The draft makes all the difference. The Iraq war is a remote war to most Americans. People have extremely strong feelings about it, but in few cases does it touch them personally. Professor Andrew Bacevich, a former Army officer, told me that the war involves 0.5 per cent of the citizenry, which is one reason that support was high at the outset, and also one reason that it’s sinking fast. The public isn’t invested in it; the Administration hasn’t invested the public.

Togo RPCV George Packer writes “The Home Front” about the death, in Iraq, of a twenty-two-year-old private named Kurt Frosheiser, the effect of Kurt’s death on his father, Chris, and the broader issues that death raises about the war

Sons and Soldiers

Issue of 2005-07-04

Posted 2005-06-27

This week in the magazine, in “The Home Front,” George Packer writes about the death, in Iraq, of a twenty-two-year-old private named Kurt Frosheiser, the effect of Kurt’s death on his father, Chris, and the broader issues that death raises about the war. Here, with Ben Greenman, Packer discusses the article and the war.

BEN GREENMAN: What were the circumstances of Kurt Frosheiser’s death?

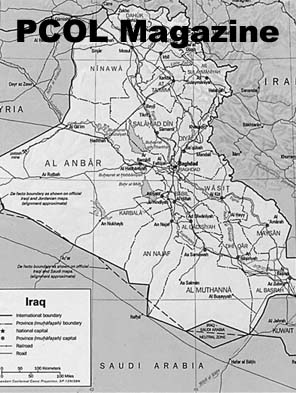

GEORGE PACKER: Kurt was killed by a shrapnel fragment from a roadside bomb while riding in a convoy in Baghdad on the night of November 8, 2003. A different angle—a little higher, a little lower—and he might have lived. As his father said by his grave, “Random thing.”

The focus of the article shifts from the front line to the home front, and it ends up focussing more on Kurt Frosheiser’s father, Chris, and how he dealt with his loss. How did you come to be acquainted with Chris, and with the story in general?

Just after his son’s death, Chris read my first New Yorker piece on Iraq, which included the story of Captain John Prior, who was in Kurt’s battalion. Chris wrote me a letter a couple of months later, which arrived when I was back in Iraq. Upon my return, we started an e-mail correspondence that continues to this day. I think Chris was impressed by John Prior, consoled somewhat that Kurt had been serving with such men when he died, and simply wanted to reach out, to learn as much as he could. We soon learned that we shared many common ideas and feelings about the war. I realized that I wanted to write about Chris and his family, partly because the experience of military families is such a central part of any war, and partly because I enjoyed our correspondence so much and admired his willingness to search and question without false or easy comfort.

Kurt expressed doubts about American success in Iraq in his letters to his father. Was his death caused in part by the unpreparedness of American troop? There’s a passing implication that it could have been prevented if he were in a different kind of vehicle.

The Humvee in which Kurt was killed was not armored, and there was no protective glass to stop the shrapnel fragment. This lapse was largely the result of the fact that the Pentagon anticipated withdrawing all but thirty thousand troops by the fall of 2003 and refused to acknowledge that the war hadn’t ended with the fall of Baghdad—that a second, deadlier guerrilla war had begun around the same time. Of course, war means death and tragedy, inevitably, including deaths as freakish as Kurt’s. What Chris Frosheiser asks himself over and over is whether military and civilian leaders kept up their end of the bargain with the soldiers by planning wisely and providing them with everything they needed. Chris has been very slow to place blame. He has wanted, as he said, to avoid bitterness, to keep faith with his son, and to believe that our leaders know what they’re doing. Eventually, though, he began to hold George W. Bush, Donald Rumsfeld, and others responsible, to a certain degree, for the lack of preparedness that contributed to Kurt’s death.

There is tension in your piece between Chris, a lifelong Democrat, who begins to question the American rationale for war more aggressively after his son’s death, and Kurt’s mother, Jeanie, who had become an evangelical Christian and told her local newspaper, “It’s an honor to give my son to preserve our way of life.” To what degree are they emblematic of the national divide in opinion?

Chris is restless and relentless in his search for answers, including in books of history and policy. I never spoke with Jeanie, but I gather that she regarded the war as a case of the forces of good against the forces of evil. There are many Americans who share her world view, and they are probably a disproportionate fraction of military families. I would guess that many more Americans, including military families, are becoming increasingly critical of the war effort. Blind faith is one thing; a desire to believe that democratic leaders are competent and honest is perhaps more understandable. Chris Frosheiser is disenchanted with partisans on both sides. To him, Iraq is too important for partisanship. In a sense, he’s the victim of an extremely polarized political moment in our history.

What range of opinions did you find among those in the military?

Among soldiers, I met a handful who see the war in what Chris Frosheiser called apocalyptic terms—but very few. I met others who, though not wearing their religion on their sleeve, spoke in critical or even disparaging terms about Islam, more out of frustration and exhaustion after months in Iraq than as a result of any deeper view. But one extremely worrying trend of the Iraq war is its transformation, in the eyes of some people in this country and many more in Iraq, into a religious war. The recent revelations about proselytizing at the Air Force Academy could be part of this trend. I once interviewed a Marine colonel who expressed serious concern that the officer corps of the armed forces has become increasingly evangelical. He thought that this ran the risk of skewing the war on terrorism in the direction of a war between faiths.

Chris Frosheiser became obsessed with finding meaning in his son’s death. Is this common among parents of soldiers who have died?

I think that Chris Frosheiser is an unusual, even remarkable, man. He has embarked on a quest, in books, conversations, and internal reflections, to understand the war as widely and deeply as possible, so that he can have, as he said, some peace of mind and heart about the reasons for his son’s death. He separates the nobility of Kurt’s service and death, about which Chris has no doubt, from the larger issues of whether the war was worth fighting, about which he has many doubts. This ability to hold competing, even conflicting, thoughts in his mind, while remaining genuinely open to the hardest questions, is extraordinary. I’ve more than once wished that the war’s leaders were more like Chris.

What are the generational issues raised here? Chris was an Army reservist during Vietnam and avoided combat; Kurt was a gung-ho volunteer who seemed to find his father too soft a personality. Would this war have faced more organized public opposition a generation ago?

Probably so. The draft makes all the difference. The Iraq war is a remote war to most Americans. People have extremely strong feelings about it, but in few cases does it touch them personally. Professor Andrew Bacevich, a former Army officer, told me that the war involves 0.5 per cent of the citizenry, which is one reason that support was high at the outset, and also one reason that it’s sinking fast. The public isn’t invested in it; the Administration hasn’t invested the public. Between Chris’s generation and Kurt’s, between Vietnam and Iraq, there’s also been a change in the attitude toward the military. Very few people today feel or show the kind of hostility to soldiers and uniforms that was all too common during Vietnam. Most Americans genuinely admire those in service. But, especially at the level of élite opinion, the war and the military remain abstract, distant things.

How much of the lack of momentum in the antiwar movement has to do with the Bush Administration’s skill at manipulating various mass media (talk radio, TV news, etc.)?

There was a growing antiwar movement before the invasion of Iraq; it involved millions of Americans. Once the war began, it quietly folded its tent, because most of those who had been protesting couldn’t bring themselves to say, “Turn around, go back!” Once the war became a fact, opinion consolidated around it, though millions of Americans remained opposed, without taking to the streets. Two years later, popular opinion has started to turn against the original decision to go to war, and is increasingly skeptical about its continuation. Perhaps the Administration’s relentless message discipline, and Congress’s failure to provide oversight, have kept the opposition in check. That is no longer working. In fact, the Administration’s conduct of the domestic side of the war makes it all the more likely that widespread worry and skepticism will quickly turn into a groundswell of opposition. We won’t, though, see mass demonstrations in the streets, I don’t think. That belonged to a different moment in history.

One of the reasons you give for the primarily rhetorical nature of the opposition concerns the growth of the Internet—people who have something to say can now say it fairly easily on blogs. To what degree has this undermined other forms of protest? What are the other factors?

Since the nineteen-sixties, Americans mainly on the left have had a certain image of opposition: hundreds of thousands of people in the streets. I don’t think it can be repeated, at least not automatically. That was a youth movement brought about by various conditions—the baby boom, the draft, the civil-rights struggle—that don’t exist today. The Internet seemed to be a brilliant new organizing tool in the months before the war (the fast-growing group Moveon.org is one example), but it doesn’t create the image that the media needs of mass opposition. So arguments against the war have been fragmentary and diffuse, like the Internet itself. Blogging is perhaps the main form of political expression in our day. It has its advantages—it has opened up public debate to everyone with a computer and a modem—but I’ve also seen it skew debate toward the rhetorical extremes, and toward a kind of self-referentiality. But I don’t think that if there were no Internet and no blogs we would see massive protests or other conspicuous kinds of opposition.

Much of your article grapples with the rationale given for the war by the Administration. How secretive is Bush’s government? Does this Administration insist upon an unprecedented degree of control of the symbols and images connected to the war, or has that always been part of waging war?

My political memory goes back to Nixon, and I don’t know of a more secretive Administration than Bush’s, with the possible exception of Nixon’s. We still don’t know when and why Bush decided to go to war in Iraq. It’s the “Rashomon” of wars: everyone’s view of the Administration’s rationale is different. In my experience as a reporter, as well as a citizen, the Administration has an absolute fixation on keeping information out of the public eye. In Iraq, I found it far easier to speak with soldiers at all levels who were under their own command structure than with civilian officials who were answerable to the White House. A request under the Freedom of Information Act that I made to the State Department, for a classified prewar document that poses no security risk at all, remains unanswered after a year and a half—which is a violation of the spirit of the law. Of course, every government wants to control public opinion and the flow of information, especially during wartime. Woodrow Wilson enacted the Espionage Act during the First World War to stifle critical views. Lyndon Johnson became famous for the credibility gap during Vietnam. With this Administration, especially given the Republicans’ hold on Congress, control has been raised to a level of technical perfection. But the war in Iraq is not affected by symbols and images in this country, and sooner or later that gap becomes a danger to the war effort and the public’s tolerance for it.

We hear a fair number of stories of parents of dead soldiers who come to feel resentful of the government. Is this simply a matter of grief, or is it a response to specific policies and attitudes of the Bush government?

Every war produces grief and resentment, and every war, even popular ones, in one way or another, pits the young who fight it against the government that sends them to fight. This Administration has increased that tension by withholding information as a matter of reflex and principle, refusing to engage in an honest debate or hold anyone accountable for failure, and failing to deal with the reality of Iraq in such a way that the soldiers there have what they need.

Many people, both in your article and elsewhere, have argued that private doubt and anguish have no place in public policy. In your opinion, does this argument hold water?

Not really. Ultimately, decisions about war in a democracy are going to be accountable to private feelings. The anguish of a mother or father who’s lost a child in Iraq can’t determine public policy. (Bill Clinton’s foreign policy suffered from the sense that he was mortally afraid of any casualties in any of the interventions in the nineteen-nineties.) But, when public policy becomes completely detached from private feelings in wartime, an Administration runs the risk of losing support very quickly.

In your piece, a number of young soldiers react to Kurt’s death with an increased awareness of the risks of Bush’s war policy. Right-wing commentators like to argue that this awareness can lead to decreased morale, which in turn can lead to a less effective fighting force. Is there some truth to this argument? What would Chris Frosheiser say about the need to keep troops invested in their objectives?

Morale in Iraq is not threatened by criticism of the war effort at home. It’s threatened by the soldiers’ own confusion over their mission and their sense that the military and the Administration might not be supporting them in every way possible. It’s also threatened by the nature of the war, which is shadowy, uncertain, and completely out of synch with the kind of war that the armed forces train for. Anyway, it’s impossible to shield soldiers from the debates going on here. The same debates are going on among them. I don’t think morale is dangerously low, but it will improve if or when things in Iraq improve.

What, ultimately, is the answer to Chris Frosheiser’s central question? What is the meaning of his son’s death? And, if it was not given to serve the objectives that were initially communicated to the American people, was it, in some sense, given in vain?

I can’t answer that question. Chris Frosheiser, insofar as I understand him, hasn’t answered it yet, either. He has, though, come to a certain resolution in his own mind: he can separate the meaning and value of Kurt’s life and death from the meaning and value of the war. He can feel some sense of peace that his son died honorably in service to his country without forcing himself to believe that the Administration held up its end of the bargain. In his first e-mail to me, back in April, 2004, Chris wondered aloud whether Kurt and the President took their oaths with equal seriousness. Since then, his pride in Kurt has remained intact.