl Priscilla and marked her age in his ledger as 10.

Priscilla lived for another 55 years as a slave on the Commingtee plantation, where Africans cut pine trees, cleared land and dug irrigation ditches in the swamps.

Priscilla took a mate, Jeffrey. She had 10 children. She died in 1811 and was buried in a clearing on the plantation, near the Cooper River.

Her grave cannot be found. But a record of her life -- her purchase, her children and her death -- survived in the Ball family's slave lists, ledgers and receipts.

Tomorrow: Discovery