Teaching and Learning in Turkmenistan by RPCV by John P. McCall

Teaching and Learning in Turkmenistan

reprinted from Knox Alumnus · April 1998

by John P. McCall Excerpts from a talk to the Caxton Club, September 25, 1997.

Almost four years ago, Mrs. McCall and I went on a great adventure. We volunteered to serve in the Peace Corps teaching English and were assigned to the former Soviet Republic of Turkmenia, now Turkmenistan. We arrived in the capital city of Ashgabat in October 1993, as part of the first Peace Corps team in Turkmenistan. Peace Corps groups had aleady been sent to the neighboring republics of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Kirghistan.

When we arrived, 32 Americans, we doubled the population of native English speakers in the country. That included European Community people from England and Ireland there on a variety of programs, the American ambassador and his staff, plus Peace Corps administrators. After three months of orientation, we were out among the people, paid our living allowance not in U.S. dollars or Russian rubles but in manat, the local currency.

We were truly in another world. We stood out in every way, and everything around us seemed different. One of the standard lines from the Peace Corps was, "Blend in." Impossible: as soon as we appeared on the street people knew these strange folks... If I were on public transit, crowded and mashed together with others, I would know if there were other Peace Corps volunteers on the bus, because I could hear them. Loud, free-speaking Americans. And you could see them blocks away, moving loosely and freely.

The food we had during Peace Corps training--people told us it was fine. It was either rice or pasta, in a stew juice, with a dollop of brown beef--or "meat," I should say. We found out later it might be camel or something else. But no one became sick from it.

The Turkish toilet was a surprise at first, but we came to realize that a clean Turkish toilet was to be treated with a great deal of respect. In fact, once we became accustomed to our environment, part of the game of life was knowing where to find a bathroom. From the time we woke in the morning, we had to have it in our minds that we were going to be within reasonable distance of one we could trust. Otherwise, we were in deep trouble.

We were ready for desert heat. Turkmenistan is a desert country, resembling our Southwest: 120° in the shade from June through August. I had a thermometer I rejoiced in using, putting it outside and seeing it get up to close to 130°F and then taking it back before it broke. We were ready for that. But, during our first weeks in the country, the temperature went down to 50, then to 40°; it went to 30°, and we had snow. In fact, we had snow every day from Thanksgiving until December 3rd. It was miserable. Cold and wet, and, of course, nothing was heated. The cement buildings seemed designed to hold onto cold in winter and heat in summer. Discomforts were all around us. Heat finally went on when the government decreed it should, and right after that the weather got better. We had no colder time than those first weeks in November and December of 1993.

There were all sorts of traps to catch the innocent. Potholes. You know an American pothole--child's play. Real potholes take a whole vehicle. That's the way to measure a pothole. And along the roads, the sidewalks and the buildings, there were rebars--reinforced steel or iron rods--sticking out ready to trip you, or catch your skin, or tear your garment. There was mud or dust and manholes without covers--those were the most interesting traps. Before our group of volunteers went off to our different assignments, we talked about who would be the first to fall down a manhole. You'd think it would have happened at night, but the incident that I was party to happened in broad daylight. A friend was taking us to her place for a birthday party and suddenly disappeared. She grabbed onto the sides, fortunately, and came away with only a few scrapes and a terrible scare.

In time, we became used to the sheep and camels grazing the garbage piles, but we never became used to the burning of garbage piles--the smells were so pervasive.

In winter, particularly, it was a good day if two or three of these things happened at the same time: there was running water; the electricity was on for our little fridge and the hot-plate units; public transportation was operating; and the telephones somewhere were working. Sometimes all four actually functioned.

Food shopping was a constant drain on the nervous system. We were used to seeing films of Soviet people in line for food, but we actually didn't see many lines, except at bread stores and when fresh fruit would come to market and be sold off the backs of trucks.

There were, however, long periods of time when there was no ration meat, no eggs or no wine. No compote or juice or jam, no cheese or butter, in the end, shopping became an art form. Whenever we would leave in the morning for work, we would each carry four or five plastic bags, so that if we chanced to find something for sale, we'd be ready. We were always hoping and watching.

Fortunately, we were spared dealing with the collapsed former Soviet health system. We had our own medical officer, a nurse-practitioner, thank God. We were one of the few Peace Corps units in the world that had its own medical person. If anything serious happened--volunteers were on a plane and out of the country. "Anything serious" included chipped teeth from rocks in the rice. Every volunteer with a serious problem was shipped back to Washington, D.C.

For the most part, too, we were spared the very worst effects of a command economy. We had no idea what a command economy is, until we experienced it. Simply, it means that the president (or dictator) decides what the economy is going to be at any time, irrespective of any reality. Hyperinflation might occur over the weekend. The value of what we had in our pockets could be cut by 10, 20 or 30% overnight. It meant that Westerners wanting to do business in this part of the world either had to deal in dollars "up front" or risk everything they had.

We never dealt in dollars ourselves. By dealing in manat we showed that we were living with the average Turkmen. At times, when the economy was terrible, those volunteers who were living on their own, buying and preparing their own food, were under great stress .

To give you some idea of the inflation we experienced: in November 1993, two manat equaled $1 U.S.; in December 1995, 3600 manat equaled $1 U.S. Moreover, the bribe to enter the university's English Department was $3,000 U.S. when we arrived. When we left, it was $10,000. It took time for us to learn such things, but after six months students started to be straight with us. No one would actually say, "I got into the university because my mother or father has a high place in the government," but that would be a primary reason for admission. The second reason would be business influence. Next, the sons and daughters of lower officials and their relatives. And there were actually a few students who had scholarships. For the most part, however, people were paying U.S. dollars, which were then distributed throughout the administrative system. Among other things, these payments almost guaranteed one a degree. If you entered the university in September 1993, you would graduate in June 1997. No problem. If you got into academic trouble, you'd be tested and re-tested and tested again, until the professor finally said either, 'I give up" or "Give me some dollars and all this will be taken care of."

After five or six months in Turkmenistan, we became survival people. We knew that every day would have its ups and downs--not bad days and good days, but bad minutes and good minutes. Our lives had a kind of a rhythm. We became seasoned troops, so to speak: we had the diseases of the area and lived a life that others lived through.

We learned to cope and adjust. ...

Well, what in the Lord's name were the good things in this environment? What provided the motivation, the strength and the purpose for what we were doing?

First, we learned how to celebrate in Turkmen style. We went to weddings; we became specialists in weddings. The first was out in the country, more than an hour's drive over God-knows-what-kind-of road. It was a village affair: several hundred people in the open air, music playing, dancing, food and drinks. It started at 5 or 6 in the afternoon and went on until 11 or 12. It was drizzling and damp, slippery in the mud, but through it all people were celebrating, eating and drinking, and dancing Turkmen style.., and later American style.

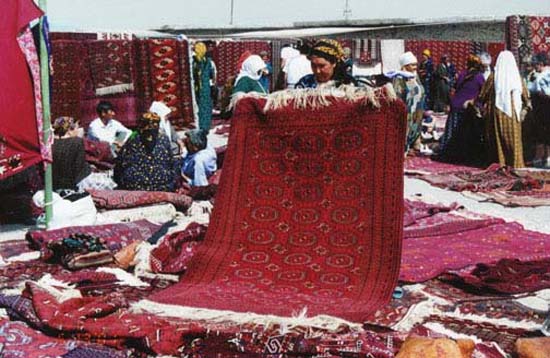

At people's homes, the parties were opulent. Family parties or group parties. We might come into a room and find two long carpets on which food was laid out--cold chicken, fish, three or four different kinds of salad, fruit and bread; soda pop, fruit juice, cognac, wine, vodka and champagne. Where did all this come from? Then later, the hot food--shashlik and plov--and desserts, and tea.

There were religious feasts, there were national holidays, parties in the public parks, parties at homes and offices, and we went to as many as we could. Our last New Year's party began at five in the afternoon, at the house of a colleague, strictly a family affair. There were three children and a niece, the mother and father. It lasted until 1 or 2 a.m. (They wanted us to stay over for the night.) Between courses came the social activities: we danced; we sang; we told stories and toasted good things; we listened to the daughter play the piano; we went outside and walked around for awhile, and ended with cakes, cookies and tea...

We also learned to do without, and sometimes that came hard. Increasingly we became patient. We never wanted to become really patient, because that's part of being an American, being able to assert your impatience. We never became docile. But we learned, as those of you have lived abroad have learned, to live with the situation. My favorite example is the weekly trip to the laundry. Now, most of our laundry was done by Mary-Bernice in the bathtub in our apartment. But there were some things that simply had to be taken out, particularly my shirts, because dressing up for the university was an absolute necessity. On Tuesday mornings, before going to class, I would go to the laundry, which was a couple of miles down the road from us. I'd try for public transportation, but couldn't always count on it. On Thursdays before class, I'd repeat the trip and pick up the laundry.

Fine... except sometimes the laundry would be closed. The washing machines would be broken or there'd be no water, so I would have to go back home with the laundry and start over again on Wednesday. And the same with the pick-up: "No, we're closed," or, "No, we weren't able to do it," or "Come back tomorrow," Now, at first one could get really mad about such things, but after awhile.., it's a pain in the neck but, "O.K., I'll see you tomorrow."

There were a host of things we found satisfaction in--first of all, in the people we met. Particularly, the honest, the honorable and the courageous people we met. Many, many of them women in positions of minor official responsibility, who found ways of getting things done. My Turkmen teaching colleague was one of them. I was so proud of her when she failed a student (the first in anyone's memory) and stood up to the complaints against her. The screaming mother, the pressuring dean, the unhelpful colleagues. The dean, who had been to the States asked me, "Now, don't you have a grade where the student passes but doesn't get a passing grade?" I said, "Yes, but I've gone through my notes on this examination and, by my count, the student had an 'H': about 20% correct."

There was a newspaper reporter who interviewed me, who might have been in jail on a better day, but he had retired successfully and wanted only special assignments. He wondered what the Peace Corps was and why we were doing this teaching, and what we got for it? His assumption was that there had to be something in it for us. I explained what I could and then quoted President Kennedy, "Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country." At once, he put his hand to his head: "My God, that's wonderful! We have to learn that." And he kept repeating , "We have to learn that."

Then there were the women who cleaned the streets, hardworking, mostly elderly. Turkmen women, wrapped in clothes to protect themselves from the dust and dirt and heat of the day. The students at the university showed great respect for these women. One even wrote a little poem in English about a woman who swept the sidewalks in the city park, concluding, "And at the end of the day she went home with a clean heart."

We were especially proud of our students and many of our colleagues. At the university, English was taught the way my generation was taught Greek and Latin: memory, drill, repeat, repeat, repeat; don't think, just do it. Keep your' mouth closed and listen. Repeat after me. Write when I tell you to write, make sounds when I tell you to make sounds, and make them accurately. The Turkmen faculty knew we Americans taught in a crazy way, and they knew we taught in an inadequate language (American English) with terrible sounds. But finally, many of them came to recognize that somehow the students that we were teaching performed better.

I had one group of students all the time that we were in Turkmenistan. I taught others as well but kept this one class throughout. When they and the other English language classes did some short plays for a Christmas audience, I was awed by my students. They were so at ease with their English. They were colloquial, they were funny, they were glib, they were laughing. Some students might have been academically more correct, but they were stiff as boards, repeating beautifully what they were told to repeat. On the other hand, here were my would-be theater students, putting on a show in a foreign language.

In addition, the students who won English language awards and who scored best in TOEFL [the Test of English as a Foreign Language] in order to study in the United States were ours. And these were first- and second-year students, not third and fourth. They were good students, but they also had the benefit of the kind of language instruction that we Americans learned from the British, the French and other Europeans, and that we were now able to take to Central Asia.

The chair of our department was an ethnic Russian, a temporary department head waiting for a Turkmen academic to take over. But at the end of our time there, at a meeting where we sat and listened, she said to her colleagues, "Yes, we are going to change the curriculum; I know you won't like it. And we are going to use the American books that the McCalls got for us from the U.S. Information Agency. This means we can't use the books we've used for years."

Well, as students and teachers, you know what her words meant: we can't teach the way we were taught or teach the way we've been teaching! Mary-Berenice and I had thought that this change would or could take place five or six years after we had left, but it happened in a few months through the leadership of one woman and then others ready to say, "O.K. we'll try."

Would we have agreed to a change like that back here? We would have had a committee established to report back in 12 months or 24 months. As a professor at an American college, I wouldn't have put up with it!

We were proud, too, of the students and staff who supported a Model United Nations program. Mary-Berenice and another volunteer created the first Model U.N. in Central Asia. It was a marvel and it took courage. Courage on the part of a few people in the Turkmen foreign ministry; courage on the part of the Peace Corps volunteers because they were under scrutiny by both the Turkmen government, afraid of what the subject matter might be, and the U.S. government. · . for the same reason. What were the students going to talk about? Freedom? Yes. They were going to talk about health programs, ecological issues and women's rights. They would hear guest speakers like the U.N. representative to Turkmenistan in English. They studied in English; they wrote their research papers in English. They conducted their meetings in English, including their Model U.N. meeting at the end of the course.

In the final analysis, we sometimes wondered, What did we teach in Turkmenistan? We taught English, but Mary-Berenice said, "No, that isn't what I taught. I taught critical thinking."

I would say, yes, that's true, but we also taught freedom. Freedom, American style: being secure and confident to think and express yourself. It was quite something to go into a classroom where everybody knew that the rule of the game was to keep quiet and not to say what you think. In fact make-believe that you didn't think at all. Imagine being in such a classroom and asking a student, "What did you think about what we just read?" At first, no answer, only a glare.

It was not that these students didn't know what they thought. They would speak freely at home and in the safety of their friends, but never in public. And certainly never at the university or in the schools. So imagine our delight, at the end of a year, when two of our students got into an argument in class. Or imagine one day looking out the window of my classroom at the Kopet Dagh mountains south of Ashgabat, and there is smog in the air. So I begin teaching the word "smog," smoke and fog and so on. "O.K., does everyone understand?" And I say to Silash, one of my favorite students, "Now, you understand what smog means?"

And she says, "Yes, Mr. McCall, but that is not smog, that is a dirty window. That window has never been cleaned since this building was built in 1946." To have someone answer you back in Turkmenistan was just wonderful. I felt like inviting all my students to say "No" to me, to say, "You've got it wrong" or "I don't think so." Such things were really important to us.

After we came home, we were often asked if we really enjoyed Turkmenistan? That was mind-boggling at first. Of course not! Enjoy? That wasn't it at all. Did we find satisfaction in it? Yes, great satisfaction. We would not have missed it for the world. And, would we go back? Not a chance.

Only one volunteer in our group left of his own accord. That was miraculous for a Peace Corps unit. Unless there were a serious health or family problem, people stayed. Yet no one has returned; no one has wanted to return. We made many dear friends, but the former Soviet Union is very depressing.

Of course, in time it will change. Students are coming from Turkmenistan to the United States. And they are enjoying it. They are finding problems here, but they will take home from America part of what we tried to bring them--a sense of their own worth, their own dignity and their capacity to be free and thoughtful people. Also to be part of a larger world, as well as of their families and their clans. And there is, as you would expect, great satisfaction in that.

John P. McCall was President of Knox College from 1982 to 1993. He is a retired Peace Corps volunteer and currently a volunteer staff member at Xavier University of Louisiana.